Where do you find feminist religious inspiration when you need it? Sometimes the answer is hidden in plain sight. So it was for me at school. For I was involved with a number of social transformations at my local secondary school, including being part of the first year of the historic admission of females. This not only seemed a self-evident justice to me, but it was also a personal saving grace. Indeed, in my final two years, I was part of otherwise all-female classes for most of my subjects, bar one other male assigned student (in religious studies). Also, to the initial chagrin of some, our 19th century grammar school (founded in 1863 out of the medieval charity created by Thomas De Aston, a 13th century monk) two years later finally fully joined the modern world as a 'comprehensive' school: merging with the local 'secondary modern' school, whose pupils were traditionally divided from us by the selective examination known as the '11 plus'. At which point school 'houses' suddenly appeared, under the names of the well-known local Lincolnshire worthies Tennyson and Wesley; the explorers (Joseph) Banks and (Matthew) Flinders (actually much better known in Australia than in their homeland); the fearsome Hereward (famed indigenous resistance fighter against the Normans), and, more mysteriously, (Anne) Askew. Happily I was placed in her house, but who was this, to us, unknown woman? Sadly, I never really found out then. On asking, apart from guessing that she was the 'token' woman in the list, we were told she was martyred at the Reformation. 'Great', said most of the boys: 'not only do we not get to be associated with a fighter like Hereward, or at least an intrepid explorer like Flinders, but we get landed with a woman, and one whose claim to fame is being slaughtered.' Even the girls had sympathy with the latter affirmation. Yet, had we been given a richer explanation, we might have had a very different viewpoint. For, of all the Lincolnshire icons, it is arguable that Anne Askew was the greatest of all. She was not just a type of freedom fighter (like Hereward), an intrepid adventurer of the new (like Flinders and Banks), a poet (like Tennyson), or a model of renewing spirituality and freedom (like (the) Wesley(s)). She was all these in one, and she did it all as a woman to boot...

0 Comments

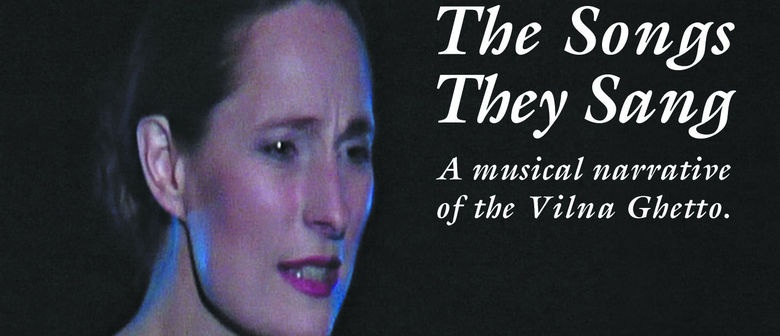

One of my favourite Billy Bragg songs is Handyman Blues (see below for a video version with leading British comics): a wonderful consolation to those of us who are deeply admiring of our fathers and others differently abled, but who are far more capable with words and images than nails and hardware. I was thinking of this a few weeks ago when I made a rare trip to Bunnings Warehouse as part of a family wedding and move preparations in Canberra. What would be the equivalent of Bunnings Warehouse, I wondered, for those of us cursed and blessed with Handyman Blues? Perhaps it would be a Poetry Pavilion? As it happens, this year's London Book Fair instituted a Poetry Pavilion for the first time to promote poetry more fully (see here for one poet's account). How encouraging! In my soul's eye however, a Poetry Pavilion version of Bunnings Warehouse would be far more dramatic and quirky. For a start, quite unlike Bunnings' admirable practicality, like a Celtic rune, nothing would be straight, never mind the aisles. All would be curves and squirls, wiggles and squiggles. In contrast to the predictable sausage sizzle at the door, food would be of all varieties, with sensational mixes of spices and scents, and delicious wines abounding Instead of tools and serviceable items, in curious corners and angular alcoves, each decked with fascinating fabrics, metaphors and motifs would be hiding, with songs titles and dance themes a plenty. Nor would a single uniform be in sight. Everything would be free but would cost all that the heart requires. A chance visit to the Balaclava area of Melbourne led me this week to pick up a flyer in a cafe for a deeply moving documentary (entitled 'The Songs They Sang') on the experiences of the Vilna (one Vilnius) ghetto. Negotiating my way to the delightful, and somewhat accurately named, Backlot Studios, I was variously challenged and inspired by the horrendous inhumanity, and the courage, hope, poetic and practical resistance of those had lived and died in that terrible time. I was also reminded how important it is to keep hope alive, even in the most desperate of circumstances, and to carry forward memory, so that light can continue to shine and triumph again in our world's persisting darkness. I was but one of a handful of people at the showing yesterday, and all but one other were older East European Australians. Yet the beautiful and poignant understated documentary, and accompanying CD of the songs from the ghetto, continue to share the story and lead to sanity for others too.

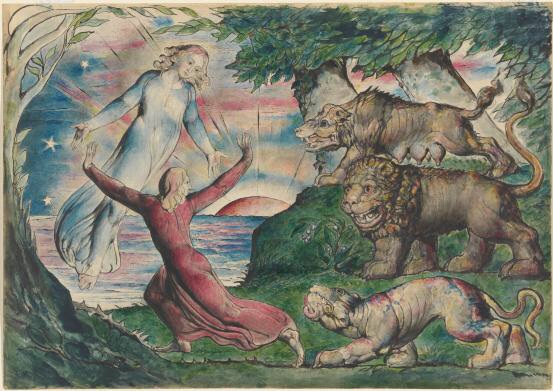

This work is timely, both for the Jewish community and for the wider global community as it endures further horrors of genocidal and ideological madness. As the last survivors of the Shoah dwindle, it is vital that their songs and stories are shared. A major theme of the documentary is indeed that of the third generation of ghetto survivors and it begins with a granddaughter returning to Israel for her grandfather's funeral. Like the Jewish children singing in Vilna today the ghetto songs, the affirmation of the later generations that 'we are here' is a powerful expression of hope and the reality of life surviving even abject and extraordinary death. For the experience that is related speaks both of what was and what is and will be. In the face of the ghetto's horror, and the daily encounter with death (close at hand or in the killing fields of the nearby Ponar forest), the Jewish community used theatre to keep the spirit alive. In this they were aided by remarkable people, such as Amroz Sutzkever. Probably the greatest Yiddish poet of the holocaust and one of the most outstanding poets of the whole 20th century, Sutzkever's words were both brilliant in their expression and amazingly strengthening amid the scarcely imagineable harrowing. Nor was he alone. One of the most powerful parts of the whole documentary is the song Mother, written by Chayele Posnanski after the murder of her mother. She herself also did not survive the war and this is the only legacy she left. Like Satzkever's work, the song acts as a means of transcendence, an affirmation of life in the midst of the almost unbearable grief of existence. Poetry is thus, like other arts, not just an essential expression but a necessity at the very heart of life. It becomes prayer beyond prayer. In Sutzkever's extraordinary poem and song 'Unter Dayne Vayse Shtern' it is indeed prayer itself: 'under your white stars/offer me your white hand/all my words are flowing teardrops/I would place them in your hand.' It is hope beyond the harrowing, beyond 'the murderous quiet'. At the end of the documentary, one survivor, Theodore, reflects that humanity still seems to want more of such tragedy, not yet having learned its lessons. Like the story and the songs, it is a sobering observation. Like the story and the songs however, it is not an expression of defeat and resignation but of centred humanity and continued hope. There is appropriate 'forgetfulness' in the story, for many survivors the only way to survive. Yet this is also subversive memory and a life-giving poetry of hope.  If William Blake had lived today, I suspect he would have had a field day. He would have thrived as an all-round artist in our multi-media age and he would have been a vital voice for visionary sanity in our blinded days. Such is my sense amid my deepened passion for Blake on visiting the current exhibition of some of his visual art in the National Gallery of Victoria this week. For, despite the strangeness of elements of his work, what we continue to discover in Blake is an astonishing wholeness of vision, mediated by word and image, poetry and politics, religion and the secular, all held together.. The NGV has a surprisingly large collection of Blake's watercolours, engravings and prints and the present exhibition is the first in fifteen years to showcase them. Not least this includes 36 of Blake's 106 portrayals of Dante's work, striking in their myth and meaning. It was a vivid demonstration of the importance of word and image in unity. Indeed I realised how much we often think of Blake as merely a poet and wordsmith (albeit such a great one), when his visual work is so central. He began his working life as an engraver and this was what brought him the bulk of his income, small though that remained throughout his life. His biography is certainly also a reminder of that other England which is frequently overlooked and underestimated. This is the England of struggle and solidarity, of nonconformist humanity and the very best kind of eccentricity. It is the England of Milton and Shelley, with whom, with contemporaries like Mary Wollstonecraft, Blake forms a blessed genealogy, imbued with radical and generous republican hope. Blake's vision is of a world in which Albion and Jerusalem are one: material and spiritual together, alive with grace and love. In the face of today's constraining functionalism, his is still such a liberating cry for freedom, and for imagination and not mere 'reason' as the source of life and joy. As he wrote, 'prisons are built with the stones of law, brothels with bricks of religion'. Instead, we need to cultivate the contemplative, being true visionaries of word and image, understanding and doing: ''To see a World in a Grain of Sand/And a Heaven in a Wild Flower/Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand/And Eternity in a n hour.' For, in a vision as necessary today as in his own day, and demonstrated in the various interwoven facets of his life and work, Blake was right: 'A Spirit and a Vision are not, as the modern philosophy supposes, a cloudy vapour, or a nothing: they are organised and minutely articulated beyond all that the mortal and perishing nature can produce.' Not for nothing have I had words of Blake above my office desk for several years: 'Imagination is evidence of the divine.' Mary Oliver's beautiful poem 'The Summer Day' encapsulates so much of the real challenge of a spiritual life. As she writes elsewhere, in 'Wild Geese': 'You do not have to be good./ You do not have to walk on your knees/ for a hundred miles through the desert, repenting./ You only have to let the soft animal of your body love what it loves.' How hard it often is for us to believe, and, still more, trust and live this. We have so often allowed ideas of exile, death, sin and punishment to predominate in our psyches, rather than welcome, life, grace and forgiveness, which are so much more central and eternal. All too often even so-called rebels, rakes and critics have protested, and lived, a false dichotomy between the material and spiritual, the now and beyond, the human and divine. Mary Oliver instead calls us to attention, to the mystery of the everyday and everywhen, and to living of life in all its fullness.

The final words of the poem 'The Summer Day' have also been ringing round my consciousness for the last two and a half months: 'Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?' Perhaps this blog and website is but one small step for me in responding to that challenge, an expression of my own call to attention, and to expression of the mystery and meaning I glimpse and seek to live. Maybe my good soul-friend Graham is right, self-effacement can be a frustrating buried treasure. Graham introduced me to Mary Oliver's work and a wild and precious life certainly demands more. That phrase also came alive for me this weekend as I pondered two men whose funerals I had been asked to lead. One died only a year older than I am now. Like Bob Dylan's admission about Lenny Bruce, 'maybe he had some problems, maybe some things that he couldn’t work out', but he was more spiritually awake than many. Bruce Laurie was somewhat wild in several senses, but he was also precious and he lived life to the full. The other man was a Toowoomba country man of the old school but of a high intellectual calibre. His late wife Olwen was a weekly communicant in our Anglican parish but Reid was more complex, not just more shrewd but more sparing, in his spiritual commitments: perhaps his very unpretentiousness kept him from expressing publicly, or aloud, the deepest longings and experiences of his heart. He was full of life and virtues however, which shine on in his grieving children. He paid attention and seized life's opportunities and challenges, passionately but graciously. Now he rides his wild horses beyond the western sunset and into a new summer's day. He, like Bruce, would have loved to have argued and agreed with Mary Oliver's poet-forerunner Horace, drowning a beer together on the verandah (or in Bruce's case perhaps something stronger in a nightclub): Carpe Diem. May they rest in peace and rise in glory, and may we attend and let the soft animal of our bodies love what they love. |

AuthorJo Inkpin is an Anglican priest serving as Minister of Pitt St Uniting Church in Sydney, a trans woman, theologian & justice activist. These are some of my reflections on life, spirit, and the search for peace, justice & sustainable creation. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed