painting by Andrey Shiskin painting by Andrey Shiskin I’ve always loved the ‘hinge’ time in the Christian year at the beginning of February - with the poignancy of time, light, joy and suffering in the Presentation of Christ/Candlemas, as well as its embodied meanings in places and people so varied as the dale farmers on my native hills preparing forw animal and plant births and the shiny school students in Sydney beginning new adventures at the same time. This year was particularly poignant, as, before our Pitt St worship, the last time I had heard the Nunc Dimittis was at my parents funeral (shall I say the nunc dimittis? the vicar had asked me specifically - in a very priest to priest moment - knowing the answer and what it meant to us both, and to my father). These lines from the poem ‘Nunc Dimittis’ (originated dedicated to the great fellow poet Anna Akhmatova) by Joseph Brodsky express so well the Christian hope, reflected in Candlemas, which my parents carried in their last days, in the meeting of age and infancy, and in the eternal uncreated light: ‘He went forth to die. It was not the loud din of streets that he faced when he flung the door wide, but rather the deaf-and-dumb fields of death’s kingdom. He strode through a space that was no longer solid. The roaring of time ebbed away in his ears. And Simeon’s soul held the form of the Child -- its feathery crown now enveloped in glory -- aloft, like a torch, pressing back the black shadows, to light up the path that leads into death’s realm, where never before until this point in time had any man managed to lighten his pathway. The old man’s torch glowed and the pathway grew wider.’ So be it..

0 Comments

It was a delight, in our strange times, to meet the trees on Pitt Street again this week - though, sadly, it’s not hard to find our wonderful church building as they are the only trees left on Pitt Street: like the building and its community they are natural resisters and witnesses to a better, more loving, sustainable way of life. The trees touch, and are enwombed, in Gadigal land and in the hope of a different kind of Sydney. May we see, work for, and be signs of, that in days to come, and not a mere new ‘normal’

On this New Year's Eve, 4 000 people took refuge from bushfires on the beach at Mallacoota in Victoria. The dramatic pictures - full of burning, smoke, and red skies - understandably drew forth words such as 'apocalyptic'. With two more lives lost today, together with many houses, the unprecedented series of bushfires across Australia cast a strong pall over the nation. The evacuation on the beach is but one powerful symbol, but, in the apocalyptic mood, it vividly makes fact the fiction of the famous film On the Beach (released in 1959, starring Gregory Peck, Ava Gardner and Fred Astaire), with its Melbourne 'end of the world' scenes. This is not the product of nuclear devastation however, but of the wilful neglect of decades of climate research and the 'she'll be right' blinkered stubborness of so much Australian and worldwide 'leadership'. It is a fierce verdict on such self-obsessed, and ultimately self-destructive, politics which have been so prominent in so much of the world this year. At the turn of this year therefore, lament, rather than looking forward, may seem most appropriate. What hope do we find?... Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall.

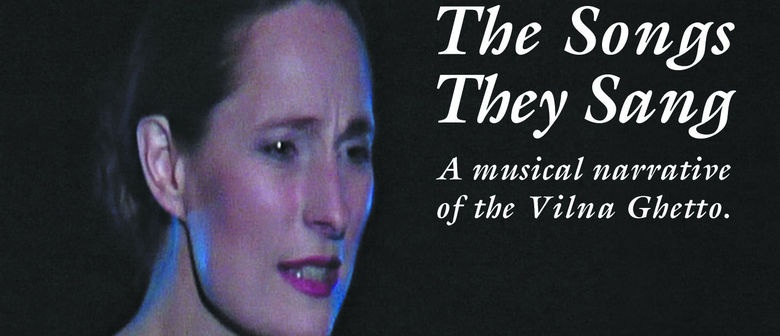

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall. All the Pope’s horses and all the Pope’s men (and women), couldn’t put Humpty together again. For good and ill, the era we know as the Reformation has hugely shaped us. It involved immense fragmentation: both a breaking down and a breaking open. Like Humpty Dumpty, that which went before had ‘a great fall’ and could not be put together again as it had been. Especially within Christian life, it has thus bequeathed so many features we simply take for granted. Some have lasting value. Others are much more questionable. This includes the very existence of different Christian traditions, in what, from the 19th century, we have termed denominations. This was not, of course, an intended outcome. Indeed, it would have seemed anathema to any Reformer, as well as to the Church of Rome. Yet it is part of our Reformation inheritance. So what do we make of this, for God’s continuing mission? What is worth keeping? How might we move on together? This reflection is not a traditional potted history. Nor does it seek to draw us into comparisons of our different Christian traditions, never mind reassemble past dynamics and rhetoric. Instead, it outlines briefly both vital differences and also important similarities between that age and our own. In doing so, it identifies a number of negative features which often mar our churches and world. It also suggests a number of positive features which can heal and take us forward. Hopefully, in the contemporary spirit of ‘receptive ecumenism’, these may then provide a basis for assessing which Reformation gifts we will own together and which we will leave behind. What else, we might then ask, do we need for our journey onwards today?...  As we let go of one year and begin another, it is good to give thanks for all that has been and to open ourselves with fresh hope and compassion to the future. The two things are connected. My final visit in Berlin this year for example was a way of paying tribute both to past inspiration and to its continuing living 'subversive memory'. For in the Friedrichsfelde Central Cemetery are the graves of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, among others commemorated at this Memorial to the Socialists. Other parts of the cemetery also house the graves of creative people, including the amazing artist Kathe Kollwitz. In some ways it is a sad place, not only as cemeteries typically can be, but also because of the failure of much of the vision and hard work of those buried there. Yet as the main commemorative stone has it Die Toten mahnen uns (The dead remind us), at their best, prompting us to renewing life and love. My politics have never been quite those of Liebknecht and Luxemburg, but I have always admired their commitment to a better world, sacrificial solidarity with the poor and outcast, intelligence and vision. To lay a flower on each of their graves was thus for me to express a debt of gratitude and to pledge with others to renew their work in a new way. My guess is that, in Rosa Luxemburg's case for sure, if they had not been murdered by the Freikorps in Berlin in 1919, their work would have been betrayed by others, including those indeed like one or two of the East German communist party apparatchiks buried alongside them. For being of Polish birth and Jewish extraction, and a feminist socialist with a physical disability and a brilliant independent mind, Rosa was always an uncomfortable figure to so many. Her most famous words sum this up and remain a powerful challenge and inspiration, whatever group(s) we belong to: Freedom only for the supporters of the government, only for the members of a party – however numerous they may be – is no freedom at all. Freedom is always the freedom of the dissenter. Not because of the fanaticism of "justice", but rather because all that is instructive, wholesome, and purifying in political freedom depends on this essential characteristic, and its effects cease to work when "freedom" becomes a privilege. For those words alone my pilgrimage would have been worthwhile, but there is much more. For to me, Rosa stands for many more, living and dead, who continue to believe in, inspire, and work, for another kind of world, however we imagine what Christians like me call 'the kingdom of God'. And so, for the coming year, in the words of the anarchist poet Pietro Gori, in Primo Maggio, written in 1890: Green May of humankind, Give your courage and your faith to our hearts. Give flowers to the rebels who failed Their sight fixed upon the break of dawn, To the bold rebel who fights and works To the far-seeing poet who sings and dies. A chance visit to the Balaclava area of Melbourne led me this week to pick up a flyer in a cafe for a deeply moving documentary (entitled 'The Songs They Sang') on the experiences of the Vilna (one Vilnius) ghetto. Negotiating my way to the delightful, and somewhat accurately named, Backlot Studios, I was variously challenged and inspired by the horrendous inhumanity, and the courage, hope, poetic and practical resistance of those had lived and died in that terrible time. I was also reminded how important it is to keep hope alive, even in the most desperate of circumstances, and to carry forward memory, so that light can continue to shine and triumph again in our world's persisting darkness. I was but one of a handful of people at the showing yesterday, and all but one other were older East European Australians. Yet the beautiful and poignant understated documentary, and accompanying CD of the songs from the ghetto, continue to share the story and lead to sanity for others too.

This work is timely, both for the Jewish community and for the wider global community as it endures further horrors of genocidal and ideological madness. As the last survivors of the Shoah dwindle, it is vital that their songs and stories are shared. A major theme of the documentary is indeed that of the third generation of ghetto survivors and it begins with a granddaughter returning to Israel for her grandfather's funeral. Like the Jewish children singing in Vilna today the ghetto songs, the affirmation of the later generations that 'we are here' is a powerful expression of hope and the reality of life surviving even abject and extraordinary death. For the experience that is related speaks both of what was and what is and will be. In the face of the ghetto's horror, and the daily encounter with death (close at hand or in the killing fields of the nearby Ponar forest), the Jewish community used theatre to keep the spirit alive. In this they were aided by remarkable people, such as Amroz Sutzkever. Probably the greatest Yiddish poet of the holocaust and one of the most outstanding poets of the whole 20th century, Sutzkever's words were both brilliant in their expression and amazingly strengthening amid the scarcely imagineable harrowing. Nor was he alone. One of the most powerful parts of the whole documentary is the song Mother, written by Chayele Posnanski after the murder of her mother. She herself also did not survive the war and this is the only legacy she left. Like Satzkever's work, the song acts as a means of transcendence, an affirmation of life in the midst of the almost unbearable grief of existence. Poetry is thus, like other arts, not just an essential expression but a necessity at the very heart of life. It becomes prayer beyond prayer. In Sutzkever's extraordinary poem and song 'Unter Dayne Vayse Shtern' it is indeed prayer itself: 'under your white stars/offer me your white hand/all my words are flowing teardrops/I would place them in your hand.' It is hope beyond the harrowing, beyond 'the murderous quiet'. At the end of the documentary, one survivor, Theodore, reflects that humanity still seems to want more of such tragedy, not yet having learned its lessons. Like the story and the songs, it is a sobering observation. Like the story and the songs however, it is not an expression of defeat and resignation but of centred humanity and continued hope. There is appropriate 'forgetfulness' in the story, for many survivors the only way to survive. Yet this is also subversive memory and a life-giving poetry of hope. |

AuthorJo Inkpin is an Anglican priest serving as Minister of Pitt St Uniting Church in Sydney, a trans woman, theologian & justice activist. These are some of my reflections on life, spirit, and the search for peace, justice & sustainable creation. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed