|

Red Dragonflies - naturally - are my choice of earrings for Fr Peter Maher's funeral today (particularly, so close to the Trans Day of Remembrance, as I remember the solidarity and hope Peter offered myself and other dragonfly people).

Red dragonflies especially can be rare to view, and very special (like brilliant loving priests) when the opportunity comes along. Yet, interestingly, they often appear to people surrounding life episodes of loss and death. For the dragonfly is a symbol of go-between people, winged priests of transformation. Death is after all the polarity of Life, and dragonflies help hold together the paradoxes of death in life and life, and eternal love, in death. In Japan the dragonfly is considered to be very sacred and symbols of transition. Red dragonflies appear most often there at the end of summer with the message that autumn is coming. A beautiful Haiku poem reads,” That the autumn season has begun is decided by the appearance of the red dragonfly.” The Japanese embrace the dragonfly as a symbol of courage, strength and happiness while some Native Americans speak of the dragonfly as bringing a time of rejuvenation after a long period of trials and hardship. Indeed they have traditionally perceived dragonflies as the “souls of the dead” - so a dragonfly visitation around a loved one’s death could well signify the loved one’s soul taking form in the spirit of dragonfly. It offers the assurance their soul is free. Fly wonderfully Peter in perfect light - just as you helped we others find their wings and reflect that light

0 Comments

I’ve always so loved this song (see below) - though it always makes me cry - and it, above all, with some others, has accompanied me in the last few weeks. The tender, lyrical and even elegiac, tone fits my mood as I prepare to leave England, maybe never to return, or certainly never with so many of the deep intimate connections of parents, home,and particular place which have so shaped me. Laura Marling wrote this at 18 and says she always feels about 8 years old when she sings it - I know the feeling just in listening . It’s about childhood memories (one in particular) and the ones who created them and about the particularity of place in this extraordinary land which I, like Laura, love so very very much, and from all of which separation is so very poignant. There hasn’t been any literal snow on my winter’s journey but enough in other ways - yet the warmth of love persists, like a beautiful garment in the cold… “You were so smart then In your jacket and coat. My softest red scarf was warming your throat. Winter was on us, At the end of my nose, But I never love England more than when covered in snow.” It was a deeply poignant yet beautiful Midnight Mass tonight in St Thomas' Church in Market Rasen. I had indeed had a yearning for one more such communion in the cold and dark and the depths of the symbolism and mystery it reflects - but not for years to come and not like this. The nave altar stood precisely where my parents’ coffins had been just two days before, the mood and singing was subdued by masks and the pandemic, numbers reduced and the liturgy unexuberant. Yet the magic, the miracle, persists - light in the very darkness, glory in the mire and sorrow, enfleshed spirit in our mixed up midst - and eucharistic participation on this, of all occasions, remains so truly special.

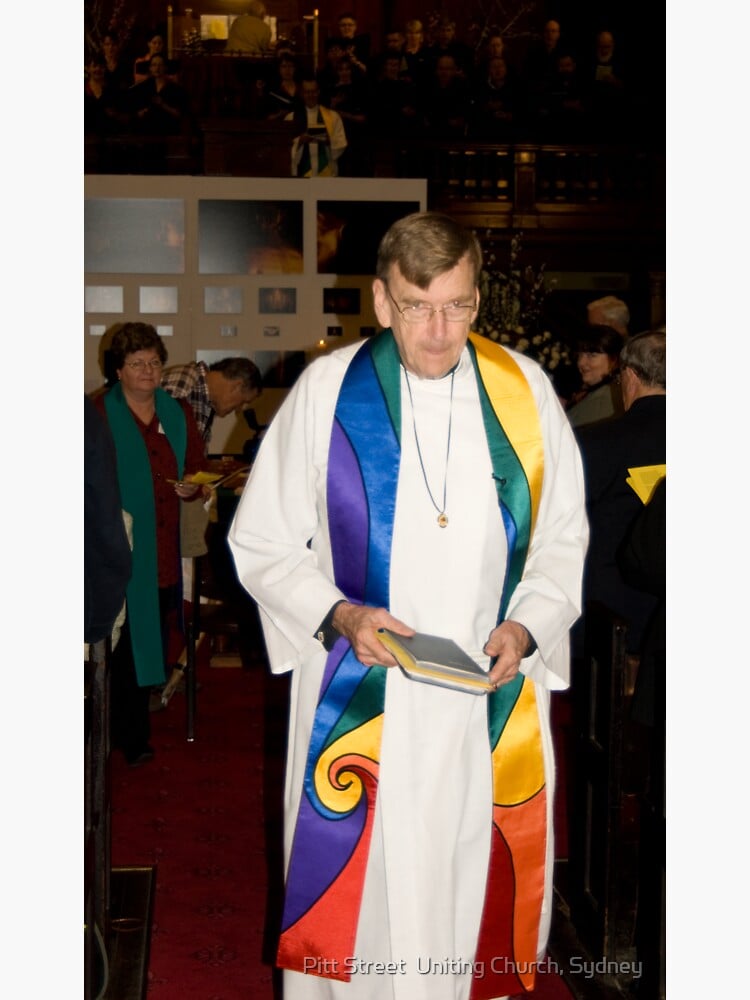

It was hard to move away into the night, for the last time to leave the church of my childhood and early formation, to step along the pathway into the marketplace one more time. The main street seemed even more deserted than ever as I made my return - even the wandering drunk had been spirited away. Walking the last part in silent darkness between the two cemeteries for the final time brought back the fullness of so many memories as well as profound emptiness and grief. For in the depths of our factual and metaphorical winters love can be reborn - just as a new dawn broke after the winter solstice on the morning of my parents’ funeral. T.S.Eliot was partly right. ‘A cold coming’ it has indeed been - ‘just the worst time of year for a journey… the very dead of winter’, even without the Omicron wave and renewed distance and desolation - but we do not need to be ‘glad of another death.’ Birth, life and love happens always - divinity in the vulnerability of our flesh: Incarnation in our dark. As Minister of Pitt Street Uniting Church in Sydney, it is a great joy and encouragement to stand in a powerful lineage of prophetic ministry. The more I come to know, the more I appreciate its vital significance to Sydney, and the wider world, in providing light, inspiration and hospitality to so many. As a community Pitt Street Uniting Church mourns the recent loss of Bishop Spong from our lives in this world, but rejoices in what he shared with us and so many others. We give thanks that we were able to offer a space for him to share God's love even when others were sometimes so hostile. Here above is a photo of the old Pitt Street Uniting Church's celebratory 'Bishop John Shelby Spong Greeting Card'!

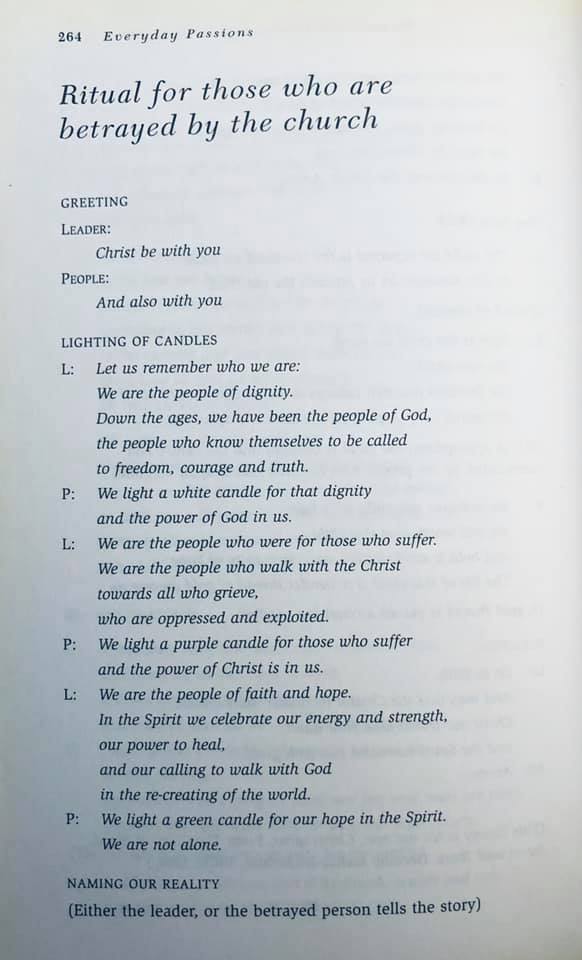

(we still rejoice to wear that stole too :-) )  It is funny how certain books jump out at you at particular times - and this one (Everyday Passions: A Conversation on Living) leapt at me today as I reflected on All Saints and the communion of the just/justified. For the author, Dorothy McRae-McMahon, has always been incredibly high on my list of Australian Christian heroes and this liturgy (the first page below) seems particularly appropriate right now. I’ve only met Dorothy in person once - sharing a platform in the Blue Mountains a number of years ago - and she seemed quite surprised then when I said she had been such an inspiration to me. She shared her wisdom in a NSW ecumenical project on prayer I once organised too (albeit she was then too ill to attend the key event in Sydney) and my involvement of her brought swift reaction from Sydney Anglican leadership - evidently they felt prayer was thereby made invalid, and ‘no Sydney Anglican will be part of the project if Dorothy McRae-McMahon is involved’ (as it happens, as on a number of other things, they proved wrong on that!). All of that kind of thing most certainly shouldn’t dent our courage for love and living truthfully. For as Dorothy wrote in this book (in the chapter ‘Living Life Under Attack’): ‘I would never choose to live under attack, but I will never regret living in ways which sometimes make it almost inevitable... To live in a way that produces attack in order to live more truly (as against choosing martyrdom) is to live with passion.’ The book ends with Marge Piercy’s poem ‘For Strong Women’ and Dorothy’s final words: ‘Living is, indeed, an everyday passion and “strong is what we make each other”’. With blessings and solidarity to those saints who live into wholeness and inspire others this All Saints-tide.  Jesus may have come that we ‘may have life and life in all its fullness’ (John 10.10b) but Christians frequently do a good job of seeking scarcity and restriction instead! Contemplating the sorry state of religion in many places it is not hard to see some common threads of resistance to Christ’s gospel of Abundance. It is a major reason for the rejection of Christianity among many. For the Church as a whole often clings so powerfully to prioritising reflection on death and sin above life and empowerment. This is particularly disastrous and objectionable for those, like LGBTI+ people, who have been held captive for so long by deathly categories of thought and sinful oppression. Rightly they seek life, and life in all its fullness. Asking for bread from churches however all too often results only in gifts of stone. In some ways individual Christians, and the Church in general, can often therefore appear like Ophelia in Bob Dylan’s famous ‘Desolation Row’: Ophelia, she's 'neath the window for her I feel so afraid On her twenty-second birthday she already is an old maid To her, death is quite romantic she wears an iron vest Her profession's her religion, her sin is her lifelessness And though her eyes are fixed upon Noah's great rainbow She spends her time peeking into Desolation Row... One of the refreshing characteristics of contemporary global Christianity is the recovery of balance in certain aspects of Christian life and thought. Features subjugated by the dominant Western Tradition re-appear to renew and transform. These include welcome affirmations of the God of life, women, children, 'ordinary people' and their lives and work, and the importance of the heart, creation and material existence, the body of Christ as all of us and the living Spirit of God. This is notably seen in many crosses fashioned in less powerful places which do not dwell lugubriously on death, pain and sin (like so much of Western tradition, not least that shaped by the Reformation era's obsession with mortality and finitude) Instead, in the colours and contours of different contexts, we find crosses becoming signs and places of resurrection: trees of life for and by the marginalised. This does not, of course, do away with what is valuable in such Western Tradition. Yet this shift towards an ethic of natality and flourishing is a great blessing for our world, recovering much that was lost. These few pictures in this slideshow (below) are just some: reflecting the dynamism, hope and down-to-earth realities of Latin America and Indigenous Australia: including a girl's cross; a women's cross; a family cross; the body of Christ today cross; and last supper of many nations.  One of the most misleading sayings in some Christian quarters is that Jesus was born to die. Indeed, so concerned are some to talk about Jesus’ death that they would really like us to put a cross in the nativity scene! Now, of course, the meaning Christians find in the death of Jesus is certainly very important. That is part of why the Easter story is central to Christian Faith. Yet even Good Friday is not ultimately about death. For, as the Bible Society’s lively 2009 campaign expressed it, Jesus. All About Life is the true reality. As Jesus says in John’s Gospel (10.10): ‘I have come that they may have life, and have it to the full’. Death is a part of life and life involves a series of little deaths (losses and griefs) as well as physical death. So Jesus showed us how dying well can be done. Yet this was in service of life, which is the real purpose and invitation of God’s creation of us. For God wants us to live! Christmas, the feast of the birth of Jesus, is therefore not merely a beginning and prelude to Easter. It also witnesses powerfully, in its own right, to the heart of the Christian message. In God in Jesus Christ, we find our fullest life, which is eternal love, right here, right now, and for evermore...  At the heart of the community of Cunnamulla in western Queensland is the town swimming pool. As in many Indigenous, or Indigenous-majority, communities, it plays a central role in fostering community, health, connections and life of various kinds. In Cunnamulla this is certainly notable, not least through the marvellous work of Marianne Johnstone who not only manages the facilities, including the 50 metre olympic-style pool, but wonderfully trains and leads swimming, triathlon and other activities. One of the highlights of our recent diocesan Reconciliation Action Plan initiative in Cunnamulla was therefore the Saturday afternoon swimming gala. The climax of this was the invitation relay race, led by the local mayor Lindsay Godfrey. Our group was encouraged to join in and bishop Cameron Venables and local Anglican Minister Steffan van Munster duly stepped forward to help form a team which came a very creditable third (the winners being an able relay of local Aboriginal young men). It was a powerful symbol of both Cameron and Steffan's ministry among local communities. Instead of simply sitting on the sidelines, or dispensing prizes (though bishop Cameron did that too!), they plunged right into the heart of community life, literally getting soaked in the process. Plunging into the pool is a powerful metaphor for what Christians call the incarnation, the way of Jesus which involves plunging fully into all life has to offer and all of the human condition. Sometimes Christianity, and Christian theology, has been a bit of an, albeit usually kindly and well-intentioned, onlooker activity. Getting wet however is not a real option for genuine ministry and mission. Gustavo Gutierrez, the great Latin American pioneer of liberation theology, reflected that a truly incarnational theology is 'the second act', after the commiitment to life, justice, solidarity with the poor, peace and reconciliation. This is certainly true of the journey of Australian Reconciliation as well as faith development in general. What of my involvement in the pool, you might ask? Well, being a water-challenged person on account of my very British and rural upbringing (far from the unwelcoming cold seas around the UK and at a distance from a pool like Cunnamulla's), I did not myself jump in that pool, although I did offer to join either the running or cycling leg of any similar triathlon. Yet I hope that, in other things I do, I also have the faith to keep plunging in the pool of life. We also have to reflect but active participation is vital. Jump in, as they say in Cunnamulla, the water is wonderful. |

AuthorJo Inkpin is an Anglican priest serving as Minister of Pitt St Uniting Church in Sydney, a trans woman, theologian & justice activist. These are some of my reflections on life, spirit, and the search for peace, justice & sustainable creation. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed