|

It is (sadly) interesting to me that, whilst I am a lifelong Anglican, and one with decades of helping lead Anglican teaching and formation, my mother Church tradition rarely asks me to contribute to ways out of its neurotic obsessions with sexuality and gender, whereas others in other spaces do (‘a prophet is not without honour’ and all that?).

Here is a latest offering, with thanks to The Sisters of the Good Samaritan for the opportunity to offer a brief perspective on how flourishing LGBTIQA+ lives flow out core elements of Catholic wisdom down the centuries - not least in considering family, the Body, natural law, the imago dei, and God’s grace in Creation. For: ‘this is about reclaiming Catholic emphases on the centrality of God’s grace in the diverse expressions of creation and incarnation, rather than imposing false ideas of sin and shame on those who are actually gifts to help lead us into greater life together. LGBTIQA+ people of faith do not need welcome, or inclusion, for we are already at home with God, as family members and part of Christ’s Body, wholly natural, and imaging the divine in our diverse ways. What we do need is space to flourish, and thereby we can enable others to flourish also.’ See link to the article iFlourishing Together' in The Good Oil here - or text below...

0 Comments

Loving the creative hearts beginning to appear from folks at Pitt Street - here are a few examples (my current favourite being a fellow trans person’s ‘Love’ heart - as I know that comes from a deep journey ) - part of our #returningourhearts Lenten theme, as part of ‘repairing the breach’.

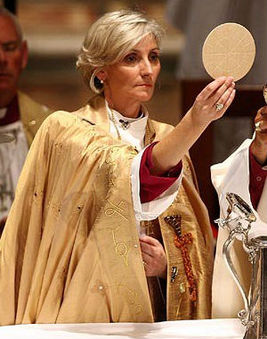

More splendid creativity at Pitt Street from our worship team 😻 And - sad though I am not to share a first Pitt Street Christmas - I’m so delighted that my brilliant wife (Penny Jones) could preside yesterday. That is the first time for her with our community in Pitt Street - and maybe the first time a female cisgender Anglican priest has presided, with full church authority, in a mainstream Christian denomination in the centre of Sydney. ❤️ I think Maude Royden, the founder of the movement for the ordination of women, will have rejoiced in heaven - especially as Pitt Street gave her a pulpit on her famous visit to Australia years ago (see earlier post here). Hoping one day our good friends in some of the local Anglican and Catholic Churches will share the same blessing - for God’s sake, it was a woman who actually gave birth at Christmas!! It is just lovely to have a female vicar here in Market Rasen at this time and to think of female priests elsewhere in Australia presiding this year (some for the first time - including some of my former students I dearly love and admire). #shininglightinSydney #thankGodfortheUnitingChurch #livingAnglicanism #peacetoall  ‘It is time that leading politicians and religious leaders stopped abusing religion to hurt people and cling to power’, said the Revd Dr Josephine Inkpin, a transgender Anglican priest and Minister of Pitt Street Uniting Church in Sydney, speaking ahead of this Saturday’s protest at Sydney Town Hall against the One Nation ‘religious freedom’ and ‘parental choice in education’ Bills in NSW Parliament. ‘As I, and so many people of faith embody,’ she said, ‘there is no necessary conflict between being part of the LGBTQ+ community and being a person of faith. The attempts to drive a wedge between people undermines our nation’s shared commitments to human rights and a ‘fair go’ for all. Jesus was quite clear – ‘love your neighbour as yourself’ is at the heart of divine law and compassion. Shockingly however, the cross, a symbol of love for all, is turned upside down by some to become a sword to damage others'...  As I come, this Saturday, to give my final lecture as a St Francis College Brisbane staff member, it is poignant to do so on the subject of ‘The Vocation of Anglicanism’. In that light, it is such a delight to find today an Ad Clerum from Bishop David Jenkins - written in 1993, in the white heat of conflict, as the final legal steps for the ordination of women went through Parliament. It is a typical +David description of the Anglican (Church of England) spirit in which I was raised - so far from so much that passes as Anglican in some places today - not least these key points which also sit so happily with the UCA ‘Basis of Union’ ... One of the most life-giving parts of my ministry in Toowoomba was the installation of the Reconciliation Cross in St Luke's Anglican Church. Created by renowned Aboriginal artist Uncle Colin Isaacs, as a gift from Heather Johnston (a descendant of one of the original European settlers), this commemorates the great Aboriginal leader Multuggerah, the Battle of One Tree Hill, and Aboriginal resistance to invasion and dispossession. It was overseen with the guidance and leadership of the late Uncle Darby McCarthy and other local elders, with particularly notable support from Mark Copland (from the Social Justice Unit of the Catholic diocese of Toowoomba). It represents a vital visible step in Australian Reconciliation, affirming a continuing journey for recognition and justice. For, in these days of #BlackLIvesMatter and questions about 'white' history and memorials, it offers a tangible example of what can be done to renew our histories and nurture new symbolism and focal points for a better future together. In my view, as both an historian and a priest, it is undoubtedly appropriate that some, more offensive, statues and other historical artefacts are replaced and/or re-used in new ways. Others might have constructive adaptations or additions made. Both of these courses have indeed been employed, on church owned sites, as part of Church practice in addressing the legacy of, and memorials, to child abusers, and those who have colluded with them. Much much more important however is addressing living injustices and forging new pathways. Reclaiming Australia's 'black history' is a crucial aspect of this and Toowoomba's Reconciliation Cross is a living symbol.. It is therefore a cause of thanksgiving that it is placed in the centre of Toowoomba, in one of its oldest and most significant spiritual buildings, available for anyone to visit, to ponder and to encourage the next urgent steps in the journey of justice and healing...

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall.

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall. All the Pope’s horses and all the Pope’s men (and women), couldn’t put Humpty together again. For good and ill, the era we know as the Reformation has hugely shaped us. It involved immense fragmentation: both a breaking down and a breaking open. Like Humpty Dumpty, that which went before had ‘a great fall’ and could not be put together again as it had been. Especially within Christian life, it has thus bequeathed so many features we simply take for granted. Some have lasting value. Others are much more questionable. This includes the very existence of different Christian traditions, in what, from the 19th century, we have termed denominations. This was not, of course, an intended outcome. Indeed, it would have seemed anathema to any Reformer, as well as to the Church of Rome. Yet it is part of our Reformation inheritance. So what do we make of this, for God’s continuing mission? What is worth keeping? How might we move on together? This reflection is not a traditional potted history. Nor does it seek to draw us into comparisons of our different Christian traditions, never mind reassemble past dynamics and rhetoric. Instead, it outlines briefly both vital differences and also important similarities between that age and our own. In doing so, it identifies a number of negative features which often mar our churches and world. It also suggests a number of positive features which can heal and take us forward. Hopefully, in the contemporary spirit of ‘receptive ecumenism’, these may then provide a basis for assessing which Reformation gifts we will own together and which we will leave behind. What else, we might then ask, do we need for our journey onwards today?... It is baffling and frustrating to hear some politicians, media and other leaders talk about a lack of Muslim response to terrorist and other Islamist-linked outrages. It seems as if sometimes people simply only want to see and hear what they want to see and hear. Earlier last week the following open letter from our Islamic community to our local Toowoomba Catholic bishop was received by myself and other faith and community leaders. It speaks of the continued revulsion of almost all Muslims to acts such as the recent killing of Father Jacques Hamel and the deep shared commitment to peace and humanity...

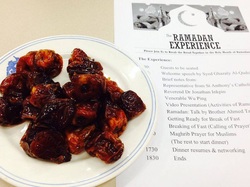

In its remarkably unhelpful article on the Church of England's belated decision to move for female bishops, Catholic Online (15/7/14) makes one of those knee-jerk denominational reactions which do little credit to the wisdom of its own tradition, never mind the complex truth and relationships of ecumenical life. As a leading Roman Catholic communication channel, it is a disappointing response and one which must, at the very least, make many Catholics cringe. Whilst the article rightly raises the ecumenical challenge contained in the emergence of female bishops in the Anglican Communion, it vastly overstates the continuing divisions, ignores the nuances and other positive dynamics of Roman Catholic ecumenism, and, above all, fails to understand that the journey of Christian unity is not a one-way street. Perhaps, like other instinctive Christian reactionaries, the author feels a sense of betrayal as the Church of England stumblingly implements a very Catholic principle of doctrinal development to help ensure historic Christianity remains credible and alive in the changed context of the contemporary world...  Wednesday evening was a delightful example of the nature of interfaith peace and harmony life in Toowoomba. Not only were members of our Muslim community wonderfully warm and welcoming but all kinds of people were present from across our diverse wider community. And it all took place on Christian premises, at St Anthony's Catholic Church in Harristown. Jesus, I think, was smiling: all God's children together, sharing 'table fellowship', sharing faith and food, life and laughter together. Sharing the evening Iftar (breaking of the fast) with others has become a very valuable and enjoyable part of Australian life. Each year, many Australians of other faith and none happily experience the generous invitation of their Muslim neighbours to join in this important part of the Muslim year and to grow in deeper understanding and love together. Thanks, in Toowoomba, go out especially to the coordinators of the Islamic Interfaith and Multicultural Committee. For, as a spiritual gift, hospitality is one of the most vital contributions anyone can make to peace and harmony. It is certainly one aspect of Ramadan which enriches others, though not the only one. Ramadan, like daily prayer in Islam, is also a gift to recall the rest of us to attentiveness, mindfulness and the presence of God. It is a binding force for community, here and across the world. It helps release our society from the compulsions to consume and blunt our senses with material things alone. Indeed, only when we know how to fast (in various ways) do we really feast properly. 'Let us cherish fasting', Athanasius, the great early Christian bishop and theologian said, 'for fasting is the great safeguard along with prayer and almsgiving. They deliver human beings from death.... (for) to fast is to banquet with angels.' Delivered from the destructive powers of self, we can then be more generous and hospitable towards others. Hospitality is certainly a central theme of Anglican inter-faith and cross-cultural endeavour. As the helpful international Anglican document Generous Love puts it: As God both pours out his life into the world and remains undiminished in the heart of the Trinity, so our mission is both a being sent and an abiding. These two poles of embassy and hospitality, a movement ‘going out’ and a presence ‘welcoming in’, are indivisible and mutually complementary, and our mission practice includes both. This kind of hospitality is therefore an expression of the very nature of the God whom we approach in different ways. Such true hospitality is not about losing, but expressing, our integrity and convictions. Rather, we in turn can then receive the gifts of others, which can speak powerfully of the welcoming generosity at the heart of God. For , as Generous Love reflects: through sharing hospitality we are pointed again to a central theme of the Gospel which we can easily forget; we are re-evangelised through a gracious encounter with other people. Transformed by God, we become paradoxically both deeply centred and radically open, for our centre is self-giving love. Faith is not then based on human work, such as particular belief or practice, but on grace. In all the great spiritual traditions, fasting and feasting are gateways and expressions of this. |

AuthorJo Inkpin is an Anglican priest serving as Minister of Pitt St Uniting Church in Sydney, a trans woman, theologian & justice activist. These are some of my reflections on life, spirit, and the search for peace, justice & sustainable creation. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed