|

It is a bit of a tricky time for some of us right now with the tsunami of royalist outpourings - not least those like me, who, in Australia, also struggle with general Australian assumptions that, being English, we must therefore be monarchists. I’ve been trying to avoid the subject - and especially the media frenzy - but I guess, as I keep being asked about it, I’m trying to find a kind but honest answer. So I hope this doesn’t offend anyone, but other things should also be said...

0 Comments

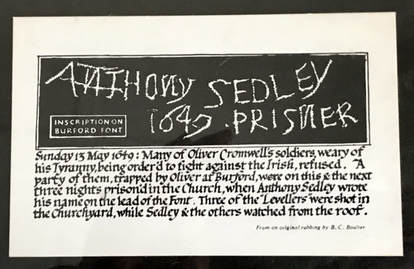

From my early childhood, I have always been engaged in exploring what liberty means. I grew up fascinated by history for that reason and it is not for nothing that the pictures over my office desk resonate with some of the mightiest of English struggles for liberty: a copy of the Magna Carta, photographs and records of female suffragists, and, most poignantly of all, a facsimile of the Leveller Anthony Sedley's scrawled protest on the font of Burford Church (see picture to the right). Such epic battles, mixed in as they often were with religious identity and aspiration, both challenge and inspire. They are in parts a record of gruesome hurts but also witness to the Christ-like 'courage to be', to re-imagine, and to 'turn the world upside down' Imagine then my frequent puzzlement and dismay, when some people, in comfortable places, speak about religious liberty as merely the right to hold and publicise curious opinions and practices or to protect privilege. Of course I would not wish to deny others the first of those things. Yet liberty is so much more...  Giving thanks today again for my ‘first love’, and for the wonderful fellow devotees and mentors who shared with me her joy and pain and subversive power of transformation. I am challenged too to return to the task. Is there a ‘history gene’? There are days when I wonder: when I meet people who have little or no sense of the past, of the human story, of the beauty and siren song of Clio, the muse of history. Like someone who is musically, artistically, or religiously deaf or blind, they can function, sometimes much better than I. Perhaps they are indeed in some way fortunate, immune from Clio’s mischief and agonies. Yet they lack the ecstasy of her communion. They have little or no ex-stasis – no place to stand – outside the purely immediate, the merely commonplace, the simplistic assumptions of the present, so deeply shaped though these are by the past and its perspectives. They seem hidebound, for they are timebound. For history may indeed have created walls in which we humans are imprisoned. Yet the study of history can be a door to our release. Like a wondrous Tardis, we are whisked away within it to other places and other people, to the possibilities of fresh perspectives and to passionate, patient, peacemaking. As C. S. Lewis once wrote: Most of all, perhaps, we need intimate knowledge of the past. Not that the past has any magic about it, but because we cannot study the future, and yet need something to set against the present, to remind us that the basic assumptions have been quite different in different periods and that much which seems certain to the uneducated is merely temporary fashion… the scholar has lived in many times and is therefore in some degree immune from the great cataract of nonsense that pours from the press and the microphone of his own age... Love this creative, and appropriately fresh democratic, way of marking Magna Carta...  For several years I have had a copy of Magna Carta on my living room wall. An odd thing this may seem to many. It seemed a waste however to have it rolled up in a cylinder and it is a reminder to me, both of my personal history and origins and also of the continuing challenges to seek and nurture liberty. For I grew up, for most of my childhood and youth, near Lincoln, whose Cathedral owns one of the originals from 2015, now located in a permanent exhibition in Lincoln Castle. I also treasure a visit a few years ago to Runnymede, the site of the Magna Carta agreement, close by to where my sister currently lives. Above all, Magna Carta touches on so many aspects both of my historical interests and political concerns. In this 800th anniversary year of Magna Carta, it was therefore wonderful yesterday to be able to visit the Magna Carta: Law, Liberty, Legacy exhibition in the British Library. What most, pleasantly, surprised me in the exhibition were the series of historical documents, books and other artefacts from across the centuries. These were great to see, as well as refreshment to the European part of my soul which, much as I love Australia, sometimes struggles with the lack of appreciation down under of the highly diverse layers of history. Perhaps Europeans can sometimes themselves be trapped in such layers, and ignore the much more than human immensities of life, and such gifts as those of the oldest continuous civilisation on Earth, found in Australia. Yet, for me at least, to delve back into my own inheritance of history is to feel a renewed sense of intimate connection, wonder and empowerment. The Magna Carta exhibition, as its subtitle suggests, seeks to place Magna Carta in the great traditions - I would say always uncertain struggles - of law and liberty, and their legacy, particularly in Anglo-Saxon shaped countries. Lines of influence are drawn across time: including to English resistance to 17th century tyranny, 18th and 19th century radicalism, American affirmations of liberties, and 20th century declarations of rights (including by the UN and Nelson Mandela). Rather than being a legal instrument of tight principles, it is perhaps best viewed as a continually revered tool against oppression and a potent inspiration to 'maintain the rage'. Unlike other approaches, such as French and Russian, this Anglo-Saxon pathway to liberty looks not so much to radical logic or abstract ideals as to the precedents and pragmatic practices of the past, albeit often mythopoeic visions and creations out of the contexts of later times. Only three articles of Magna Carta are still UK statutes but it still has the power to shape our past and future. One remaining article is the first in Magna Carta: affirming the liberty of the English Church in the face of monarchical (or, by implication, other) domination. This reflects the work of the then Archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langton, a key force for reconciliation and (limited) justice in 1215. Significantly however, the then Pope disagreed, dismissing Magna Carta to the dustbin of history in his papal bull which followed. Ironically Sir Thomas More did not agree later, appealing to Magna Carta against king and for the papacy. Perhaps Christian leaders, in our own age, would do well to renew that spirit of Magna Carta, whilst seeing its insistence on liberty as something not for a special few but for all, whoever and whatever we are. The barons, like the then king and Pope, of 1215 would have been horrified to see their ideas of liberty so extended. Blind or forgetful to the inspirations and horrors of history though we may often be, we 21st century people really do not have the luxury.  The other day at home I found a wonderful book, related to my doctoral studies, which i had not really looked at properly. It is entitled England's Voice of Freedom: An Anthology of Liberty. First published in 1929, it was edited by the radical journalist Henry W. Nevinson, an active participant, among other things, in the women's suffrage movement. He was, unhappily, married to Margaret Wynne Nevinson, a leading (Anglican) Christian feminist and one of my personal heroines. Not surprisingly, there are a number of first wave feminist entries in the book, among a treasury of inspirational texts on liberty. Nevinson's book is a timely reminder, in this 800th anniversary year of Magna Carta, of the amazingly deep, delightfully varied, and incorrigibly ingrained spirit of liberty in the history and very spirit of England. Of course there are other trends and spirits, not least: the arrogance, authoritarianism, and class-ridden contempt of many English so-called 'elites' down the centuries; an occasionally recurring mean and miserly insularity which can sap the soul of English delight and generosity; and the brutality and coarse violence which has often been close to the surface at home and, sadly, exported abroad. Living away from the land of my birth, I am well aware both of those failings and the danger of romanticising. All great peoples also have inspiring words and lived examples of liberty. Yet, for all that, there is something in the English heritage which, as Nevinson put it, is 'peculiarly English in the ideas of freedom' that have been passed down: 'something that appeals very intimately to the English man or woman born and bred... and nurtured unconsciously upon her ancient traditions as I have been'. Perhaps, at a distance, those unconscious elements can also become a little clearer?... |

AuthorJo Inkpin is an Anglican priest serving as Minister of Pitt St Uniting Church in Sydney, a trans woman, theologian & justice activist. These are some of my reflections on life, spirit, and the search for peace, justice & sustainable creation. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed