One of the reasons I was happy to be part of the trans faith film Faithfully Me (premiered tonight) was film maker Rachel Lane's track record of assisting in sharing the voices of other typically marginalised groups, not least Aboriginal ones. For one of the challenging invitations of our time is nurturing intersectional relationships which enable justice and fullness of life for all - for too many, otherwise very necessary, 'identity' struggles are weakened by restricted commitments and groups which tend only to include their own kind. Over the years, many Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander leaders have pointed me to a better way, supporting the needs and hopes of others even, at a cost, when their own are so outstanding. We 'progressive' white folk haven't always reciprocated well. Here, below, is a little excerpt from Secret & Sacred, an example of Rachel's earlier work, a glimpse of the deep wisdom of the Badjatala people (whitefella Hervey Bay & Fraser (K'Gari) Island region), but a snippet of the neglected ancient but very much living wisdom of this land. With particular thanks to Glenn Loughrey and Dianne Langham, Canon Bruce Boase, and Aunty Rose Elu for their continuing personal inspiration to me in sharing solidarity - and to other friends, like Tony Robertson and Johnny Valkyrie, who respond so beautifully and model how the liberation of any of us is entwined with the liberation of us all. This is so absolutely contrary to today's right-wing 'religious freedom' push, and central to authentic catholic faith, as so powerfully expressed in John Donne's Meditation 17: for the bells which toll, toll for us all. The chimes of freedom - human rights and flourishing - are indivisible - so let's ring out our different bells in a harmony of joy :-)

0 Comments

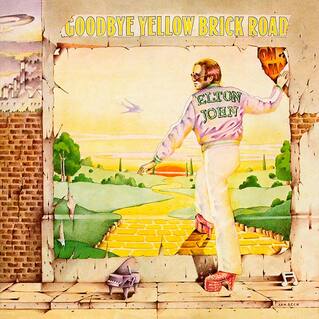

I speak today as both a proud member of our LGBTIQA+ community, and also as a dedicated person of faith, indeed as an Anglican priest. I do so, because people like me are typically erased, our lives and voices ignored. Yet we queer people of faith do exist! - and we are increasingly seeking to be visible. For our very existence gives lie to the monstrous misuse of religion for political ends. We suffer particularly profoundly from religious discrimination. We do not want religious exemptions which hurt us and others, and betray the heart of who we are. We also know that the majority of our fellow Australians of faith agree with us, as we saw in that dreadful postal survey. So we’ve tried to lobby, spoken to Government inquiries, sought to be part of desperately needed change. Yet, as queer people of faith, our rights to religious expression are seldom recognised...  I remember vividly the day Elton John came to my little town. It was like a breath of life from another planet. For, let's face it, in Market Rasen, it was akin to a hundred big events in one, but with unprecedented glitter. Indeed, in the 19th century, Charles Dickens said that you could fire a cannon down the main street at 10 pm on a Saturday evening and you wouldn't hit anyone. Not much has changed, even now. Sadly Elton didn't stop to say hello to the little kid I was. He still left an impact though, just as his songs were an integral part of the soundtrack of my youth. For Elton was in Rasen for a wedding of Bernie Taupin, his close friend and lyricist. Bernie was, in part, 'one of us' - born a Lincolnshire 'yella belly', spending part of his own upbringing locally, and attending Market Rasen Secondary Modern School. Some of Bernie's lyrics reflect this, including the song 'Saturday NIght's Alright for Fighting' (partly an anthem to the experience of the Aston Arms and other places of Market Rasen 'entertainment'). Linking up with Elton was Bernie's way out, and maybe, somewhere in my consciousness, their story was a promise of an alternative pathway for myself and my childhood friends. Was stepping on 'the Yellow Brick Road' possible for us too? The concluding tour of Elton's career, and the release of the film Rocketman brings this back. There's much I owe to this influence - particularly in learning, so slowly and painfully, to sing 'Your Song' as my own song...  Who would have thought, in Australia in 2019, that, thanks to the insistent Tweets of a rugby player, hell would gain such attention? Hellish is certainly the result for those of us in the rainbow community. Particularly since the recent Federal election, we have been subjected to a deliberate right-wing campaign of aggression and hate, with fresh destructive impacts on our mental health and well being. This is a powerful expression of the vicious distortions of so much of today's media, and the apparent eagerness of some 'religious' groups to promote, or be used by, repulsive reaction in the name of religion. It is also a vivid reminder, both of how theological concepts can have real life consequences, including in the political sphere, and also of the need for a religious, as well as much broader, response by LGBTIQA+ people of faith. For religious-inflicted pain is indeed rife and horrendous among LGBTIQA+ people. Anger at religion as a whole is therefore, as a huge understatement, more than understandable. More moderate 'straight' religious people urgently need to recognise this and join the rainbow community as much more effective allies, with a commitment to genuine listening, deep repentance for religious-based shaming and violence, and powerful commitments to assisting in change. Yet, as it uses religion, we are also unlikely to defeat the hideous distortion that is right-wing 'religious freedom' without better theological scrutiny and the use of religious resources by LGBTIQA+ people of faith, affirmed by other parts of the rainbow community. In this, one key feature is indeed to reclaim the very idea of hell as a theological impulse towards justice for the oppressed, connected with the vision of 'a new heaven and earth' of peace and love, not as punishment of 'the other' by the rich and powerful. For God, if that world is to have reality at all, needs proclaiming as the ultimate source of transforming love in generous diversity, not as a mean tyrant picking on the marginalised. If hell is to have any real meaning, other than as a description of actual lived pain today, then it must be as a reminder that, in some ultimate sense (to use Billy Bragg's words): 'there will be a reckoning for the peddlers of hate... and a reckoning too for the politicians who left us to this fate'...  Where do you find feminist religious inspiration when you need it? Sometimes the answer is hidden in plain sight. So it was for me at school. For I was involved with a number of social transformations at my local secondary school, including being part of the first year of the historic admission of females. This not only seemed a self-evident justice to me, but it was also a personal saving grace. Indeed, in my final two years, I was part of otherwise all-female classes for most of my subjects, bar one other male assigned student (in religious studies). Also, to the initial chagrin of some, our 19th century grammar school (founded in 1863 out of the medieval charity created by Thomas De Aston, a 13th century monk) two years later finally fully joined the modern world as a 'comprehensive' school: merging with the local 'secondary modern' school, whose pupils were traditionally divided from us by the selective examination known as the '11 plus'. At which point school 'houses' suddenly appeared, under the names of the well-known local Lincolnshire worthies Tennyson and Wesley; the explorers (Joseph) Banks and (Matthew) Flinders (actually much better known in Australia than in their homeland); the fearsome Hereward (famed indigenous resistance fighter against the Normans), and, more mysteriously, (Anne) Askew. Happily I was placed in her house, but who was this, to us, unknown woman? Sadly, I never really found out then. On asking, apart from guessing that she was the 'token' woman in the list, we were told she was martyred at the Reformation. 'Great', said most of the boys: 'not only do we not get to be associated with a fighter like Hereward, or at least an intrepid explorer like Flinders, but we get landed with a woman, and one whose claim to fame is being slaughtered.' Even the girls had sympathy with the latter affirmation. Yet, had we been given a richer explanation, we might have had a very different viewpoint. For, of all the Lincolnshire icons, it is arguable that Anne Askew was the greatest of all. She was not just a type of freedom fighter (like Hereward), an intrepid adventurer of the new (like Flinders and Banks), a poet (like Tennyson), or a model of renewing spirituality and freedom (like (the) Wesley(s)). She was all these in one, and she did it all as a woman to boot...  In the heat of current political issues, is it possible to find a healing ethic of religious freedom? Might a fresh look at Christian tradition help us with this? The ideological use of notions of 'religious freedom' is certainly hardly new. Judaeo-Christian history is riddled with it and their consequences. Jesus himself was famously condemned, according to John 's Gospel (11.50). since it was argued that it was better for one person to die than for the nation to be destroyed (allegedly). Other faith expressions and Christian 'heretics' have met comparable fates. Meanwhile, in many places, Jews and Christians have experienced, and continue to experience, harassment, persecution, and even outright destruction. Yet the Jewish and Christian traditions are also founded on expansive ideas of liberty, grounded in the very being of God in God-self, and on liberative myths and symbols such as Exodus from slavery, return from Exile, deliverance from sin and evil, and the in-breaking and embodiment of God's reign of justice, peace and love. These have empowered, and continue, to empower people to achieve freedom across the world. Not for nothing then did Martin Luther call his seminal work 'On Christian Freedom'. Its use highlights three typical trajectories western society has explored in relation to 'religious freedom'. Its central message however points us deeper...  If Samuel Johnson were around today he might well feel that religion, rather than patriotism, is the last refuge of the scoundrel. It certainly seems to be an excuse, or self-justification, for all kinds of bad behaviour, as well as a source of strength and inspiration to holiness in others. Not least this is the case in regard to some leading Christian approaches to LGBTI+ people and their vigorous intent on backlash. At times horribly distorting reality, they even hijack 'religious freedom' into its opposite - i.e religious privilege - thereby further diminishing religion's positive features and making life very difficult for those very many Christians who believe and act differently. Indeed, when it comes to the current contentious battle over 'religious freedom', as both a transgender person and a Christian, I consequently frequently find part of who I am dismissed by one contending group or another. When, instead, will we recognise that the real problem are the scoundrels? Just as Samuel Johnson was not attacking patriotism as such, only a false kind of patriotism, so we do well to call out those with 'bad faith', whilst finding a fresh consensus among those genuinely seeking balance of conscience and liberty, whether we are secular or not. .. Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall.

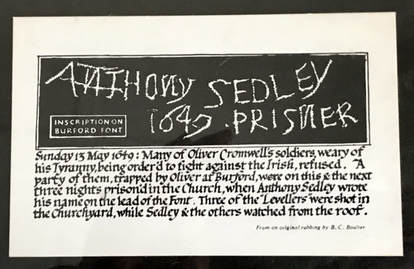

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall. All the Pope’s horses and all the Pope’s men (and women), couldn’t put Humpty together again. For good and ill, the era we know as the Reformation has hugely shaped us. It involved immense fragmentation: both a breaking down and a breaking open. Like Humpty Dumpty, that which went before had ‘a great fall’ and could not be put together again as it had been. Especially within Christian life, it has thus bequeathed so many features we simply take for granted. Some have lasting value. Others are much more questionable. This includes the very existence of different Christian traditions, in what, from the 19th century, we have termed denominations. This was not, of course, an intended outcome. Indeed, it would have seemed anathema to any Reformer, as well as to the Church of Rome. Yet it is part of our Reformation inheritance. So what do we make of this, for God’s continuing mission? What is worth keeping? How might we move on together? This reflection is not a traditional potted history. Nor does it seek to draw us into comparisons of our different Christian traditions, never mind reassemble past dynamics and rhetoric. Instead, it outlines briefly both vital differences and also important similarities between that age and our own. In doing so, it identifies a number of negative features which often mar our churches and world. It also suggests a number of positive features which can heal and take us forward. Hopefully, in the contemporary spirit of ‘receptive ecumenism’, these may then provide a basis for assessing which Reformation gifts we will own together and which we will leave behind. What else, we might then ask, do we need for our journey onwards today?...  From my early childhood, I have always been engaged in exploring what liberty means. I grew up fascinated by history for that reason and it is not for nothing that the pictures over my office desk resonate with some of the mightiest of English struggles for liberty: a copy of the Magna Carta, photographs and records of female suffragists, and, most poignantly of all, a facsimile of the Leveller Anthony Sedley's scrawled protest on the font of Burford Church (see picture to the right). Such epic battles, mixed in as they often were with religious identity and aspiration, both challenge and inspire. They are in parts a record of gruesome hurts but also witness to the Christ-like 'courage to be', to re-imagine, and to 'turn the world upside down' Imagine then my frequent puzzlement and dismay, when some people, in comfortable places, speak about religious liberty as merely the right to hold and publicise curious opinions and practices or to protect privilege. Of course I would not wish to deny others the first of those things. Yet liberty is so much more...  As we let go of one year and begin another, it is good to give thanks for all that has been and to open ourselves with fresh hope and compassion to the future. The two things are connected. My final visit in Berlin this year for example was a way of paying tribute both to past inspiration and to its continuing living 'subversive memory'. For in the Friedrichsfelde Central Cemetery are the graves of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, among others commemorated at this Memorial to the Socialists. Other parts of the cemetery also house the graves of creative people, including the amazing artist Kathe Kollwitz. In some ways it is a sad place, not only as cemeteries typically can be, but also because of the failure of much of the vision and hard work of those buried there. Yet as the main commemorative stone has it Die Toten mahnen uns (The dead remind us), at their best, prompting us to renewing life and love. My politics have never been quite those of Liebknecht and Luxemburg, but I have always admired their commitment to a better world, sacrificial solidarity with the poor and outcast, intelligence and vision. To lay a flower on each of their graves was thus for me to express a debt of gratitude and to pledge with others to renew their work in a new way. My guess is that, in Rosa Luxemburg's case for sure, if they had not been murdered by the Freikorps in Berlin in 1919, their work would have been betrayed by others, including those indeed like one or two of the East German communist party apparatchiks buried alongside them. For being of Polish birth and Jewish extraction, and a feminist socialist with a physical disability and a brilliant independent mind, Rosa was always an uncomfortable figure to so many. Her most famous words sum this up and remain a powerful challenge and inspiration, whatever group(s) we belong to: Freedom only for the supporters of the government, only for the members of a party – however numerous they may be – is no freedom at all. Freedom is always the freedom of the dissenter. Not because of the fanaticism of "justice", but rather because all that is instructive, wholesome, and purifying in political freedom depends on this essential characteristic, and its effects cease to work when "freedom" becomes a privilege. For those words alone my pilgrimage would have been worthwhile, but there is much more. For to me, Rosa stands for many more, living and dead, who continue to believe in, inspire, and work, for another kind of world, however we imagine what Christians like me call 'the kingdom of God'. And so, for the coming year, in the words of the anarchist poet Pietro Gori, in Primo Maggio, written in 1890: Green May of humankind, Give your courage and your faith to our hearts. Give flowers to the rebels who failed Their sight fixed upon the break of dawn, To the bold rebel who fights and works To the far-seeing poet who sings and dies. |

AuthorJo Inkpin is an Anglican priest serving as Minister of Pitt St Uniting Church in Sydney, a trans woman, theologian & justice activist. These are some of my reflections on life, spirit, and the search for peace, justice & sustainable creation. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed