My years in Toowoomba were both full of wonderful things and also wrestling with the need to come out publicly in my authentic gender. So it has been good to reflect again on this as I responded recently to the invitation to share in the Make Visible project developed by artist Shannon Novak with the support of QAGOMA. This aims to grow support for the LGBTQI+ community in Queensland, Australia by making visible challenges and triumphs for this community. One of the satellite sites and partners is USQ at Toowoomba, who asked me to write a short letter, headed 'Dear Toowoomba'. They also invited me to be a part of the Launch of the project 'Its' ok to be me' at USQ and to share in a panel on ways forward. I hope my contribution may be part of contributing to the further maturing of a city with so many fine features and people, but still with a little more work to do in fully celebrating and empowering all its people. It has also reminded me of the many people (and a wonderful dog!) I miss in Toowoomba and its achievements and potential...

0 Comments

One of the most life-giving parts of my ministry in Toowoomba was the installation of the Reconciliation Cross in St Luke's Anglican Church. Created by renowned Aboriginal artist Uncle Colin Isaacs, as a gift from Heather Johnston (a descendant of one of the original European settlers), this commemorates the great Aboriginal leader Multuggerah, the Battle of One Tree Hill, and Aboriginal resistance to invasion and dispossession. It was overseen with the guidance and leadership of the late Uncle Darby McCarthy and other local elders, with particularly notable support from Mark Copland (from the Social Justice Unit of the Catholic diocese of Toowoomba). It represents a vital visible step in Australian Reconciliation, affirming a continuing journey for recognition and justice. For, in these days of #BlackLIvesMatter and questions about 'white' history and memorials, it offers a tangible example of what can be done to renew our histories and nurture new symbolism and focal points for a better future together. In my view, as both an historian and a priest, it is undoubtedly appropriate that some, more offensive, statues and other historical artefacts are replaced and/or re-used in new ways. Others might have constructive adaptations or additions made. Both of these courses have indeed been employed, on church owned sites, as part of Church practice in addressing the legacy of, and memorials, to child abusers, and those who have colluded with them. Much much more important however is addressing living injustices and forging new pathways. Reclaiming Australia's 'black history' is a crucial aspect of this and Toowoomba's Reconciliation Cross is a living symbol.. It is therefore a cause of thanksgiving that it is placed in the centre of Toowoomba, in one of its oldest and most significant spiritual buildings, available for anyone to visit, to ponder and to encourage the next urgent steps in the journey of justice and healing...

‘Once we see God as an artist, everything changes’ (John O’Donohue). For God’s work is like an artist, shaping life’s raw materials into new forms of beauty, truth and justice, through love. Sometimes we think of God too much as a law-giver or police officer, a mechanic or an engineer. All those occupations can also speak of God. Yet they can distance us from God’s intimate, costly and creative involvement with us, and from the invitation to share that love in similar ways with others. Art can thus reopen our eyes and ears and touch our souls and world afresh.

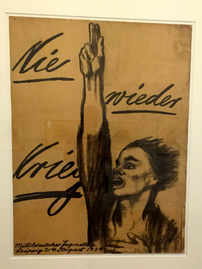

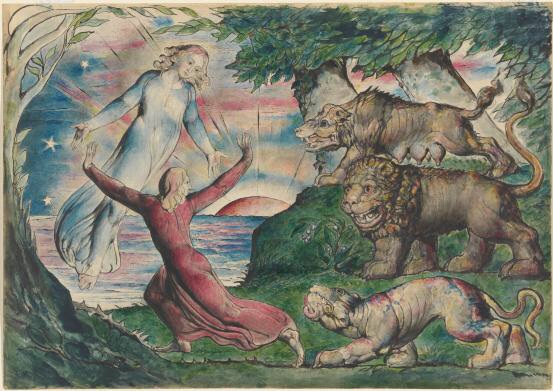

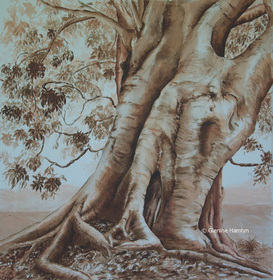

At St Luke’s Toowoomba, we see the community we call ‘church’ as a kind of ‘art-school of divine majesty’. Our building itself is indeed an artistic expression of God’s love. Recently we therefore installed art hanging rails better to share God’s love and creativity through art in the city’s heart. Beginning in Holy Week, and linked to the Streets and Lanes Festival on the Saturday before Easter, we have our first exhibition, with local artists reflecting visually on the Easter story. We hope it will inspire others to see God’s art among us and to grow as artists of God’s grace.  One of my main highlights of visiting Berlin this year was the Kathe Kollwitz museum. An artistic genius, Kollwitz' life and work are inspiring examples of the German soul. She was an outstanding pioneer for women, with a profound social conscience and identity. A committed socialist and pacifist, who shared the life of the poor with her doctor husband in Berlin's struggles, not for nothing was she commissioned to create a powerful memorial to the murdered Karl Liebknecht. Tragically, her compassion for the victims of war and oppression and the strength of poor women, especially mothers, was embodied in her own sufferings over the loss of her son in the first world war. Removed from her leading role in German arts and culture by the Nazis, she was eventually evacuated from Berlin in 1943 as foreign bombs wreaked violence, including, soon, the destruction of her own family apartment with its photographs and mementos of loved ones. A week later her son's home was also destroyed during a bombing raid. Kollwitz tellingly wrote in her journal: "every war already carries within it the war which will answer it. Every war is answered by a new war, until everything, everything is smashed... That is why I am so wholeheartedly for a radical end to this madness, and why my only hope is in a world socialism... Pacifism simply is not a matter of calm looking on; it is work, hard work." She died in 1945, 16 days before the end of the Second World War. Yet her transcendent art and inspiring hope, in and beyond suffering. lives on. Love this creative, and appropriately fresh democratic, way of marking Magna Carta...  If William Blake had lived today, I suspect he would have had a field day. He would have thrived as an all-round artist in our multi-media age and he would have been a vital voice for visionary sanity in our blinded days. Such is my sense amid my deepened passion for Blake on visiting the current exhibition of some of his visual art in the National Gallery of Victoria this week. For, despite the strangeness of elements of his work, what we continue to discover in Blake is an astonishing wholeness of vision, mediated by word and image, poetry and politics, religion and the secular, all held together.. The NGV has a surprisingly large collection of Blake's watercolours, engravings and prints and the present exhibition is the first in fifteen years to showcase them. Not least this includes 36 of Blake's 106 portrayals of Dante's work, striking in their myth and meaning. It was a vivid demonstration of the importance of word and image in unity. Indeed I realised how much we often think of Blake as merely a poet and wordsmith (albeit such a great one), when his visual work is so central. He began his working life as an engraver and this was what brought him the bulk of his income, small though that remained throughout his life. His biography is certainly also a reminder of that other England which is frequently overlooked and underestimated. This is the England of struggle and solidarity, of nonconformist humanity and the very best kind of eccentricity. It is the England of Milton and Shelley, with whom, with contemporaries like Mary Wollstonecraft, Blake forms a blessed genealogy, imbued with radical and generous republican hope. Blake's vision is of a world in which Albion and Jerusalem are one: material and spiritual together, alive with grace and love. In the face of today's constraining functionalism, his is still such a liberating cry for freedom, and for imagination and not mere 'reason' as the source of life and joy. As he wrote, 'prisons are built with the stones of law, brothels with bricks of religion'. Instead, we need to cultivate the contemplative, being true visionaries of word and image, understanding and doing: ''To see a World in a Grain of Sand/And a Heaven in a Wild Flower/Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand/And Eternity in a n hour.' For, in a vision as necessary today as in his own day, and demonstrated in the various interwoven facets of his life and work, Blake was right: 'A Spirit and a Vision are not, as the modern philosophy supposes, a cloudy vapour, or a nothing: they are organised and minutely articulated beyond all that the mortal and perishing nature can produce.' Not for nothing have I had words of Blake above my office desk for several years: 'Imagination is evidence of the divine.'  In Whitechapel Gallery at present there is a striking multimedia installation. Created by the French-Algerian artist Kader Attia, it uses the biblical story of Jacob's Ladder to address mind, memory, and meaning in our postmodern world. Indeed, it is is appropriately sited in the former Whitechapel Library, a significant 'crucible of British Modernism'. It explores what Michel Foucault called our human 'archaeology of knowledge': within which we live, move, shape and are shaped, whether we like it or not. Wandering through London, as I was on a brief transit visit, I had found myself wandering through features of my own life's memory and meaning and that of our wider world. Attia's work spoke powerfully of ways to engage fruitfully, not least through his concept of 'repair'.  It makes all the difference, John O'Donohue once said, whether you see God as an artist. Once you do, everything changes. For, as he observed so rightly, we have so over emphasised the will of God, and so devastatingly neglected the imagination of God, that we have deeply impoverished ourselves. For: Each of us is an artist of our days; the greater our integrity and awareness, the more original and creative our time will become. (in To Bless the Space Between Us: A Book of Blessings) I didn't used to regard myself as an artist. That is only for special people, I used to think, and you have to be very good at it. Now I know that that is bunkum. We are all artists. Some work with paint, clay, or other materials. Some with the human body and its expression. Others with music or words. Others shape places, communities, moments or people. For we are all made in the image of God, and the first divine blblical characteristic (read Genesis) is creativity: then, now and always. That is something I love about St Luke's church in Toowoomba. It comes marvelously alive when, at Carnival and at other much more ordinary times, it is clothed with the grace and creativity of God in human artistry. And it can happen every day, if we let it and embrace it...  For me, the church is therefore what a brave man once called 'an art school of divine majesty'. Think of that, or, better still, imagine that: feel it, and see what a difference it makes to your life and faith and that of others. What Fr George Tyrrell (see photo left) was trying to say is that being part of a religious tradition and community is like being part of an artistic tradition and community. There may be great 'masters' like Rembrandt who show the way. An artist may sit at their feet and learn and develop in that art school. For we do not make art by ourselves. That is an individualist fallacy. Yet there will come a time when every artist need to make this task their own. Perhaps they will even overthrow some of the foundational assumptions and shapes of their master: all however in the cause of deeper beauty, love and truth. Isn't that, said George Tyrrell, how faith evolves and expands? Tyrrell was a man of great courage. For, drawing on God's grace and the riches of the Church's tradition, he used his creative imagination, scholarly intelligence, pastoral sensitivity and deep religious learning to give new life to the Church of his day. Today many of his insights have been accepted, further critiqued and developed by Catholic and Protestants alike. However he was condemned by Pope Pius X, with other so-called Catholic Modernists, expelled from the Jesuit order, denied the sacraments, and finally excommunicated. He was not allowed a Catholic burial and was interred in an unmarked grave. A priest friend, Henri Bremond, who had the grace to make the sign of the cross over the grave, was himself, as a result, then suspended for a while. For being a religious artist is not always easy - just see what happened to Jesus. Yet being an artist, and part of an 'art school of divine majesty', is part of the gateway to resurrection: to greater and deeper life, beauty, truth and love, for us and for others. May the divine artist flourish in everyone.  Do you see the wood or the trees? Only a few seem capable of seeing both. My friend, and former ecumenical colleague, Glenine Hamlyn is one of these special people. She possess both a compassionate grasp of the world's crises (not for nothing has she worked in development issues) and also an acute sensitivity to the immediate and the specific. This is revealed in her art, something to which she is currently able to give more time and focus. The picture to the left (now hanging on a wall in my home) is a wonderful example. In the midst of busy Brisbane, this one Moreton Bay fig captured her attention and in it amazing detail is revealed. So many people pass by daily without really seeing it, just as we pass by so much without really seeing. An artist can thus draw us back to proper attention, not so that we lose the wood, but so that it comes alive with the intricate complexity which is true wholeness. |

AuthorJo Inkpin is an Anglican priest serving as Minister of Pitt St Uniting Church in Sydney, a trans woman, theologian & justice activist. These are some of my reflections on life, spirit, and the search for peace, justice & sustainable creation. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed