I learned today of the death of the Venerable Master Chin Kung, one of the world’s spiritual leaders (in the Pure Land Buddhist tradition) and someone who enlarged my life in many ways, particularly in the wonderful relationships he helped nurture among so many different people in Toowoomba and many different countries across the world. The picture above is from one of the international journeys some of us in the Toowoomba City Goodwill committee took with the Venerable Master - here in Singapore, en route home from one of the UNESCO peace conferences he arranged and we attended in Paris. So much else has been nurtured however through the peace initiatives the Venerable Master nurtured through the Pure Land community he inspired - including, not least, in Toowoomba. The Venerable Master, like Hans Kung, believed that people of faith could be forces for peace and good in our world, especially where they worked together, with people of all cultures, drawing on the best of all faith and human wisdom, because ultimately all is drawn from the same source and we walk best together. Indeed, without faiths working together, we lack and become harsh. He encouraged faith leaders always, daily, to share what we have which can build up, as he did daily in his teaching, whatever else he was doing and wherever he was in the world. He believed so much in the power of loving kindness, attentiveness, making connections (across traditions, cultures, centuries, and any distinctions) and he helped us in that work. His generosity also included being a partner in our Toowoomba City Labyrinth installation at St Luke’s Toowoomba - a continuing symbol of multicultural and multi faith walking together. The Venerable Master’s legacy will, I know, live on and flourish - in the lives of all who knew him, especially his Pure Land communities who feel his loss so deeply at this time. My own love and prayers go out to my dear friends in Toowoomba in this, with thanksgiving.

1 Comment

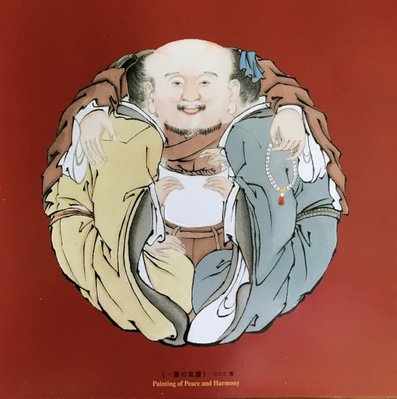

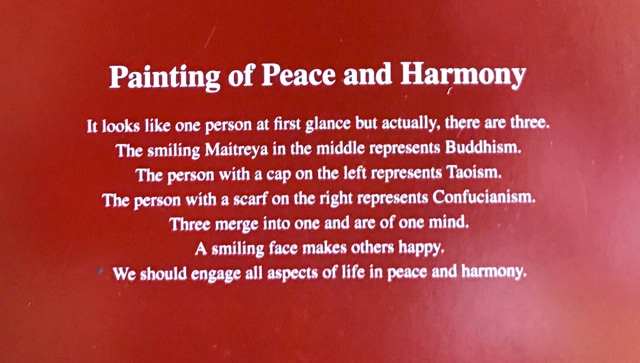

In the midst of handover work for our impending move, it was lovely today to have a visit from my dear friends Mr Haniff and Meiling, updating me on the UNESCO partnerships we have been working on with others in Toowoomba and bringing me a beautiful new year's greeting card from the Venerable Master Chin Kung. The front of the card has this interesting picture. What do you see in it? An explanation is given below.... It can be misinterpreted by those who see inter-religious dialogue as seeking some kind of mish-mash of philosophies. Yet I do not feel that this is that at all. Rather it is an expression of the deep understanding of the Venerable Chin Kung that all great pathways of wisdom can connect. Indeed that they connect most deeply when we walk together in peace and harmony. May this be a blessing for us all in 2017.  This morning a number of members of the Toowoomba Goodwill Committee met at St. Luke's to consider ways to strengthen our city wide work of peace and harmony in the face of violent events overseas. Several of us in Toowoomba have been to Paris in recent years to speak and work with UNESCO on peacemaking in our world. So there is a particular extra poignant sadness among us at the recent events in the French capital. Our hearts and prayers also however go out to those who have suffered similarly in Beirut and other places in recent days. All this reinforces our need to work more closely together for peace at all levels, to educate and address religious bigotry, and to extend a compassionate and informed welcome to refugees who are escaping from just the kind of horrors the media has reported. We join with the Taize Community in France in the following prayer: Eternal God, we want our thoughts and acts to be based on your presence which is the source of our hope. We entrust to you the victims of the attacks in Paris and in Beirut, and in so many other places and their families and friends as they mourn. With believers of all backgrounds we call upon your name and pray: may your peace come to our world.  my address to the Vesak Conference at UNESCO, Paris, 28 May 2015 as part of the Toowoomba 'Model City of Peace and Harmony' presentation Let me begin with some words from a great poet and priest in my Anglican tradition: No one is an island entire of itself; every one is a piece of the continent, a part of the main; … any one's death diminishes me, because I am involved in humankind. And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee. This wisdom is still powerful today, even though John Donne himself lived through the violent crises of his own age 400 years ago. For they are words for us all. Whilst they embody Christian understanding about human-divine solidarity, they are also reflected in other wisdom traditions, not least Buddhism. For no one can be an island today: no person, no religion, no country. What happens, for example, here in Paris, affects the rest of the world. In response to their own trials, many French people have said Je suis Charlie Hebdo. At it its best, that is another way of saying what John Donne said long ago. For whatever bell tolls - in Sri Lanka, USA, Israel-Palestine, Syria, Iraq, Nigeria, the Congo, Toowoomba, or wherever – it tolls for us all...  my short address from the inter-religious panel of which I was a part at the UNESCO forum last week... Amitofu - salaam alaikum - shalom - g'day... I would like to share a special prayer - one which has been of great value to churches across the world, who together, through bodies such as the World Council of Churches, have sought intentionally, throughout this 21st century, to address violence and its causes. There are 4 elements to this prayer. These, I believe, help to sum up and focus Christian understandings of peacemaking: 4 elements to which, of course, we need to add another, namely, repentance (understood as saying sorry for our own parts in the violence of the world - and what others have done in our name: the name of our religion, or our country, or our ethnic or other group.) This is presupposed, for without repentance - without a profound change of heart - we cannot be free. The 4 elements of my prayer today help us seek this repentance or change of heart, as they are elements which are similarly deeply grounded in the Christian tradition but which are also accessible to all, to people of other faiths and none - and what we have heard earlier from Madagascar, for example has reflected that. The four key elements of this change of heart are: Firstly, Truth - because without truth we can never deal with things properly. Now of course Truth can be uncomfortable to face up to - like the truth about the violence inflicted in Australia in the past on our Indigenous peoples, or the truth of facing up to the violence of what has caused war and violence elsewhere, and continues to do so. Yet without truth there can be no reconciliation and no real healing - we are always likely to be violent again. As Jesus said - 'the truth will set you free'. Secondly, Justice - for without Justice there can be no real peace - as the biblical tradition has it, peace and justice belong intimately together: as the Psalmist puts it (Psalm 85.10) justice and peace must kiss one another for live to triumph. Or, as Pope Francis has reminded us, "without a solution to the problems of (today's refugees and) the (global) poor, we cannot resolve the problems of the world.' Thirdly, Compassion - for Compassion is, for Christians, the heart of God, and embodied in Jesus Christ. Until we have a heart for one another - until we start to share one heart, as some Indigenous peoples say, then we will always be broken people and a broken world. Until then there is a part of our own heart missing. We have to seek grace to cultivate kindness and mercy and their power to transform us and our world. Fourthly, Courage - for ourage is required to take risks for peace, justice and compassion. This is the courage of Jesus even to risk death in the hope of a better world and in the assurance that nothing can ever destroy the ultimate reality of life - the love of God - which can transform all that evil throws against it. For making peace comes at a cost but it is the path to renewal, or, as Christians put it, redemption. All of these things - truth, justice, compassion and courage - are crucial as part of our education for peace and a repentant, or transformed, heart and world. So let me therefore share this prayer of blessing: May God bless us with discomfort at easy answers, half-truths, superficial relationships, so that we will live deep within our hearts. May God bless us with anger at injustice, oppression and exploitation of people, so that we will work for justice, equity and peace. May God bless us with tears to shed for those who suffer from pain, rejection, starvation and war, so that we will reach out our hands to comfort them and change their pain to joy. And may God bless us with the foolishness to think that we can make a difference in the world, so that we will do the things which others tell us cannot be done. In Jesus Name, Amen.  It is a delight to be in Europe in beautiful spring weather. It is not a very happy political 'European spring' though. All over Europe, on the brink of EU elections, uncertainty prevails and doubt is common about the 'European project' of community. For an expatriate European like myself, immersed in many historical memories, it is a troubling sight. Ironically, I am in Paris this week, speaking at UNESCO with Toowoomban friends about our 'Building a Model City of Peace and Harmony' initiative. My own particular theme is Co-operation: something from which so many Europeans seem to wish to stand back. Partly doubts about EU cooperation are understandable. The European dream seems rightly hollow to the millions who are unemployed, and to the poor and ethnic minorities struggling for recognition, for decent housing, work and living conditions. The EU can seem so distant to many, apparently overly bureaucratic and a feeble tool for more immediate concerns. Hence unhealthy right-wing parties have gained ground across the continent and even France, a founding co-pillar of the project, moves in the direction of British cynicism. How soon we forget though! This coming week (21-28 May) is 'La semaine sanglante' - or 'Bloody Week' - in Paris, the anniversary of the final episode of the Paris Commune of 1871 (see photo above: from the memorial in Pere Lachaise cemetery in paris where the last stand of the Communards was made). Recent historical examinations of death and burial records suggest that the actual week's death toll (probably around 7 000) was significantly lower than the more outrageous figures (of 20-30 000) which have long been touted, and which were used (by notable figures such as Lenin) as an example of the true barbarous heart of capitalist 'order'. Yet even such reduced figures are a staggering witness to the deeply bloody past violence of Europe, consequent on deep national, social and economic divides. The Paris Commune was a deeply ambiguous, but, historically, vitally symbolic, event. In one sense it was a magnificent act of faith and a living adventure of hope, created by some of the most wretched of people in the most wretched of circumstances. Karl Marx and others, then and since, have commended it for putting an abstract concept of freedom and justice into reality, however shortlived. Great contemporaries who lived through it, like Victor Hugo and Emile Zola, were also deeply moved by its genuine social idealism as well as shocked by its own internal violence, as well as the greater violence of its repression. What is sometimes forgotten however is that the Paris Commune arose out of the despair, anger and humiliation of the Franco-Prussian War. Indeed, the proclamation of Kaiser Wilhelm as Emperor even took place in the Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles in January 1871: a staggering affirmation of Prussian power at the heart of former French glory. Crushed by the rising, recently unified, German Empire, the Parisians refused however to accept the surrender made by their national leaders. Instead they proclaimed a new form of society in the Commune. It was thus a product of a century of such conflict and bloodshed all across Europe. Its legacy was also lasting. Among those caught up in the politics of the Commune was George Clemenceau, later so important in insisting on crippling reparations on Germany in 1918. One can but imagine the thoughts and feelings which flowed through him as he concluded the Treaty of Versailles, remembering the scenes and indignities of his youth. The outrages of the Commune's rise and fall, as an apotheosis of European divisions and violence, thus flowed right through to the second world war. The European Community project was an attempt to end it for ever. It still is. How soon we forget. The EU is hardly perfect but it requires development not destruction. Its doubters, sometimes for self-interest, are looking in the wrong direction. Recent studies continue to state the reality that social and economic division is a much more genuine and difficult challenge than any migration of peoples or cultures which they bear. In Britain, 1% of the population own as much as the poorest 55% and their wealth is increasing by 15% a year whilst others struggle. Such statistics are reflected elsewhere. Hardly any European today would wish to replicate the politics of the Paris Commune, yet perhaps its uncomfortable ideals have something to say to us, lest Europe descend further into uncooperative and unnecessary division and violence. Australia, still buoyed by comparative economic advantage, might take note too. |

AuthorJo Inkpin is an Anglican priest serving as Minister of Pitt St Uniting Church in Sydney, a trans woman, theologian & justice activist. These are some of my reflections on life, spirit, and the search for peace, justice & sustainable creation. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed