Should any green ordinands (aka ministry formation students) ‘fall’, where do they go? I sent thankful video greetings across the globe this weekend to my best man, at my wedding, celebrating a significant birthday landmark - cheers Chris - and it set me reflecting on what has happened to my immediate generation of would-be clergy…

0 Comments

As we merge from the worst of the recent Omicron Covid-19 wave, it was a great joy and delight to host the ordination of Stuart Sutherland in Pitt Street Uniting Church by the International Fellowship of Metropolitan Community Churches, with other very good friends and Christian companions.

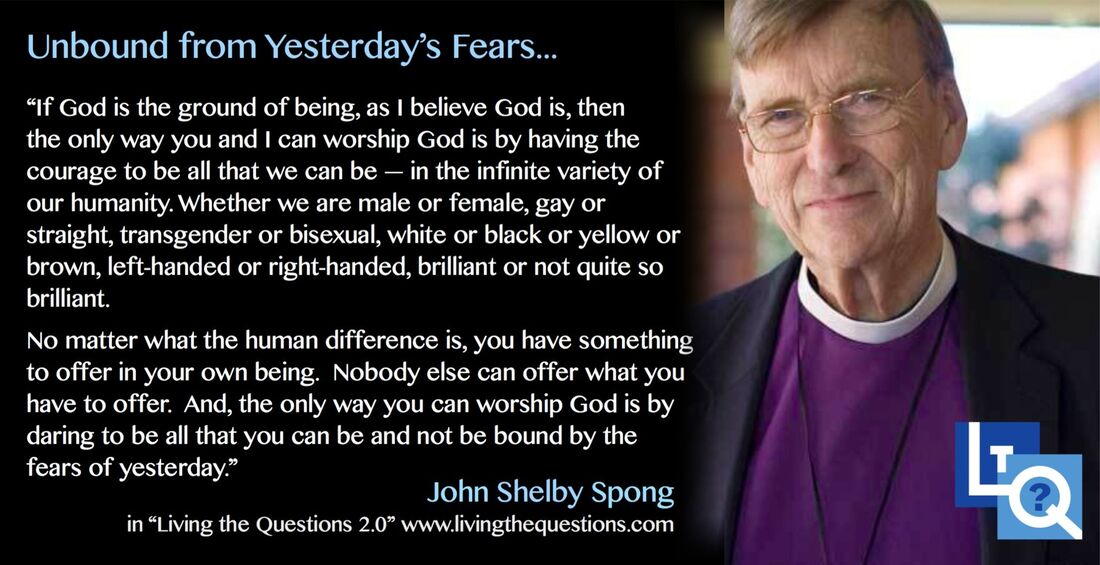

Dare to be indeed. The first time I heard Jack Spong speak was in October 1992 in Methodist Central Hall in London - at the launch of Elizabeth Stuart's then highly controversial landmark LGBT+ prayer book 'Daring to Speak Love's Name: A Gay and Lesbian Prayer Book'. They were historic and testing times. Two weeks later, after our long struggles, the Church of England would finally vote for women's ordination but opposition to queer people was so much more intense. I'd traveled down from Gateshead in England's north east for the occasion, and was one of 300 or so queer people and allies who shared in what was a powerful and moving show of solidarity titled ''Prayer, Protest, Politics: A Celebration of Who We Are and Our Relationships.'' The evening featured an informal blessing of queer relationships, prayers and recitation of a ''Declaration of Coming Out,'' as we danced, cried and hugged together. Helped not least by negative remarks by the then Archbishop of Canterbury, George Carey, SPCK, the intended publisher, had pulled the plug on the book. Thankfully however, Hamish Hamilton Ltd (part of Penguin) stepped in at the last minute and the book thus defiantly and joyfully came to birth (more on the story here). Whilst other Church leaders ran from the fray, or hid behind kindly but insufficent words, Bishop Spong stood on the stage that evening and shared his own commitment as true ally. Those kinds of actions matter. I'm grateful to him for many other ways in which he helped set people free from fears into new life. As much as as his words, such actions however really stay with me. In his death, as in his life, he continues to ask us, where are you when life and history is to be made and shown? Dare we continue to speak love's name when and where it is needed? #deedsnotwordsalone  First of all, may I acknowledge the traditional owners of this land and all First Nations people in this area. I also give thanks for this cathedral, so important to me in my own journey in recent years, and all who have helped develop the unfolding work of Christian feminism which we highlight tonight. In introducing and commending Mavis’ book, I am reminded of a number of things from the first wave of Christian feminism, which was the subject of my Ph.D. One is a famous quotation from the northern English working-class leader Ada Nield Chew: women’s advance, she used to say, ‘’tis a long row to hoe.’ What we do today, as Mavis encouraged in her book, is part of a continuing journey. The South African writer Olive Schreiner put it strikingly in one of her essays, which drew heavily on biblical imagery, and helped her become the ‘muse’ of first-wave Christian feminists. One of the Anglican suffragettes, Lady Constance Lytton, referred to this in her autobiographical account of the sufferings of female campaigners in prison. We were encouraged each night in Holloway, she recalled, by readings of Schreiner’s work, not least the story ‘Making a Track’. An allegory of women’s, and others’, struggles for justice, this described a long trail of the bodies of insects stretching over a long distance. These learn, as Olive Schreiner put it. to ‘take off the shoes of dependence’, to clothe themselves in ‘the garment of Truth,’ and to use ‘the staff of Reason’ when they are lost and cannot find a way. Eventually the track of bodies reaches the banks of a river to cross into a more spacious land of freedom, fording the river with the costly solidarity of their bodies. On the other side, there is room for more authentic life and expression. ‘But what of those who did not make it?’, asks one of the characters in the story, ‘those who were swept away by the current or did not even build the bridge with their bodies?’ ‘What of that?’, comes the reply, ‘they make a track to the water’s edge’ and ‘over that bridge, which shall be built with our bodies… the entire human race will pass.’ Mavis was one of those great Brisbane women who helped form the bridge of women’s ordination, and stepped over. Yet, as the exhibition of Anglican women’s history in this cathedral affirms, she would not have been able to do so without others who had made the track to the water’s edge. Vitally, she also knew that stepping over the bridge was not enough. Much more was needed. Some of that has been in evidence in recent years, including the first female bishop in this diocese. Yet Mavis was clear that such landmarks are insufficient without a much greater transformation. This is what she calls us to in her book Gender Balance. It seeks, and embodies, not an end but an encouragement to travel on. Indeed, for me it is a particular delight to see it published, for it represents a key part of the track – after the ordination of women - that was so difficult, and which is so easily ignored. If we are to travel on further, into fuller life and freedom for all, we need to see the whole track and learn from it. This is what Mavis’ book helps provide. We are diminished without it. Understandably, after the first ordinations of women, the movement which brought them about lost steam. Partly this was because so many wonderful women poured their hearts, faith and lives into parish and other ministries hitherto denied them. This brought much fruit but came at a cost from which we are still, I think, recovering. As a lay woman who had helped lead MOW locally, Mavis saw that. Gender Balance thus represents her perceptions of what more is needed on the track. She perceives the insidiousness of patriarchy and clericalism. She asks us to go deeper, to reconsider symbols and language, relationships and support. She also reminds us of the bigger vision of Christian feminism, so much larger than ecclesial offices or church facing concerns. Lift your gaze, she continues to challenge us. Renew the pathway and the purpose your forebears marked out, at the cost of their bodies, lives and faith struggles. Mavis thus recalls us to the promise of the 21st century in which we live and to a better Faith in which to live it. She outlines how the continued undervaluing of women is a major feature of what she calls ‘Christianity’s Credibility Crisis’. Indeed, she shows how women and women’s experience is devalued in aspects of our Faith and how dissent is resisted by entrenched attitudes and structures. At the heart of this is what she calls ‘The Embodiment Problem’, even though women carry with them connections and resources which can bring new life. She affirms that women’s theology and spiritual experience can thus help to renew the expression and work of the gospel, providing health in so many other fields also. Gender Balance is not entirely complete as a vision of Christian feminism for today. For there are some new elements recently which have entered the journey, which can make us stumble or enrich us. Mavis does not really speak for example of the rise of sexual and gender diversity, which have made the track more complex and enlivening. She also wrote at a time before the full rise of recent phenomena of terrorism and anti-terrorism, and the resurgence of populism and authoritarianism in politics and religion. Yet, even in the face of such factors, Mavis reminds us in the book of other features which we have neglected. Not least, particularly at the end of this Week of Prayer for Christian Unity, is the value she rightly gives to solidarity and co-working across our denominational and national boundaries. She thus draws widely on the work of Catholic and other theologians, and on ecumenical connections, not least the inspiration that was the Ecumenical Decade of Churches in Solidarity with Women. What an idea that would be to see again! What a difference it makes when women and others make fresh linkages together, as the #MeToo movement and Marches for Justice have shown recently – the wider and deeper agenda of liberation is not lost, but renewed. I sadly only met Mavis in person once: when she came to my home, on the St Francis College site, to talk with some of our students and others about the ordination of women struggle, its legacy and learnings, and the need for the continuing journey. Yet I feel strongly that, if she were here today, she would be warmly encouraging us to take the next steps on the track – and this, she indeed does today through this book, distilling some of her lively insight, informed reading and personal wisdom, continuing to challenge us (as the self-confessed ‘Anglican spiritual guerilla’ she was) and willing us on. Do take up Mavis’ book, learn and inwardly digest, and, inspired by her spirit, and that of all who have gone before us and made the path to the water’s edge, build the next bridge and help others cross over. For like Mavis, we either help to make our own history, or are condemned to be victims of it.  I’ve been happily reminded recently that, in moving to share ministry with Pitt St Uniting Church in Sydney, I follow in a few footsteps of one of my great heroes, Maude Royden. A leading first wave feminist, internationalist and peace advocate, among many other things, Maude started the Anglican ordination of women campaign. Prevented from preaching, she then became an assistant minister at the prominent City Temple (Congregationalist church) and was also the first Anglican woman to lead a church (an ecumenical fellowship she founded at The Guildhouse, also in London). In her worldwide speaker tours, she drew huge attention, with massive numbers - including packing Pitt St way over capacity, with lines and lines of people locked out down the street (a similar feature repeated at the one Anglican Church in Sydney which had the courage to invite her). Laura Rademaker provides a very good reflection on Maude’s impact on Australia (particularly in the challenge she was to existing ideas of sex and women) - check out ‘Sex in the pulpit: the feminist preacher for Aussie flappers’ on the Australian Women’s History Network webpage, and her fuller article ‘Religion for the Modern Girl’’ in Australian Feminist Studies (2016)). My own online tribute to Maude is in the link here, picking up on one of my favourite passages in Maude’s writings, where she speaks of ‘the great adventure’ of Christ and faith, contrasting so starkly with the deathly ‘activity’ which often passes for life in churches. To follow Christ is the invitation, she said, but: “Would it be safe? No, of course it would not be safe… we are afraid of such risks, afraid of such a terrible victory (as Christ’s)… we treat the Church as one long accustomed to ill-health. Do not open the window! Do not bang the door! You cannot take risks with the invalid. Step lightly, speak softly, at any moment the poor thing might die!” We, like Maude, can do do much better - in our lives, our world, and even in churches :-) Wow! It was quite a roller-coaster ride of a farewell Eucharist last Sunday - with such wonderful people at Milton Anglicans that it is so hard to leave behind...

Tomorrow is the 30th anniversary of my ordination as priest, so it seems appropriate to break what has been a (initially unintentional) five month blog fast. For as I look back and around today, reflecting on my life and vocational journey, it seems new beginnings are certainly in the air. For some time I have felt myself in a watershed period and this is certainly true of 2017 so far. Today I fly back from Vancouver, at the end of a short stay in Canada en route back from the UK. For at the beginning of June my parents marked their 60th wedding anniversary. My wife and I therefore coupled being there with a series of different work and research engagements which will hopefully bear much fruit for us and others in the next few months and years to come. As we stood awaiting our suitcases at Heathrow at the very end of May, we also received news of the birth of our first grandchild. Symbolically it was a powerful expression of new phases of life into which we, and many people and interests we share, have entered. In the next few weeks I hope to share some important aspects of changes which have opened up for us, pondering a little on the significant shifts which have taken place for us so far this year (new city, new house, new jobs, new work roles, new family roles, new relationships, new understandings of ourselves etc) and those to come. However, on the eve of my priestly ordination anniversary, it is enough to reflect briefly on a visit to the St Brigid's Community gathering at Christ Church Anglican cathedral in Vancouver last Sunday. St Brigid's is a three year old emerging church initiative, with a particular affirmation of diversity (not least of LGBTI+ people) and is apart of the cathedral's developing ministry and mission. It marked the feast of St Peter and St Paul (my ordination festival) on Sunday and I was greatly moved by the shifts of 30 years. At that time, in St Paul's cathedral in London, all was done in the style of high Anglican papalism, with a presiding bishop who shortly afterwards converted to Roman Catholicism - out of horror of female ordination - and who insisted on determined Anglo-Catholic clerical elements, including a concelebration of new priests which excluded some of different Anglican tradition. At St Brigid's, whilst surprisingly faithful to today's liturgical expectations, it was very different. The female priest presided engagingly, inviting all to reflect and contribute together on their response to the texts and themes of the day, and to gather as one around the eucharistic table. Transgender, as well as other LGBTI+ people, shared deep Christian insights, speaking from their own faith experience, embodying the new voice and confidence gradually being found even (slowly and sometimes agonisingly) in the churches. For me, it was a beautiful affirmation of so much that I have prayed and worked for over the past 30 years, and a wonderful timely encouragement to new steps into the future. Sometimes God seems particularly close, especially at times of threshold and transformation. Feeling renewed in my vocation, may the journey of grace continue for us all. |

AuthorJo Inkpin is an Anglican priest serving as Minister of Pitt St Uniting Church in Sydney, a trans woman, theologian & justice activist. These are some of my reflections on life, spirit, and the search for peace, justice & sustainable creation. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed