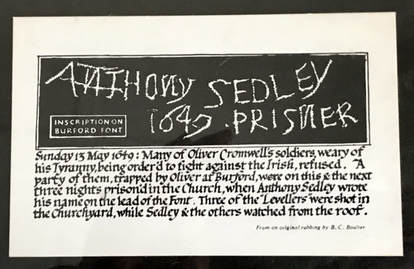

From my early childhood, I have always been engaged in exploring what liberty means. I grew up fascinated by history for that reason and it is not for nothing that the pictures over my office desk resonate with some of the mightiest of English struggles for liberty: a copy of the Magna Carta, photographs and records of female suffragists, and, most poignantly of all, a facsimile of the Leveller Anthony Sedley's scrawled protest on the font of Burford Church (see picture to the right). Such epic battles, mixed in as they often were with religious identity and aspiration, both challenge and inspire. They are in parts a record of gruesome hurts but also witness to the Christ-like 'courage to be', to re-imagine, and to 'turn the world upside down' Imagine then my frequent puzzlement and dismay, when some people, in comfortable places, speak about religious liberty as merely the right to hold and publicise curious opinions and practices or to protect privilege. Of course I would not wish to deny others the first of those things. Yet liberty is so much more...

0 Comments

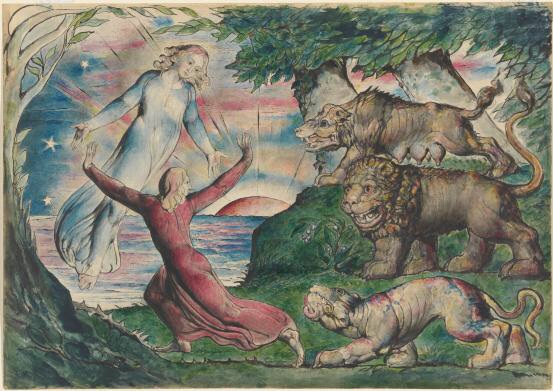

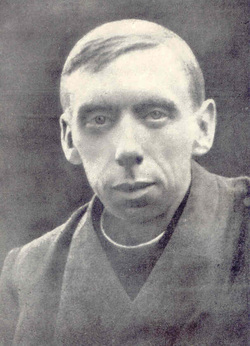

Toowoomba Preparatory School - now known as Toowoomba Anglican College and Preparatory School (TACAPS) - began in 1911 and has seen many changes and had many achievements over the years. It has certainly been a well loved Anglican school for so many who have passed through its doors. From an initial foundation of 17 students, it has grown as the only co-educational Anglican school in the Diocese of Brisbane west of the Great Dividing Range. Sitting picturesquely atop the Range, it indeed has a very beautiful series of buildings and resources and a delightful assembly of students and staff. It is currently however facing one of its biggest challenges as it transitions from what has essentially been a junior school to a full school covering ages from kindergarten to year 12. This also involves developing new outward-looking relationships with others. As an Anglican school located in the parish of St Luke, Toowoomba, this is an important concern for many of us in the wider church too. It is also an invitation for others to join in what is an encouraging spirit of faith in the future. For what above all impressed me in my most recent visit last week was the passion, imagination and practical pastoral and educational vision of the school, wonderfully embodied in its Head of School, Mr Simon Lees. This not only gave me confidence for the school's future but was also a witness to others to grasp the nettle of change, with all its demands and uncertainty. For a journey into the unknown can be unsettling for any well-established institution, even one with the past and present resources of TACAPS. It requires a genuine faith in the future and care and imagination to match. It is literally, as well as metaphorically, trusting in things unseen. For me, this was marvellously expressed both by the fledgling first-year students and staff of the inaugural year 8 and by their aptly named Inspiration Room. Would that every Christian body had an Inspiration Room! As our parish at this time seeks to discern its own 'mission action plan', part of which must involve developing closer links with TACAPS as part of our commitment to being One Church with One Mission, this is an encouragement and inspiration to us too. Can we all respond to the invitation to have faith in the future?  If William Blake had lived today, I suspect he would have had a field day. He would have thrived as an all-round artist in our multi-media age and he would have been a vital voice for visionary sanity in our blinded days. Such is my sense amid my deepened passion for Blake on visiting the current exhibition of some of his visual art in the National Gallery of Victoria this week. For, despite the strangeness of elements of his work, what we continue to discover in Blake is an astonishing wholeness of vision, mediated by word and image, poetry and politics, religion and the secular, all held together.. The NGV has a surprisingly large collection of Blake's watercolours, engravings and prints and the present exhibition is the first in fifteen years to showcase them. Not least this includes 36 of Blake's 106 portrayals of Dante's work, striking in their myth and meaning. It was a vivid demonstration of the importance of word and image in unity. Indeed I realised how much we often think of Blake as merely a poet and wordsmith (albeit such a great one), when his visual work is so central. He began his working life as an engraver and this was what brought him the bulk of his income, small though that remained throughout his life. His biography is certainly also a reminder of that other England which is frequently overlooked and underestimated. This is the England of struggle and solidarity, of nonconformist humanity and the very best kind of eccentricity. It is the England of Milton and Shelley, with whom, with contemporaries like Mary Wollstonecraft, Blake forms a blessed genealogy, imbued with radical and generous republican hope. Blake's vision is of a world in which Albion and Jerusalem are one: material and spiritual together, alive with grace and love. In the face of today's constraining functionalism, his is still such a liberating cry for freedom, and for imagination and not mere 'reason' as the source of life and joy. As he wrote, 'prisons are built with the stones of law, brothels with bricks of religion'. Instead, we need to cultivate the contemplative, being true visionaries of word and image, understanding and doing: ''To see a World in a Grain of Sand/And a Heaven in a Wild Flower/Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand/And Eternity in a n hour.' For, in a vision as necessary today as in his own day, and demonstrated in the various interwoven facets of his life and work, Blake was right: 'A Spirit and a Vision are not, as the modern philosophy supposes, a cloudy vapour, or a nothing: they are organised and minutely articulated beyond all that the mortal and perishing nature can produce.' Not for nothing have I had words of Blake above my office desk for several years: 'Imagination is evidence of the divine.'  It makes all the difference, John O'Donohue once said, whether you see God as an artist. Once you do, everything changes. For, as he observed so rightly, we have so over emphasised the will of God, and so devastatingly neglected the imagination of God, that we have deeply impoverished ourselves. For: Each of us is an artist of our days; the greater our integrity and awareness, the more original and creative our time will become. (in To Bless the Space Between Us: A Book of Blessings) I didn't used to regard myself as an artist. That is only for special people, I used to think, and you have to be very good at it. Now I know that that is bunkum. We are all artists. Some work with paint, clay, or other materials. Some with the human body and its expression. Others with music or words. Others shape places, communities, moments or people. For we are all made in the image of God, and the first divine blblical characteristic (read Genesis) is creativity: then, now and always. That is something I love about St Luke's church in Toowoomba. It comes marvelously alive when, at Carnival and at other much more ordinary times, it is clothed with the grace and creativity of God in human artistry. And it can happen every day, if we let it and embrace it...  For me, the church is therefore what a brave man once called 'an art school of divine majesty'. Think of that, or, better still, imagine that: feel it, and see what a difference it makes to your life and faith and that of others. What Fr George Tyrrell (see photo left) was trying to say is that being part of a religious tradition and community is like being part of an artistic tradition and community. There may be great 'masters' like Rembrandt who show the way. An artist may sit at their feet and learn and develop in that art school. For we do not make art by ourselves. That is an individualist fallacy. Yet there will come a time when every artist need to make this task their own. Perhaps they will even overthrow some of the foundational assumptions and shapes of their master: all however in the cause of deeper beauty, love and truth. Isn't that, said George Tyrrell, how faith evolves and expands? Tyrrell was a man of great courage. For, drawing on God's grace and the riches of the Church's tradition, he used his creative imagination, scholarly intelligence, pastoral sensitivity and deep religious learning to give new life to the Church of his day. Today many of his insights have been accepted, further critiqued and developed by Catholic and Protestants alike. However he was condemned by Pope Pius X, with other so-called Catholic Modernists, expelled from the Jesuit order, denied the sacraments, and finally excommunicated. He was not allowed a Catholic burial and was interred in an unmarked grave. A priest friend, Henri Bremond, who had the grace to make the sign of the cross over the grave, was himself, as a result, then suspended for a while. For being a religious artist is not always easy - just see what happened to Jesus. Yet being an artist, and part of an 'art school of divine majesty', is part of the gateway to resurrection: to greater and deeper life, beauty, truth and love, for us and for others. May the divine artist flourish in everyone. |

AuthorJo Inkpin is an Anglican priest serving as Minister of Pitt St Uniting Church in Sydney, a trans woman, theologian & justice activist. These are some of my reflections on life, spirit, and the search for peace, justice & sustainable creation. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed