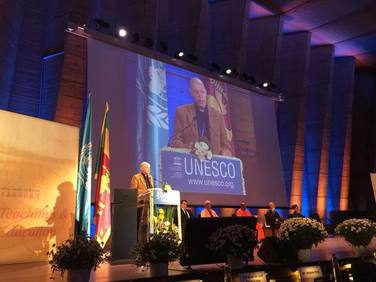

my address to the Vesak Conference at UNESCO, Paris, 28 May 2015 as part of the Toowoomba 'Model City of Peace and Harmony' presentation Let me begin with some words from a great poet and priest in my Anglican tradition: No one is an island entire of itself; every one is a piece of the continent, a part of the main; … any one's death diminishes me, because I am involved in humankind. And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee. This wisdom is still powerful today, even though John Donne himself lived through the violent crises of his own age 400 years ago. For they are words for us all. Whilst they embody Christian understanding about human-divine solidarity, they are also reflected in other wisdom traditions, not least Buddhism. For no one can be an island today: no person, no religion, no country. What happens, for example, here in Paris, affects the rest of the world. In response to their own trials, many French people have said Je suis Charlie Hebdo. At it its best, that is another way of saying what John Donne said long ago. For whatever bell tolls - in Sri Lanka, USA, Israel-Palestine, Syria, Iraq, Nigeria, the Congo, Toowoomba, or wherever – it tolls for us all...

0 Comments

my short address from the inter-religious panel of which I was a part at the UNESCO forum last week... Amitofu - salaam alaikum - shalom - g'day... I would like to share a special prayer - one which has been of great value to churches across the world, who together, through bodies such as the World Council of Churches, have sought intentionally, throughout this 21st century, to address violence and its causes. There are 4 elements to this prayer. These, I believe, help to sum up and focus Christian understandings of peacemaking: 4 elements to which, of course, we need to add another, namely, repentance (understood as saying sorry for our own parts in the violence of the world - and what others have done in our name: the name of our religion, or our country, or our ethnic or other group.) This is presupposed, for without repentance - without a profound change of heart - we cannot be free. The 4 elements of my prayer today help us seek this repentance or change of heart, as they are elements which are similarly deeply grounded in the Christian tradition but which are also accessible to all, to people of other faiths and none - and what we have heard earlier from Madagascar, for example has reflected that. The four key elements of this change of heart are: Firstly, Truth - because without truth we can never deal with things properly. Now of course Truth can be uncomfortable to face up to - like the truth about the violence inflicted in Australia in the past on our Indigenous peoples, or the truth of facing up to the violence of what has caused war and violence elsewhere, and continues to do so. Yet without truth there can be no reconciliation and no real healing - we are always likely to be violent again. As Jesus said - 'the truth will set you free'. Secondly, Justice - for without Justice there can be no real peace - as the biblical tradition has it, peace and justice belong intimately together: as the Psalmist puts it (Psalm 85.10) justice and peace must kiss one another for live to triumph. Or, as Pope Francis has reminded us, "without a solution to the problems of (today's refugees and) the (global) poor, we cannot resolve the problems of the world.' Thirdly, Compassion - for Compassion is, for Christians, the heart of God, and embodied in Jesus Christ. Until we have a heart for one another - until we start to share one heart, as some Indigenous peoples say, then we will always be broken people and a broken world. Until then there is a part of our own heart missing. We have to seek grace to cultivate kindness and mercy and their power to transform us and our world. Fourthly, Courage - for ourage is required to take risks for peace, justice and compassion. This is the courage of Jesus even to risk death in the hope of a better world and in the assurance that nothing can ever destroy the ultimate reality of life - the love of God - which can transform all that evil throws against it. For making peace comes at a cost but it is the path to renewal, or, as Christians put it, redemption. All of these things - truth, justice, compassion and courage - are crucial as part of our education for peace and a repentant, or transformed, heart and world. So let me therefore share this prayer of blessing: May God bless us with discomfort at easy answers, half-truths, superficial relationships, so that we will live deep within our hearts. May God bless us with anger at injustice, oppression and exploitation of people, so that we will work for justice, equity and peace. May God bless us with tears to shed for those who suffer from pain, rejection, starvation and war, so that we will reach out our hands to comfort them and change their pain to joy. And may God bless us with the foolishness to think that we can make a difference in the world, so that we will do the things which others tell us cannot be done. In Jesus Name, Amen. Love this creative, and appropriately fresh democratic, way of marking Magna Carta...  For several years I have had a copy of Magna Carta on my living room wall. An odd thing this may seem to many. It seemed a waste however to have it rolled up in a cylinder and it is a reminder to me, both of my personal history and origins and also of the continuing challenges to seek and nurture liberty. For I grew up, for most of my childhood and youth, near Lincoln, whose Cathedral owns one of the originals from 2015, now located in a permanent exhibition in Lincoln Castle. I also treasure a visit a few years ago to Runnymede, the site of the Magna Carta agreement, close by to where my sister currently lives. Above all, Magna Carta touches on so many aspects both of my historical interests and political concerns. In this 800th anniversary year of Magna Carta, it was therefore wonderful yesterday to be able to visit the Magna Carta: Law, Liberty, Legacy exhibition in the British Library. What most, pleasantly, surprised me in the exhibition were the series of historical documents, books and other artefacts from across the centuries. These were great to see, as well as refreshment to the European part of my soul which, much as I love Australia, sometimes struggles with the lack of appreciation down under of the highly diverse layers of history. Perhaps Europeans can sometimes themselves be trapped in such layers, and ignore the much more than human immensities of life, and such gifts as those of the oldest continuous civilisation on Earth, found in Australia. Yet, for me at least, to delve back into my own inheritance of history is to feel a renewed sense of intimate connection, wonder and empowerment. The Magna Carta exhibition, as its subtitle suggests, seeks to place Magna Carta in the great traditions - I would say always uncertain struggles - of law and liberty, and their legacy, particularly in Anglo-Saxon shaped countries. Lines of influence are drawn across time: including to English resistance to 17th century tyranny, 18th and 19th century radicalism, American affirmations of liberties, and 20th century declarations of rights (including by the UN and Nelson Mandela). Rather than being a legal instrument of tight principles, it is perhaps best viewed as a continually revered tool against oppression and a potent inspiration to 'maintain the rage'. Unlike other approaches, such as French and Russian, this Anglo-Saxon pathway to liberty looks not so much to radical logic or abstract ideals as to the precedents and pragmatic practices of the past, albeit often mythopoeic visions and creations out of the contexts of later times. Only three articles of Magna Carta are still UK statutes but it still has the power to shape our past and future. One remaining article is the first in Magna Carta: affirming the liberty of the English Church in the face of monarchical (or, by implication, other) domination. This reflects the work of the then Archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langton, a key force for reconciliation and (limited) justice in 1215. Significantly however, the then Pope disagreed, dismissing Magna Carta to the dustbin of history in his papal bull which followed. Ironically Sir Thomas More did not agree later, appealing to Magna Carta against king and for the papacy. Perhaps Christian leaders, in our own age, would do well to renew that spirit of Magna Carta, whilst seeing its insistence on liberty as something not for a special few but for all, whoever and whatever we are. The barons, like the then king and Pope, of 1215 would have been horrified to see their ideas of liberty so extended. Blind or forgetful to the inspirations and horrors of history though we may often be, we 21st century people really do not have the luxury. |

AuthorJo Inkpin is an Anglican priest serving as Minister of Pitt St Uniting Church in Sydney, a trans woman, theologian & justice activist. These are some of my reflections on life, spirit, and the search for peace, justice & sustainable creation. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed