|

Avrom Sutzkever, in his own words, speaks of his staggering experience of the Shoah and the incredible power of poetry to bring hope and triumph over the very worst of human experience...

0 Comments

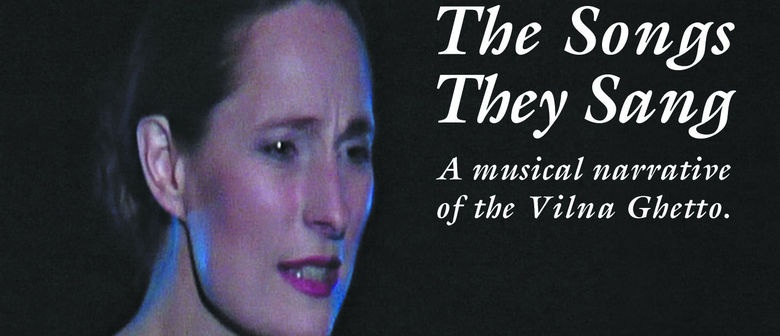

A chance visit to the Balaclava area of Melbourne led me this week to pick up a flyer in a cafe for a deeply moving documentary (entitled 'The Songs They Sang') on the experiences of the Vilna (one Vilnius) ghetto. Negotiating my way to the delightful, and somewhat accurately named, Backlot Studios, I was variously challenged and inspired by the horrendous inhumanity, and the courage, hope, poetic and practical resistance of those had lived and died in that terrible time. I was also reminded how important it is to keep hope alive, even in the most desperate of circumstances, and to carry forward memory, so that light can continue to shine and triumph again in our world's persisting darkness. I was but one of a handful of people at the showing yesterday, and all but one other were older East European Australians. Yet the beautiful and poignant understated documentary, and accompanying CD of the songs from the ghetto, continue to share the story and lead to sanity for others too.

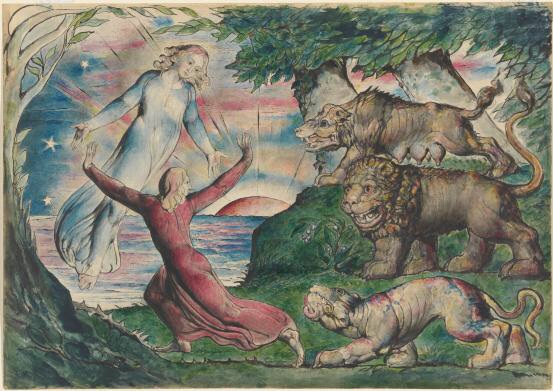

This work is timely, both for the Jewish community and for the wider global community as it endures further horrors of genocidal and ideological madness. As the last survivors of the Shoah dwindle, it is vital that their songs and stories are shared. A major theme of the documentary is indeed that of the third generation of ghetto survivors and it begins with a granddaughter returning to Israel for her grandfather's funeral. Like the Jewish children singing in Vilna today the ghetto songs, the affirmation of the later generations that 'we are here' is a powerful expression of hope and the reality of life surviving even abject and extraordinary death. For the experience that is related speaks both of what was and what is and will be. In the face of the ghetto's horror, and the daily encounter with death (close at hand or in the killing fields of the nearby Ponar forest), the Jewish community used theatre to keep the spirit alive. In this they were aided by remarkable people, such as Amroz Sutzkever. Probably the greatest Yiddish poet of the holocaust and one of the most outstanding poets of the whole 20th century, Sutzkever's words were both brilliant in their expression and amazingly strengthening amid the scarcely imagineable harrowing. Nor was he alone. One of the most powerful parts of the whole documentary is the song Mother, written by Chayele Posnanski after the murder of her mother. She herself also did not survive the war and this is the only legacy she left. Like Satzkever's work, the song acts as a means of transcendence, an affirmation of life in the midst of the almost unbearable grief of existence. Poetry is thus, like other arts, not just an essential expression but a necessity at the very heart of life. It becomes prayer beyond prayer. In Sutzkever's extraordinary poem and song 'Unter Dayne Vayse Shtern' it is indeed prayer itself: 'under your white stars/offer me your white hand/all my words are flowing teardrops/I would place them in your hand.' It is hope beyond the harrowing, beyond 'the murderous quiet'. At the end of the documentary, one survivor, Theodore, reflects that humanity still seems to want more of such tragedy, not yet having learned its lessons. Like the story and the songs, it is a sobering observation. Like the story and the songs however, it is not an expression of defeat and resignation but of centred humanity and continued hope. There is appropriate 'forgetfulness' in the story, for many survivors the only way to survive. Yet this is also subversive memory and a life-giving poetry of hope.  If William Blake had lived today, I suspect he would have had a field day. He would have thrived as an all-round artist in our multi-media age and he would have been a vital voice for visionary sanity in our blinded days. Such is my sense amid my deepened passion for Blake on visiting the current exhibition of some of his visual art in the National Gallery of Victoria this week. For, despite the strangeness of elements of his work, what we continue to discover in Blake is an astonishing wholeness of vision, mediated by word and image, poetry and politics, religion and the secular, all held together.. The NGV has a surprisingly large collection of Blake's watercolours, engravings and prints and the present exhibition is the first in fifteen years to showcase them. Not least this includes 36 of Blake's 106 portrayals of Dante's work, striking in their myth and meaning. It was a vivid demonstration of the importance of word and image in unity. Indeed I realised how much we often think of Blake as merely a poet and wordsmith (albeit such a great one), when his visual work is so central. He began his working life as an engraver and this was what brought him the bulk of his income, small though that remained throughout his life. His biography is certainly also a reminder of that other England which is frequently overlooked and underestimated. This is the England of struggle and solidarity, of nonconformist humanity and the very best kind of eccentricity. It is the England of Milton and Shelley, with whom, with contemporaries like Mary Wollstonecraft, Blake forms a blessed genealogy, imbued with radical and generous republican hope. Blake's vision is of a world in which Albion and Jerusalem are one: material and spiritual together, alive with grace and love. In the face of today's constraining functionalism, his is still such a liberating cry for freedom, and for imagination and not mere 'reason' as the source of life and joy. As he wrote, 'prisons are built with the stones of law, brothels with bricks of religion'. Instead, we need to cultivate the contemplative, being true visionaries of word and image, understanding and doing: ''To see a World in a Grain of Sand/And a Heaven in a Wild Flower/Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand/And Eternity in a n hour.' For, in a vision as necessary today as in his own day, and demonstrated in the various interwoven facets of his life and work, Blake was right: 'A Spirit and a Vision are not, as the modern philosophy supposes, a cloudy vapour, or a nothing: they are organised and minutely articulated beyond all that the mortal and perishing nature can produce.' Not for nothing have I had words of Blake above my office desk for several years: 'Imagination is evidence of the divine.'  On behalf of Angligreen, it was a delight yesterday to share in the 'Debate the Preacher' series at St John's Cathedral in Brisbane, exploring environmental ethics. I found myself drawing on recent experience of Aboriginal approaches to land and the cosmos. These can be part, I believe, of ways of re-reading our world, ethics, bible and sacred traditions which enable a fresh and more fruitful Pentecostal understanding of life. Through this, we are challenged and inspired to eco-Living in the Spirit. For, to our loss, we have so confined our understanding of Pentecost to human, and often restricted personal and ecclesiastical, experience. Instead, Pentecost perhaps offers us vital ways in to more fruitful engagement with the heart of many of our contemporary challenges, not least ecological ones, as well as cross-cultural and inter-religious. Not for nothing is Pentecost understood theologically as a new creation. Check out my address here.  As part of the Toowoomba Churches Together marking of the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity, Toowoomba Ecumenical Environmental Network held a vigil prayer on the evening of 4 June in St Luke's for World Environment Day. We were joined by Emily Gentle, a local resident whose family still live in Kiribati. She spoke movingly about the challenges faced by Kiribati, not least those of climate change upon such a vulnerable Pacific community. This brought home to us the realities of small island states which are the focus of the UN's World Environment Day this year. In the words of the collect I wrote for Angligreen this year, may we therefore act and pray: Holy God, source of all life and unity, we give you thanks for the gifts of the small islands and oceans of our world. As the Holy Spirit moves upon the waters of new life, grant that we too may share in your renewing love, hearing the groans of creation and raising our voices in solidarity, that your will may be done, and all creation share in the waves of your embrace. This we ask in the name of Jesus Christ, through whom all things are reconciled. Amen.  Last Sunday it was both moving and a delight to celebrate the 20 years anniversary of the ordinations to the priesthood of my wife and colleague Penny Jones and our Glennie School chaplain Kate Powell. Both were part of the historic wave of female ordinations in England in 1994. As part of the gathering they shared something of their own journeys, including the pain and struggle to ordination (and, in Kate's case, the opposition of her own bishop, in Chichester, which led to her ordination by another bishop in a parish church at East Grinstead). The choice of songs, readings and poetry was telling and uplifting and it was a huge pleasure to be joined by people from the wider community as well as Glennie School and the Anglican parish of St Luke. We were reminded how this is but one more step on the journey of God's liberation of women and men: a 'teacup in a storm', offering comfort and encouragement. A particular joy was also the presence of other women from other denominations and religious faiths (including Venerable Wu Chin, from the Pure Land Buddhists, who brought a lovely gift of typical hospitality). |

AuthorJo Inkpin is an Anglican priest serving as Minister of Pitt St Uniting Church in Sydney, a trans woman, theologian & justice activist. These are some of my reflections on life, spirit, and the search for peace, justice & sustainable creation. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed