|

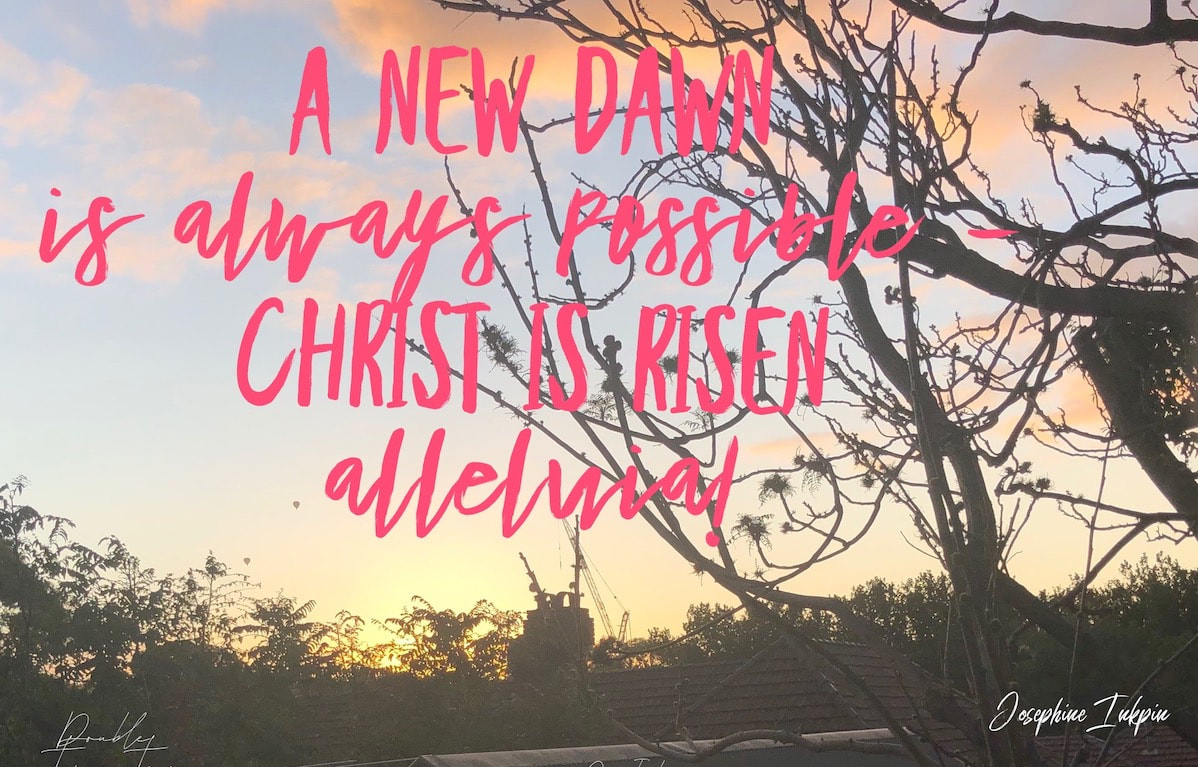

This photo was taken, earlier this year, from my bed of healing in a delightful unit in St Kilda (Melbourne). I had just had genital reconstruction surgery, thanks to the excellent skills of Andy Ives and his wonderful team at the nearby Masada Hospital, and I was in my first stages of recovery 'at home'. When the night's darkness began to lift, the new light of day brought this beautiful dawn. My eyes opened to the glorious gift of nature's renewal, and, with it, to the wonder of human participation in the joy of existence and work of re-creation. For across the sky, just above the treeline, floated a series of hot air balloons, beautiful expressions of fresh lightness and delight (you may just be able to spot two of them in the photo - as small circles to the left of the centre of the light, adjacent to the word alleluia). At the same time, the sunrise further gorgeously illuminated the cranes working on the building of the exciting development of the Victorian Pride Centre, visible a couple of streets away across the rooftops.

This experience was, as might be imagined, for me, a vision and harbinger of resurrection. It did not take away the struggles I was going through. The surgery itself was very successful, and there was not a subsequent shred of regret - so much the reverse, with deeper inner peace. Yet the days ahead also saw pain and discomfort, particularly with an awkward infection and a slow completion of healing due to sensitive skin (part of the joy of being a particular kind of natural redhead?!). The wider struggles of gender & sexually diverse people are also hardly over, despite such welcome living symbols of resurrection as the Pride Centre. Yet that dawn was not only a moment of special grace, but also a deep sign of hope and loving transformation, not simply for myself but for so much else about which I care. For resurrection, at least in this life and time space, is always betwixt and between...

0 Comments

Although aspects of Christian tradition have been devastating for physical love and comfort, the Jesus' story resounds with affirmation of the goodness of life, materiality and the senses. Touch is central to so many Jesus, and other holy, encounters. The body is not at all to be shunned. Rather it is, literally and spiritually, to be fully embraced, as a place where God is 'incarnate' (made flesh) among us. Of course, as with other aspects of life, there can be issues with use of the body, and its abuse by others, but it is fundamentally a beautiful, good, and loving gift of God. This is expressed in the very embodied nature of so much Christian sacramentality and liturgical action, including the sharing of the Peace and laying on of hands. One of the saddest things for many people right now, particularly those who are most isolated and/or lonely, is the further radical distancing of touch. The following prayer is thus partly a contribution to expressing this and finding other spiritual connection. It uses the practical tool, and embodying symbol, of the holding cross, which many people find helpful at times of stress, illness and loss. When we are unable even to speak due to pain, clasping such a spiritual aid can be life-giving and a means of receiving vital grace and strength. Even when others cannot hold us, we can ask for God's love to do so, and allow it to flow through us. In writing this prayer, the word 'lingering' came particularly to mind. It is less conventional than other descriptors of the divine but maybe especially evocative for these times. Perhaps, not least when church buildings and traditional elements are closed or silent, God is often among us as a more lingering presence, more like a whisper than a roar? That is also to affirm a more enduring reality than the 'signs of wonders' of much conventional religiosity. I offer it anyway as part of my prayer, in solidarity with others from whom I am currently physically apart. Do you have a holding cross? Could you perhaps make one, or more, for yourself and/or others? As I wrote this prayer I was particularly reminded of the late Sister Angela - the extraordinary Franciscan nun, mystic and sculptress/artist - whom I met years ago in Stroud in New South Wales. She taught me how to make my own wooden holding cross. I also give thanks for Les Rub, a beautiful friend and faith companion in Toowoomba, who has made so many holding crosses for others, distributed as a ministry to those in need in hospital, at home, or elsewhere. May such expressions of love, like this prayer, continue to hold and strengthen us and others, this day and always: Loving God we struggle to hold on amid fear and suffering. Hold on to us and help us hold on to the cross. Lingering God we struggle to wait amid stress and insecurity. Wait on us and help us wait with lingering faith. Living God we struggle to live amid death and despair. Live in us and help us live, even in the vale of destruction, in your eternal life.  In these times of coronavirus induced 'social isolation', it is salutary to reflect on those who have been leaders in practicing what we might call 'sacred isolation'. Indeed, I was happy recently to meet a request to write about St. Cuthbert, whose feast day falls this week. As a child of Northumbria, and the haliwerfolc (people of the saint) of Durham, it was a labour of love (there are certainly reasons his famous cross hangs, as in the photo above, in the window of my living room). My piece for Anglican Focus is entitled 'St Cuthbert - opening the door to the heart of heaven' (with homage to Malcolm Guite's fine sonnet), and can be found here. Sadly, in the Australian Anglican Lectionary, Cuthbert is remembered primarily as 'bishop and missionary'. His true significance however is much more than that: above all, as monk and hermit, in exploring life and God in silence, solitude, and intimate relationship with the 'word' of God in people, places, scripture and the 'book' of all Creation. Perhaps his commitment to 'sacred isolation' at the heart of his being is a particular gift to us today - not cutting us off from others, but enabling us to find deeper meaning, healing and solidarity in the midst of whatever life's circumstances throw our way? One of the refreshing characteristics of contemporary global Christianity is the recovery of balance in certain aspects of Christian life and thought. Features subjugated by the dominant Western Tradition re-appear to renew and transform. These include welcome affirmations of the God of life, women, children, 'ordinary people' and their lives and work, and the importance of the heart, creation and material existence, the body of Christ as all of us and the living Spirit of God. This is notably seen in many crosses fashioned in less powerful places which do not dwell lugubriously on death, pain and sin (like so much of Western tradition, not least that shaped by the Reformation era's obsession with mortality and finitude) Instead, in the colours and contours of different contexts, we find crosses becoming signs and places of resurrection: trees of life for and by the marginalised. This does not, of course, do away with what is valuable in such Western Tradition. Yet this shift towards an ethic of natality and flourishing is a great blessing for our world, recovering much that was lost. These few pictures in this slideshow (below) are just some: reflecting the dynamism, hope and down-to-earth realities of Latin America and Indigenous Australia: including a girl's cross; a women's cross; a family cross; the body of Christ today cross; and last supper of many nations. Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall.

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall. All the Pope’s horses and all the Pope’s men (and women), couldn’t put Humpty together again. For good and ill, the era we know as the Reformation has hugely shaped us. It involved immense fragmentation: both a breaking down and a breaking open. Like Humpty Dumpty, that which went before had ‘a great fall’ and could not be put together again as it had been. Especially within Christian life, it has thus bequeathed so many features we simply take for granted. Some have lasting value. Others are much more questionable. This includes the very existence of different Christian traditions, in what, from the 19th century, we have termed denominations. This was not, of course, an intended outcome. Indeed, it would have seemed anathema to any Reformer, as well as to the Church of Rome. Yet it is part of our Reformation inheritance. So what do we make of this, for God’s continuing mission? What is worth keeping? How might we move on together? This reflection is not a traditional potted history. Nor does it seek to draw us into comparisons of our different Christian traditions, never mind reassemble past dynamics and rhetoric. Instead, it outlines briefly both vital differences and also important similarities between that age and our own. In doing so, it identifies a number of negative features which often mar our churches and world. It also suggests a number of positive features which can heal and take us forward. Hopefully, in the contemporary spirit of ‘receptive ecumenism’, these may then provide a basis for assessing which Reformation gifts we will own together and which we will leave behind. What else, we might then ask, do we need for our journey onwards today?...  Yesterday I was given a marvelous gift from a remarkable artist of both life and embroidery. This is a person of great grace and determination who, little known to most people, was a courageous female pioneer in her field of work, also engaging with Indigenous people in other places long before it was 'fashionable' (if it ever has been in a positive sense). At the same time, she has been an amazingly skilled and prolific needlewoman, whose creations, soaked in prayer and deep reflection, richly adorn not only much of the parish of St Luke Toowoomba but many other places besides. I was overwhelmed by the generosity of this gift and also the beauty, skill and insight which has gone into it. For as my blessed benefactor put it, in an accompanying card: Traditionally the needlepoint group gave a piece of needlepoint to outgoing priests from this parish. This continues that practice. It was worked with care and consideration in in appreciation of all you have done in the parish and community. The four arms of the cross symbolise the outreach in all directions. Celtic knot work has no beginning or ending but one has to start somewhere - so in your new position may that outreach continue. On the eve of the feast of St Hilda of Whitby, it is hard to express the Celtic Christian call to mission better, in a medium so resonant of Celtic spirit. I feel richly blessed.  The Hills Hoist is one of the great Australian icons. It is in many ways redolent of much of modern Australia: happily and effectively secular, suburban and spiritually practical and pragmatic. It is simple, straightforward and sensible. It is easily owned by all cultures and backgrounds and found across the continent, from the cosmopolitan coast to regional backyards, to outback and desert landscapes. It requires no special insight, ritual or tradition. Yet the eye of faith may contemplate its cruciform design with wonder. Grounded in the sacred earth, clothed with humanity, raised to the heavens, its ordered, waiting, being is open to the dynamic grace and play of the elements, not least the sun and wind – metaphors of the life-giving Word and Spirit. Unassuming icon – heaven in ordinary.  “If one part suffers, every part suffers with it." (1 Corinthians 12.26) - this is part of the reality of our contemporary lives in the one world we now inhabit. It is very difficult not to be affected by the sufferings of other parts of the world, particularly if we share in Christian relationship. The situation in Iraq is a particularly grave one. As the Archbishop of Canterbury observed recently: what is happening right now in northern Iraq is off the scale of human horror… we cry to God for peace and justice and security throughout the world, and especially for Christians and other minority groups suffering so deeply in northern Iraq. It is therefore a sad but important duty to share in prayer and solidarity with those who suffer. As we do so, so much of scripture also comes alive in a powerful manner and we are drawn back to the cross and mercy-power of God.  Yesterday, in St Luke's Church, we shared a particularly poignant Prayer together with other Christians. The initiative was from a young Christian, Courtney Heyward, from another (independent Evangelical) church, who has been touched to the heart by the situation in Iraq. It was a reflective occasion, with readings from scripture interspersed with times for silent or shared prayer. Stones, or 'prayer rocks', were given to everyone present to hold as we prayed, reminding us of the hard things endured by others (including the burying of loved ones by the side of the roads of flight) and of the rock of God's love at the heart of all things. Towards the end of the gathering, each of us laid our stone at the foot of the cross and lit a candle of hope. We also shared some ways in which we may offer practical support to the persecuted, including giving to appeal funds and advocating for the needs of refugees. May God's mercy and strength comfort, turn the hearts of those who inflict terror, grant wisdom to those in leadership, and renew all who suffer. |

AuthorJo Inkpin is an Anglican priest serving as Minister of Pitt St Uniting Church in Sydney, a trans woman, theologian & justice activist. These are some of my reflections on life, spirit, and the search for peace, justice & sustainable creation. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed