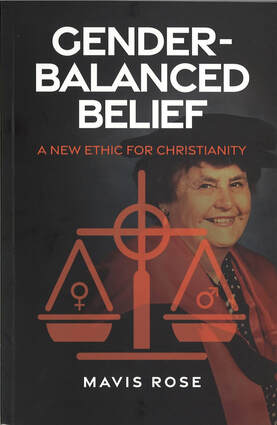

First of all, may I acknowledge the traditional owners of this land and all First Nations people in this area. I also give thanks for this cathedral, so important to me in my own journey in recent years, and all who have helped develop the unfolding work of Christian feminism which we highlight tonight. In introducing and commending Mavis’ book, I am reminded of a number of things from the first wave of Christian feminism, which was the subject of my Ph.D. One is a famous quotation from the northern English working-class leader Ada Nield Chew: women’s advance, she used to say, ‘’tis a long row to hoe.’ What we do today, as Mavis encouraged in her book, is part of a continuing journey. The South African writer Olive Schreiner put it strikingly in one of her essays, which drew heavily on biblical imagery, and helped her become the ‘muse’ of first-wave Christian feminists. One of the Anglican suffragettes, Lady Constance Lytton, referred to this in her autobiographical account of the sufferings of female campaigners in prison. We were encouraged each night in Holloway, she recalled, by readings of Schreiner’s work, not least the story ‘Making a Track’. An allegory of women’s, and others’, struggles for justice, this described a long trail of the bodies of insects stretching over a long distance. These learn, as Olive Schreiner put it. to ‘take off the shoes of dependence’, to clothe themselves in ‘the garment of Truth,’ and to use ‘the staff of Reason’ when they are lost and cannot find a way. Eventually the track of bodies reaches the banks of a river to cross into a more spacious land of freedom, fording the river with the costly solidarity of their bodies. On the other side, there is room for more authentic life and expression. ‘But what of those who did not make it?’, asks one of the characters in the story, ‘those who were swept away by the current or did not even build the bridge with their bodies?’ ‘What of that?’, comes the reply, ‘they make a track to the water’s edge’ and ‘over that bridge, which shall be built with our bodies… the entire human race will pass.’ Mavis was one of those great Brisbane women who helped form the bridge of women’s ordination, and stepped over. Yet, as the exhibition of Anglican women’s history in this cathedral affirms, she would not have been able to do so without others who had made the track to the water’s edge. Vitally, she also knew that stepping over the bridge was not enough. Much more was needed. Some of that has been in evidence in recent years, including the first female bishop in this diocese. Yet Mavis was clear that such landmarks are insufficient without a much greater transformation. This is what she calls us to in her book Gender Balance. It seeks, and embodies, not an end but an encouragement to travel on. Indeed, for me it is a particular delight to see it published, for it represents a key part of the track – after the ordination of women - that was so difficult, and which is so easily ignored. If we are to travel on further, into fuller life and freedom for all, we need to see the whole track and learn from it. This is what Mavis’ book helps provide. We are diminished without it. Understandably, after the first ordinations of women, the movement which brought them about lost steam. Partly this was because so many wonderful women poured their hearts, faith and lives into parish and other ministries hitherto denied them. This brought much fruit but came at a cost from which we are still, I think, recovering. As a lay woman who had helped lead MOW locally, Mavis saw that. Gender Balance thus represents her perceptions of what more is needed on the track. She perceives the insidiousness of patriarchy and clericalism. She asks us to go deeper, to reconsider symbols and language, relationships and support. She also reminds us of the bigger vision of Christian feminism, so much larger than ecclesial offices or church facing concerns. Lift your gaze, she continues to challenge us. Renew the pathway and the purpose your forebears marked out, at the cost of their bodies, lives and faith struggles. Mavis thus recalls us to the promise of the 21st century in which we live and to a better Faith in which to live it. She outlines how the continued undervaluing of women is a major feature of what she calls ‘Christianity’s Credibility Crisis’. Indeed, she shows how women and women’s experience is devalued in aspects of our Faith and how dissent is resisted by entrenched attitudes and structures. At the heart of this is what she calls ‘The Embodiment Problem’, even though women carry with them connections and resources which can bring new life. She affirms that women’s theology and spiritual experience can thus help to renew the expression and work of the gospel, providing health in so many other fields also. Gender Balance is not entirely complete as a vision of Christian feminism for today. For there are some new elements recently which have entered the journey, which can make us stumble or enrich us. Mavis does not really speak for example of the rise of sexual and gender diversity, which have made the track more complex and enlivening. She also wrote at a time before the full rise of recent phenomena of terrorism and anti-terrorism, and the resurgence of populism and authoritarianism in politics and religion. Yet, even in the face of such factors, Mavis reminds us in the book of other features which we have neglected. Not least, particularly at the end of this Week of Prayer for Christian Unity, is the value she rightly gives to solidarity and co-working across our denominational and national boundaries. She thus draws widely on the work of Catholic and other theologians, and on ecumenical connections, not least the inspiration that was the Ecumenical Decade of Churches in Solidarity with Women. What an idea that would be to see again! What a difference it makes when women and others make fresh linkages together, as the #MeToo movement and Marches for Justice have shown recently – the wider and deeper agenda of liberation is not lost, but renewed. I sadly only met Mavis in person once: when she came to my home, on the St Francis College site, to talk with some of our students and others about the ordination of women struggle, its legacy and learnings, and the need for the continuing journey. Yet I feel strongly that, if she were here today, she would be warmly encouraging us to take the next steps on the track – and this, she indeed does today through this book, distilling some of her lively insight, informed reading and personal wisdom, continuing to challenge us (as the self-confessed ‘Anglican spiritual guerilla’ she was) and willing us on. Do take up Mavis’ book, learn and inwardly digest, and, inspired by her spirit, and that of all who have gone before us and made the path to the water’s edge, build the next bridge and help others cross over. For like Mavis, we either help to make our own history, or are condemned to be victims of it.

0 Comments

Penny and I are feeling very blessed after renewing our marriage vows this week in St John's (Anglican) Cathedral in Brisbane - on our 35th wedding anniversary. We had intended to mark this occasion by beginning several months long leave overseas. COVID-19 put an end to that. However we felt powerfully drawn to mark this point in our lives, particularly after this year completing the main elements of my gender affirmation journey. It also gave us an opportunity to celebrate a 'queer' marriage which some of our co-religionists say is impossible (!) but which we believe is a lovely gift for the renewal both of marriage and also of human relationships with our wider creation. For, as I have written elsewhere (see here for example), a deeper wrestling with Judaeo-Christian tradition leads us into a much more profound and life-giving understanding of marriage and God's shalom...

Of all the chapels in all the world, the Mary Magdalene or Morning Chapel in Lincoln Cathedral lies deepest in my heart. At every key stage in my life, and before every major decision, I have prayed there, asking for support, affirmation, guidance, reassurance, or simply the receiving of joy or holding of pain. It is more than that Lincoln is a spiritual home, born of years of growing up nearby, and of participation in important events in the cathedral and of all kinds of things in the city (including, of course, of its special little football club at Sincil Bank, the other Lincoln 'spiritual' centre inscribed in my heart). Mary Magdalene and I go way back, as I have reflected elsewhere. She has been my sister, model, and inspiration in struggle, faith and new life, helping me to be transformed from silence, suppression and stigma (see further here, and here). Yet now I discover something I should have known long ago: that her name and spirit is attached not only to that special cathedral chapel, but it lies also beneath the cathedral itself. As such, she symbolises for me the foundational love beneath the types of 'Norman yoke' we have forced, or placed, upon ourselves...  It was a huge delight to be part of the launch of the Reconciliation Action Plan of the Anglican Church Southern Queensland (diocese of Brisbane) in St John's Cathedral Brisbane last Thursday. Together with a Welcome to Country, didgeridoo music, food, and audio-visual display of Reconciliation activities across the diocese, a particular highlight was also the performance of the Malu Kiai Mura Baui dance troupe and speeches from Archbishop Phillip Aspinall and our National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Anglican Council diocesan leaders Canon Bruce Boase and Aunty Rose Elu. Almost 200 people attended the event, including the most prominent lay and ordained Anglican leaders in the diocese, local elders and representatives of leading organisations such as Reconciliation Queensland.  The RAP Launch was the culmination of four years work of awareness and relationship building across the diocese and represents a significant step forward. Indeed the ACSQ RAP is highly unusual for the sheer scale of its geographical and organisational extent, covering both such a large area of Australia with so many different Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander peoples and involving every section of the diocese, including finance and service departments, as well as parishes, schools, St Francis College and Anglicare. May God bless all involved in making this next stage of shared commitment real in the days ahead. What does London's St Paul's Cathedral represent to others, I wonder? For Londoners it symbolises many things, not least indomitable survival. As a northerner with a love-hate relationship to the Great Wen of the English capital, my feelings are more complex but just as deep. St Paul's is not quite my people's cathedral - 'wor cathedral' of Durham and the beauty of Lincoln both have claims to that. Yet it is also the people's cathedral for me - a very different entity from the royal chapel of Westminster Abbey. It is also my cathedral in a very special sense, as the place of my ordination as priest. Set in the centre of a great world city St Paul's also speaks to me of a love and vistas which are uiniversal and ever outward looking. Its design is also open to the future and to reason. Even the tomb of Wellington is tamed by poets and progressive purposes. Sadly Dean Alan Webster, a beloved mentor, is long gone. Yet his spirit still speaks to me, with St Paul's, of a greater peace and a rich and genuine liberality which even now could perhaps enable London, Europe and the wider world. Today's bridge across the Thames links Donne with Shakespeare, making the point even more powerfully to me.

|

AuthorJo Inkpin is an Anglican priest serving as Minister of Pitt St Uniting Church in Sydney, a trans woman, theologian & justice activist. These are some of my reflections on life, spirit, and the search for peace, justice & sustainable creation. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed