When some people question me about religion and violence, and especially Islamist related violence, I often think and talk to them about Azim Khamisa, one of the most inspiring people I have ever met. A successful international financier and Sufi Muslim, Azim's life was turned upside down when his twenty year old son Tariq was shot and killed, for the price of the pizza he was delivering. Yet, out of the midst of his terrible anguish, an amazing compassion, rather than commitment to vengeance, arose. Azim came to realise, as he puts it, that there were 'victims at both ends of the gun' that killed his son, and this spirit-led understanding drove him to contact the family of his son's killer (whom he then later met and has lobbied for) and to commit his life to sharing the power of forgiveness, particularly among millions of young people vulnerable to gang culture and other pathways to violence. His mission is especially embodied in the Tariq Khamissa Foundation but has also been exercised internationally through books and other communications tools and events of various kinds (including his own website found by clicking here). When I think of the message and example of Jesus, Azim is an amazing contemporary model. A little of his story can be found in this video clip:

0 Comments

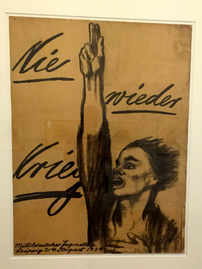

As we let go of one year and begin another, it is good to give thanks for all that has been and to open ourselves with fresh hope and compassion to the future. The two things are connected. My final visit in Berlin this year for example was a way of paying tribute both to past inspiration and to its continuing living 'subversive memory'. For in the Friedrichsfelde Central Cemetery are the graves of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, among others commemorated at this Memorial to the Socialists. Other parts of the cemetery also house the graves of creative people, including the amazing artist Kathe Kollwitz. In some ways it is a sad place, not only as cemeteries typically can be, but also because of the failure of much of the vision and hard work of those buried there. Yet as the main commemorative stone has it Die Toten mahnen uns (The dead remind us), at their best, prompting us to renewing life and love. My politics have never been quite those of Liebknecht and Luxemburg, but I have always admired their commitment to a better world, sacrificial solidarity with the poor and outcast, intelligence and vision. To lay a flower on each of their graves was thus for me to express a debt of gratitude and to pledge with others to renew their work in a new way. My guess is that, in Rosa Luxemburg's case for sure, if they had not been murdered by the Freikorps in Berlin in 1919, their work would have been betrayed by others, including those indeed like one or two of the East German communist party apparatchiks buried alongside them. For being of Polish birth and Jewish extraction, and a feminist socialist with a physical disability and a brilliant independent mind, Rosa was always an uncomfortable figure to so many. Her most famous words sum this up and remain a powerful challenge and inspiration, whatever group(s) we belong to: Freedom only for the supporters of the government, only for the members of a party – however numerous they may be – is no freedom at all. Freedom is always the freedom of the dissenter. Not because of the fanaticism of "justice", but rather because all that is instructive, wholesome, and purifying in political freedom depends on this essential characteristic, and its effects cease to work when "freedom" becomes a privilege. For those words alone my pilgrimage would have been worthwhile, but there is much more. For to me, Rosa stands for many more, living and dead, who continue to believe in, inspire, and work, for another kind of world, however we imagine what Christians like me call 'the kingdom of God'. And so, for the coming year, in the words of the anarchist poet Pietro Gori, in Primo Maggio, written in 1890: Green May of humankind, Give your courage and your faith to our hearts. Give flowers to the rebels who failed Their sight fixed upon the break of dawn, To the bold rebel who fights and works To the far-seeing poet who sings and dies.  One of my main highlights of visiting Berlin this year was the Kathe Kollwitz museum. An artistic genius, Kollwitz' life and work are inspiring examples of the German soul. She was an outstanding pioneer for women, with a profound social conscience and identity. A committed socialist and pacifist, who shared the life of the poor with her doctor husband in Berlin's struggles, not for nothing was she commissioned to create a powerful memorial to the murdered Karl Liebknecht. Tragically, her compassion for the victims of war and oppression and the strength of poor women, especially mothers, was embodied in her own sufferings over the loss of her son in the first world war. Removed from her leading role in German arts and culture by the Nazis, she was eventually evacuated from Berlin in 1943 as foreign bombs wreaked violence, including, soon, the destruction of her own family apartment with its photographs and mementos of loved ones. A week later her son's home was also destroyed during a bombing raid. Kollwitz tellingly wrote in her journal: "every war already carries within it the war which will answer it. Every war is answered by a new war, until everything, everything is smashed... That is why I am so wholeheartedly for a radical end to this madness, and why my only hope is in a world socialism... Pacifism simply is not a matter of calm looking on; it is work, hard work." She died in 1945, 16 days before the end of the Second World War. Yet her transcendent art and inspiring hope, in and beyond suffering. lives on.  After the recent bombings in Paris, our Toowoomba Gooodwill Committee leadership decided to hold a gathering to bring together community leaders to strengthen our social cohesion and resilience. Held at the University of Southern Queensland this was well attended, facilitated by Professor Michael Cuthill and expert in research on social cohesion. Speakers also included the Mayor of Toowoomba Cllr Paul Antonio, Inspector Mike Curtin from Queensland Police Service, Venerable Wu Ping from Pure Land Learning College, Professor Ken Udas from USQ, and university student Sophie Ryan. Bishop Cameron Venables also led an engaging question and answer session with the panel of speakers and contributions from the floor - not least a several positive contributions from members of the Toowoomba Muslim community. Key themes included positivity, whole community engagement, valuing diversity, partnership building, leadership into action, open and truthful education, and acknowledgement of the need to read sacred scriptures and traditions in context and with a deep spirit of love and humanity, acknowledging potential 'texts of terror'. For my own introductory words as Goodwill chairperson click below on read more...  It was a delight yesterday to see the film Holding the Man with one of my most lovely, compassionate and Spirit-filled gay friends. Based on the poignant 1995 memoir of Tim Conigrave, Holding the Man (a resonant expression drawn from Australian Rules Football) tells the story of the love and life he shared from schooldays with John Caleo, including the struggles they faced with others and their tragic early deaths from AIDS-related illnesses. Adapted by Tommy Murphy in 2006, Holding the Man became one of the most successful of recent Australian stage productions. This film version will hopefully widen the audience much further, honouring Tim and John by increasing light and understanding and strengthening our human solidarity against all kinds of sexual and gendered oppressions. The film is certainly also 'a story of a generation'. From a personal point of view, as an exact contemporary of Tim and John (albeit on the other side of the world), I was indeed touched by remembrances of my own school days, university experiences, and early adult life, especially of wonderful gay and lesbian friends who also endured much pain (including some even to shocking early deaths) whilst vibrantly helping to transform our inherited climate of fear and repression. I also recalled my days as a young priest in London in the 1980s as the horror of the AIDS crisis broke upon so many, together with the horribly fumbled, generally fear-filled and, occasionally, fabulous response of Christians, as church bodies and individuals. How far have we come? In many ways, we have traveled a long way, even in Christian circles. Yet only a few days ago the New South Wales Government banned the showing in schools of the film Gayby Baby, which offers the opportunity to enter into the experiences of children growing up in lesbian and gay families. All credit therefore to Dendy Newtown for screening Gayby Baby at this time, to encourage others to enlarge understanding and provide public pressure upon uncertain authorities. Indeed, as we bought tickets for Holding the Man, my friend observed to the young cashier that he had had to travel from the Central Coast to find the nearest screening. 'How sad', in this day and age', she replied, 'that cinemas everywhere aren't showing it.' For all the gorgeous steps taken, we are still very much on the journey of compassion and solidarity, never mind of celebration. Indeed, alongside admiration for so many like Tim Conigrave and John Caleo, I was left yesterday with deep sadness, and renewed frustration and anger, at the slowness, and sometimes sheer reaction, of so many Christians fully to love their sexual selves, so many of their 'neighbours', and their God of infinite compassion and creative diversity. In the context of my generation, the negative responses of Church authorities and Christian parents to Tim and John's love was more understandable, though no less shocking and stabbing to the very heart. I rejoice in those, across the world and from so many Christian traditions, who are seeking to walk a different pathway, centred on a Christ of a very different yet authentically biblical hue. Compared to the wider western world however, and even the attitudes of the bulk of our own church membership, I fear the institutional church is still a very long way from where we should be. As Aussie Rules would have it, if we are not, in different ways, 'holding the man', then we are so often either not even on the paddock, or 'holding the ball' of a bygone generation. May we be kissed afresh with peace, joy and understanding.  my short address from the inter-religious panel of which I was a part at the UNESCO forum last week... Amitofu - salaam alaikum - shalom - g'day... I would like to share a special prayer - one which has been of great value to churches across the world, who together, through bodies such as the World Council of Churches, have sought intentionally, throughout this 21st century, to address violence and its causes. There are 4 elements to this prayer. These, I believe, help to sum up and focus Christian understandings of peacemaking: 4 elements to which, of course, we need to add another, namely, repentance (understood as saying sorry for our own parts in the violence of the world - and what others have done in our name: the name of our religion, or our country, or our ethnic or other group.) This is presupposed, for without repentance - without a profound change of heart - we cannot be free. The 4 elements of my prayer today help us seek this repentance or change of heart, as they are elements which are similarly deeply grounded in the Christian tradition but which are also accessible to all, to people of other faiths and none - and what we have heard earlier from Madagascar, for example has reflected that. The four key elements of this change of heart are: Firstly, Truth - because without truth we can never deal with things properly. Now of course Truth can be uncomfortable to face up to - like the truth about the violence inflicted in Australia in the past on our Indigenous peoples, or the truth of facing up to the violence of what has caused war and violence elsewhere, and continues to do so. Yet without truth there can be no reconciliation and no real healing - we are always likely to be violent again. As Jesus said - 'the truth will set you free'. Secondly, Justice - for without Justice there can be no real peace - as the biblical tradition has it, peace and justice belong intimately together: as the Psalmist puts it (Psalm 85.10) justice and peace must kiss one another for live to triumph. Or, as Pope Francis has reminded us, "without a solution to the problems of (today's refugees and) the (global) poor, we cannot resolve the problems of the world.' Thirdly, Compassion - for Compassion is, for Christians, the heart of God, and embodied in Jesus Christ. Until we have a heart for one another - until we start to share one heart, as some Indigenous peoples say, then we will always be broken people and a broken world. Until then there is a part of our own heart missing. We have to seek grace to cultivate kindness and mercy and their power to transform us and our world. Fourthly, Courage - for ourage is required to take risks for peace, justice and compassion. This is the courage of Jesus even to risk death in the hope of a better world and in the assurance that nothing can ever destroy the ultimate reality of life - the love of God - which can transform all that evil throws against it. For making peace comes at a cost but it is the path to renewal, or, as Christians put it, redemption. All of these things - truth, justice, compassion and courage - are crucial as part of our education for peace and a repentant, or transformed, heart and world. So let me therefore share this prayer of blessing: May God bless us with discomfort at easy answers, half-truths, superficial relationships, so that we will live deep within our hearts. May God bless us with anger at injustice, oppression and exploitation of people, so that we will work for justice, equity and peace. May God bless us with tears to shed for those who suffer from pain, rejection, starvation and war, so that we will reach out our hands to comfort them and change their pain to joy. And may God bless us with the foolishness to think that we can make a difference in the world, so that we will do the things which others tell us cannot be done. In Jesus Name, Amen.  Laying the foundations of a labyrinth at St Luke’s has been a beautiful symbol of our parish journey together. For we are named after someone – St Luke – who wrote the Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles to encourage us to see our life and faith as a journey into the heart of God and a journey into deeper relationship with all those around us. Like the first disciples on the Emmaus Road, we are called to experience God in Jesus Christ as we travel with our parish vision: to be more deeply ‘focused in Christ, joyful and inclusive, compassionate in witness’. Over the last few months we have been praying and reflecting together about the next steps we should take. It has been a very positive experience. For we have begun to discover new pathways building on our current strengths and shared Christian traditions. We have identified a MAP (short for Mission Action Plan) which we hope and trust will help us walk forward together over the next 3 years. Unlike the final stage of the labyrinth, it will not be fixed in stone. Some things will work. Some things will not. Other surprises will come our way. Yet our MAP will help us from straying from the pathway, helping us better attention to God’s love among us. in both our inward and outward looking journeys. There are six aspects to our MAP, like the six petals at the centre of our labyrinth. By far the highest priority identified by members of the parish is developing our ministry with younger people, children & families (including seeking a new paid member of staff to guide and support us). Alongside this is a second priority of engaging with the new Pilgrim course – for existing and new members of our parish to grow as Christians. Thirdly, we particularly seek to develop a growing sense of the St Luke’s site as a, cathedral like, Minster for our city: as an accessible place of prayer for all (‘focused in Christ’), an open meeting place for people of different backgrounds (‘joyful and inclusive’), and a lively place to explore and bring together ancient and contemporary understandings of life, truth, justice and beauty (‘compassionate in witness’) – ‘in the heart of the City, in the heart of God’. May God bless us therefore as travel on. |

AuthorJo Inkpin is an Anglican priest serving as Minister of Pitt St Uniting Church in Sydney, a trans woman, theologian & justice activist. These are some of my reflections on life, spirit, and the search for peace, justice & sustainable creation. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed