It was a great delight this last Sunday evening to share in the Archbishop of Brisbane's commissioning of our diocesan Angligreen committee for this year. This was the first time such a commissioning has occurred and, taking place in St John's Cathedral, was a beautiful and prayerful symbol of Anglican intent to place ecological concerns at the heart of our life, just as it is in the very centre and being of God. The Dean, Peter Catt, gave an excellent address to complement this meaning of the occasion (very much 'belonging with, belonging to, belonging in'): click here for a copy.

1 Comment

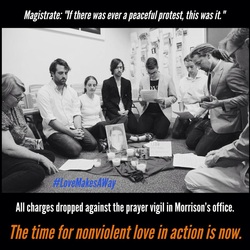

A few weeks ago a small group of Christian friends shared a prayer vigil to pray for humanity in Australia's handling of asylum seekers. Taking place in the Federal Minister, Scott Morrison's office they were arrested, but yesterday the case was dismissed. What a beautiful way to approach Palm Sunday! Like Jesus' humble protest on the first Palm Sunday against the power and oppression of his own day, we are recalled to the power of nonviolent love. Of course, the policies remain in place, but there is another notch in the transforming of our consciousness as well as political and media publicity. May the Spirit continue to move in all kinds of ways to change our outlooks and actions. Jarod McKenna puts it well in how 'Easter Made Me Do It'.  When I reflect on this Sunday's Gospel in the context of recent events, I have to say that I start thinking of the plight of asylum seekers and of our current national policies towards them. This, for me, is not so much about politics but above all about our sense of compassion. When Jesus heard about Lazarus and thought about him, we are told he wept. When we open our ears and eyes to the appalling plight of the world’s asylum seekers, should we not be weeping too? - weeping, crying out and working for new life? Instead, I fear that we, as a nation, are in danger of simply reinforcing the door to the asylum seekers’ tomb. For it is a place of great fear and horror and death, and we would rather not smell the stench, never mind do much about it. Instead of opening up the path to new life for asylum seekers, we are therefore in danger of simply building new tombs for them, in places like PNG and Cambodia. With appropriate prudence, might we not do better to heed the words of Moses and Jesus: unbind them, and let them go!? For the problem with shutting up the stench of life, our fear and death, is that, in doing so, we also block off new life. Whether as individuals or as a nation, we deny ourselves the possibility of true resurrection. We may shut our fears away but they are still there. Our hearts know this and they will shrivel until we face them. We become lesser people, and a lesser nation, than we might be, and we undermine our compassion. May God set us free. In the name of the Holy One who sought asylum with his family in a foreign land: in the name of Jesus who raised Lazarus from the dead, Amen.  Is cross-community meditation an idea whose time has come? Does our world badly need it to transform its dysfunctionality and stress and to deepen our shared awareness and connectedness? - such were questions, answered in the affirmative, which emerged from our wonderful 'Silence for Peace' community meditation workshop in Toowoomba today. It was a personal joy to help facilitate this and to help add a vital new level to our work of 'building a model city of peace and harmony.' People of different traditions have been practicing meditation as part of the wisdom of the ages. Until recently however we have done this in our separate 'boxes'. Indeed, within western Christianity, the ancient traditions of Christian meditation were largely lost, until renewed lately, not least by Fr John Main and the World Community of Christian Meditation (WCCM). Undoubtedly a major force was the rise of eastern religions and philosophies in the west, especially from the 1960s. In secularised forms, meditation has also now spread to all kinds of hitherto unlikely places, including boardrooms and prisons. Meanwhile, multi-faith and multi-cultural relationships have prospered. A natural step therefore seems to bring people of different backgrounds together to share and strengthen our individual commitments and underpin our wider work for peace with shared inner peace. From a Christian perspective, cross-community meditation awareness and practice has certainly been a major feature of recent and continuing WCCM work. As Fr Laurence Freeman has written (in a paper 'The Contemplative Parish'): Two great challenges offer the parish and the Church as a whole an opportunity for regeneration: the rediscovery and reappropriation of its contemplative tradition as a living practice among all its members and the encounter in deep dialogue with other faiths. These two are intimately linked... Inter-religious dialogue (like inter-denominational ecumenism) thrives in a contemplative environment. Unity is then seen as an already existing reality rather than as something to be created. Friendship and humour replace competitiveness and pomposity. Such an outlook lies behind significant WCCM initiatives, including the development of cross-community meditation encounters across the world. For our part in Toowoomba today, we began with an Aboriginal Acknowledgement of Country (by Aunty Gwen Currie) and reflection on 'dadirri' and the ancient 'Aboriginal Gift' of contemplative peace in our land. We then shared in brief introductions to meditation from different perspectives including: Pure Land Buddhist (from Venerable Wu Ping); Christian/WCCM (Jo Anderson, from St James' Church, Toowoomba); Quaker silence (Pam Tooth); and a wider community perspective (from Viki Thondley, a holistic therapist and owner of Mind, Body, Food, specialising in mindset, lifestyle, stress and eating disorders). Their input was interspersed by short periods of silence and introductions to meditative practice, including a memorable walking meditation together in the Pure Land Meditation Hall. Hosted as we were so graciously at the Pure Land Learning College, we then concluded with a pleasant vegetarian meal together. Key common themes were the deep connectedness of mind, body and spirit which is (re)discovered in meditation and the consequent deep re-connecting with self, others, land and universe and the deepest reality of life itself. When I first met with others to plan this event we did not expect anything as many as the number who came: a sign that indeed this is a powerful need and joy in our hectic and distracted world. We look forward therefore to the regular 'Silence for Peace' cross-community group which will now begin to meet next week (at TRAMS (Toowoomba Refugee & Migrant SErvices), 123 Neil Street), and to future developments and encouragement of inner peace and connection within our wider community (among individuals, schools, and other groups) as a whole.  'Are preaching and doctrine really barriers to peace and multi-faith harmony?' Awkward questions are uncomfortable to ask, even in congenial gatherings. Yet some are also necessary. For every group has places where it prefers not to go, despite its ultimate health depending on doing so. This is true for multi-faith groups, as it is for church and other groups. For multi-faith groups too can sometimes begin to build walls they do not realise they are creating. Last Saturday's otherwise excellent Interfaith Forum in Toowoomba was a case in point. I felt awkward demurring at the groups' discussion feedback (see photo above) but I felt something needed to be said. For, among many very helpful and constructive ideas for moving forward, up came the old chestnuts that 'we should not preach' and that 'we should avoid doctrine and just share love'. Well, yes, and no... The damage done, over the centuries, to human relationships by bad or misdirected preaching and by mishapen doctrinal assertion and conflict is incalculable. Today, hopefully, most of us are ever more sensitive to of the pain and disharmony which can be caused. There are times and places, ways and styles, which are more or less appropriate. In some areas, such as in what ecumenical and inter-religious scholars call 'the dialogue of life' and the 'dialogue of action', preaching and doctrine may be particularly important to play down. Within multi-faith and many secular settings, there are also people who have been so hurt by bad religion that we need to give priority to gentleness and restraint in communication of our own personal inspirations. Yet without doctrine we lose both the dynamism which leads to genuine unity and harmony and also the will and openness to truth upon which such unity and harmony depends. 'Love unites, doctrine divides' is certainly a popular contemporary slogan. It is even heard sometimes within otherwise informed ecumenical circles. Partly, the aversion is a case of language. Today, both preaching and doctrine smack to many of olde worlde, as well as troubling, times. It is possible indeed that such words may one day be beyond recall, in the same way that the word dogma (understood as 'non-negotiable, incontrovertible' doctrine) is pretty much taboo. Yet they are so much part of our human religious fabric, especially within Christian circles, that rehabilitation would be a better option. After all, the reality is that everyone has doctrines. Buddhists, and some others, call them 'teachings' but they are the same thing. 'Love unites, doctrine divides' is indeed (a somewhat amorphous) one of these for some. Apart from pointing out that a significant part of my life has been, and is still, given over to preaching, my own sense is that disdain for preaching is based on bad experience or misconception. After all, one of the greatest peacemakers of my lifetime was Martin Luther King Jnr, who was a preacher in word, deed, and essential personality. You could no more take the preacher out of him than you could take his passion for peace and justice, love and harmony. For these were all one, grounded in his love and experience of God in Jesus Christ. So to reject preaching, in the best sense of the word, in all circumstances, is to reject one of the distinctive charisms of Christianity (and also, to some extent, those of Islam and some other faiths). It would certainly do little to endear multi-faith discussion and relationships to many Christians for whom this is part of their lifeblood, not as a weapon towards others but as a means of grace for all. What matters is how we preach and teach. Graciously, on Saturday, this concern was heard by others. For at the heart of our journeying with others of other faith, and none, is respect for the inner integrity of one another and what shapes us for good. Doctrine itself is a vital matter for ecumenical and inter-religious as well as confessional and intra-religious life. For it is a tool which can be used to help us grow together, as well as being a potential, and well proven, weapon of division. As with other things in religion, it is a case of how it is used. Is it a barrier to protect us against others or a freeing pathway upon to which walk? Is it used for the glory of God and for human self and mutual understanding or for self or group aggrandisement? Is it a means to learn and grow, written on our hearts and in our souls rather than in proscriptions of others? Ultimately every doctrine is, even at its very best, but a symbol of eternal love. We must always be wary therefore of overstepping the mark in our own doctrinal exploration and affirmation. Yet, even when we fail to comprehend them, the greatest doctrines of faith, as genuine symbols of God's love, can be for us means of grace and revelation. As such, they cannot simply be laid aside in multi-faith relationship. They are too important for that. As the ecumenical journey has shown, 'Life and Work' concerns must proceed hand in hand with 'Faith and Order' dialogue. Sometimes love is best expressed just in presence, care and service. Intertwined and underlying however are always our understandings of love. It is a matter of our human intellectual responsibility to complement and deepen our feelings of well-being towards others. If we never wrestle with what helps and what hinders we will fail to grow in love and we will hold back our gifts of, albeit glimpsed, understanding from one another. For as G. K. Chesterton (in What's Wrong with the World?) once said: 'creeds are always in collision. Believers bump into each other; whereas bigots keep out of each others’ way.' |

AuthorJo Inkpin is an Anglican priest serving as Minister of Pitt St Uniting Church in Sydney, a trans woman, theologian & justice activist. These are some of my reflections on life, spirit, and the search for peace, justice & sustainable creation. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed