It is a strange thing being English - an extraordinary creatively rich, nuanced, and hybrid identity space but one that has been both so hidden and highjacked in many aspects. Almost every time I’m asked on a form for my country, ‘England’ itself is not even an option - usually the ‘UK’ (not even Britain) is all there is: a political and administrative series of arrangements which have long since lost its way, even now cut adrift from the continent to which it inextricably, if distinctively, belongs. But, seemingly lost and betrayed as it too often is, England remains a resilient and robust reality, full of such diversity and quirkiness of land and people, and with its resistant history of incredible struggles for liberty within and startling surprises of thought and imagination - intimately interconnected with others, on other parts of its island home and beyond: not simply through empire but through hopes and faith that we may nurture a better world, together. And so, beyond the flags and the disturbing crusader elements, may the more generous spirits of England thrive - and may the people and places which formed, and still form, me truly flourish . The recent book by Caroline Lucas, and still more the recent general election results offer some encouragement and inspiration. #anotherenglandispossible

0 Comments

To admit my own mixed family history (including being fair to my mother, a gentle royalist), one of our ancestors actually preached the Restoration sermon for the last King Charles of England in Gloucester Cathedral (I have a copy). What is particularly interesting about him is that he was one of the few pre-Civil War clergy who survived as a parish priest (in the Cotswolds) through all the upheavals of the 1630s-1660s, and (unlike the fabled Vicar of Bray) was clearly held in continuing high esteem - despite being hauled before Presbyterian and Congregationalist inquiries (including the Parliamentary Committee which dismissed errant Ministers) whilst also coming under some attack from ultra-royalists/episcopalians. Maybe having run-ins with church structures, and being attacked from various different quarters, is in my blood?!... It is a bit of a tricky time for some of us right now with the tsunami of royalist outpourings - not least those like me, who, in Australia, also struggle with general Australian assumptions that, being English, we must therefore be monarchists. I’ve been trying to avoid the subject - and especially the media frenzy - but I guess, as I keep being asked about it, I’m trying to find a kind but honest answer. So I hope this doesn’t offend anyone, but other things should also be said...

And for my final song before I leave England before returning to Australia's settler colonialism? Why, something more upbeat: Maggie Holland’s anthem sung by June Tabor: inspired by Christopher Hill’s ’The World Turned Upside Down’, Leon Rosselson’s song, Naomi Michelson’s ‘Sea Green Ribbons’, William Cobbett and other (modern day) English radicals, Jean Giorno’s ‘The Man That Planted Trees’, and the canny Scot Dick Gaughan (‘The first place to be colonised in the British Empire was England’) - about what might be, and what some (in little and subversive ways) still make happen. It also resonates with my recent journey (albeit on a duller December morning) and, of course, my heart… I’ve always so loved this song (see below) - though it always makes me cry - and it, above all, with some others, has accompanied me in the last few weeks. The tender, lyrical and even elegiac, tone fits my mood as I prepare to leave England, maybe never to return, or certainly never with so many of the deep intimate connections of parents, home,and particular place which have so shaped me. Laura Marling wrote this at 18 and says she always feels about 8 years old when she sings it - I know the feeling just in listening . It’s about childhood memories (one in particular) and the ones who created them and about the particularity of place in this extraordinary land which I, like Laura, love so very very much, and from all of which separation is so very poignant. There hasn’t been any literal snow on my winter’s journey but enough in other ways - yet the warmth of love persists, like a beautiful garment in the cold… “You were so smart then In your jacket and coat. My softest red scarf was warming your throat. Winter was on us, At the end of my nose, But I never love England more than when covered in snow.” More splendid creativity at Pitt Street from our worship team 😻 And - sad though I am not to share a first Pitt Street Christmas - I’m so delighted that my brilliant wife (Penny Jones) could preside yesterday. That is the first time for her with our community in Pitt Street - and maybe the first time a female cisgender Anglican priest has presided, with full church authority, in a mainstream Christian denomination in the centre of Sydney. ❤️ I think Maude Royden, the founder of the movement for the ordination of women, will have rejoiced in heaven - especially as Pitt Street gave her a pulpit on her famous visit to Australia years ago (see earlier post here). Hoping one day our good friends in some of the local Anglican and Catholic Churches will share the same blessing - for God’s sake, it was a woman who actually gave birth at Christmas!! It is just lovely to have a female vicar here in Market Rasen at this time and to think of female priests elsewhere in Australia presiding this year (some for the first time - including some of my former students I dearly love and admire). #shininglightinSydney #thankGodfortheUnitingChurch #livingAnglicanism #peacetoall How do you relate to your landscape? At so many turns of my native roads, I’m reminded of the spirits of forebears who trod, tilled, prayed, and sought life and the sacred in these otherwise ‘ordinary’ features of the land. Today this, for example, is ‘just’ a farm. Yet for centuries a double monastery (i.e of women and men) stood here at the foot of the Lincolnshire Wolds during the Middle Ages (from c.1150 to 1538) - one of a number of houses of the Gilbertines (the only completely English monastic order - founded by a Lincolnshire man). Gwaldys, daughter of the last native Prince of Wales, spent her final years here and its priests served our local communities until the Reformation. Subsequently all such land became secularised, with the greatest shift of power and wealth since the Conquest and the coming of the Norman ‘Yoke’, followed by the further deprivations of common land with the enclosures and the ravages of modern industrial agriculture. Of course we can’t simply return, even if we wished, to a sacred medieval understanding of land and creation, but perhaps such remembrances in the land reminds us that there are still alternatives open to us today

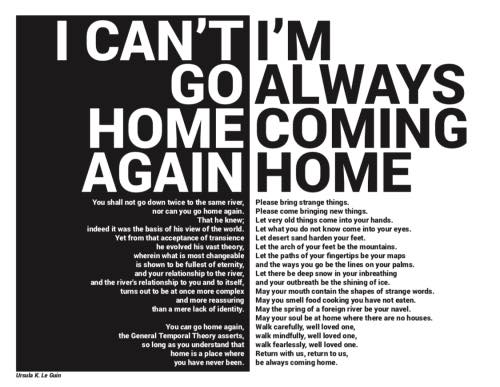

#lincolnshirelandscapes #sacredland I've been reflecting recently on transitions (including the 20th anniversary of our emigration from England in early March), as we traverse our current 'denominational' one - which feels in some ways both like a second emigration and also a deep coming home (on all kinds of levels), as well as other things. As so often, I'm drawn again to one of my great muses, Ursula Le Guin, who so brilliantly explored and celebrated what I might call a 'trans-ing' spirituality - in which binaries are not fixed but intertwine, and in which change and return may be one. These two passages state it so typically passionately and poetically (the first on the lips of Shevek, the central character in 'The Dispossessed' - and the other the blessing, in 'Always Coming Home', given to those who leave their home in the Valley to share with others elsewhere).

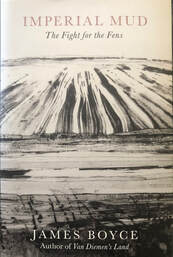

Mind you, when I showed this meme to Penny, she also immediately thought the black and white - with the Going Home theme (Mark Knopfler's great Geordie anthem) - was about Newcastle United! That'll work for me too lol...  Recently I spoke in a sermon about how, as I grew up, I saw the devastation of the English landscape in Lincolnshire, as industrialised ideas of agriculture ripped out hedgerows in the search of short-term profit (see here). A fellow member of Milton Anglicans then shared with me a recent book by her brother, historian and writer, James Boyce. Writing of their ancestral lands, this is entitled Imperial Mud: the Fight for the Fens (Icon Books, London, 2020). It tells of the thousands of years of resistance by the fen peoples of eastern England to the seizing, enclosing, draining, and 'improving' of their lands. It is another part of English history which has buried for too long, a 'home-grown' example of the growth of imperial attitudes and policies which were exported overseas...  The English have traditionally been some of the least inclined to celebrate their own identity with a national day . This is due to a number of historical features, including the way in which my native land has been buried in the complications of British, imperial, and other identities. At best, and excepting the national game of football, there is also something 'un-English', distasteful and concerning about nationalistic enthusiasms and wrapping oneself in a flag. In addition, it opens up the huge question of what kinds of England and Englishness are to be valued and affirmed. On this St George's Day, I am therefore reminded of Billy Bragg's song 'Between the Wars' and a whole host of English inspirations to seek: Not the iron fist but the helping hand Not a land with a wall around it but a faith in one another Not a land of hope and glory but the green field and the factory floor Not skies all dark with bombers but the peace and justice for which the best have always striven With deep thanks and huge pride in/with all others who have come from, sung and celebrated, prayed, written, worked, embodied and partially created 'other' Englands from those which often prevail. |

AuthorJo Inkpin is an Anglican priest serving as Minister of Pitt St Uniting Church in Sydney, a trans woman, theologian & justice activist. These are some of my reflections on life, spirit, and the search for peace, justice & sustainable creation. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed