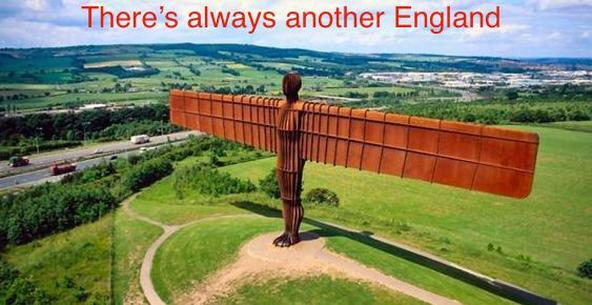

It is a strange thing being English - an extraordinary creatively rich, nuanced, and hybrid identity space but one that has been both so hidden and highjacked in many aspects. Almost every time I’m asked on a form for my country, ‘England’ itself is not even an option - usually the ‘UK’ (not even Britain) is all there is: a political and administrative series of arrangements which have long since lost its way, even now cut adrift from the continent to which it inextricably, if distinctively, belongs. But, seemingly lost and betrayed as it too often is, England remains a resilient and robust reality, full of such diversity and quirkiness of land and people, and with its resistant history of incredible struggles for liberty within and startling surprises of thought and imagination - intimately interconnected with others, on other parts of its island home and beyond: not simply through empire but through hopes and faith that we may nurture a better world, together. And so, beyond the flags and the disturbing crusader elements, may the more generous spirits of England thrive - and may the people and places which formed, and still form, me truly flourish . The recent book by Caroline Lucas, and still more the recent general election results offer some encouragement and inspiration. #anotherenglandispossible

0 Comments

It is a bit of a tricky time for some of us right now with the tsunami of royalist outpourings - not least those like me, who, in Australia, also struggle with general Australian assumptions that, being English, we must therefore be monarchists. I’ve been trying to avoid the subject - and especially the media frenzy - but I guess, as I keep being asked about it, I’m trying to find a kind but honest answer. So I hope this doesn’t offend anyone, but other things should also be said...

Maybe it’s just me, and/or being English (with so many variations of grey & green, and rain, and the landscape romanticism of Turner & Constable et al in my bones and soul) - but I do love the subtleties of grey, green and other colours which sometimes break through to differentiate the otherwise generally wonderful Australian coastal climate (so beautiful but sometimes a little overdoing primary colours and bright starkness?). Rain too is often all or nothing. Today however there is that kind of gentle drizzle which is so healing and refreshing - such that, like a tender massage, it illuminates the natural beauty of Jellurgal (aka Burleigh Heads) and exfoliates it afresh. Sea and sky, beach and bush, meeting and merging with one another in different ways. Why, even the brazen towers of Surfers Paradise are washed in mist and disappear from view!...

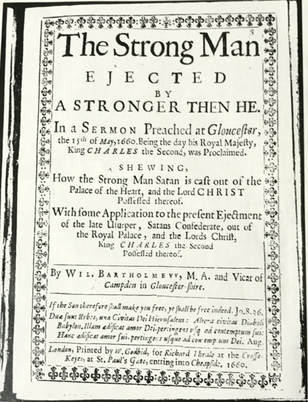

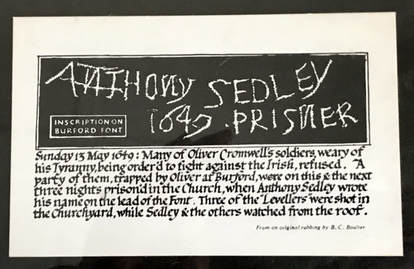

The English have traditionally been some of the least inclined to celebrate their own identity with a national day . This is due to a number of historical features, including the way in which my native land has been buried in the complications of British, imperial, and other identities. At best, and excepting the national game of football, there is also something 'un-English', distasteful and concerning about nationalistic enthusiasms and wrapping oneself in a flag. In addition, it opens up the huge question of what kinds of England and Englishness are to be valued and affirmed. On this St George's Day, I am therefore reminded of Billy Bragg's song 'Between the Wars' and a whole host of English inspirations to seek: Not the iron fist but the helping hand Not a land with a wall around it but a faith in one another Not a land of hope and glory but the green field and the factory floor Not skies all dark with bombers but the peace and justice for which the best have always striven With deep thanks and huge pride in/with all others who have come from, sung and celebrated, prayed, written, worked, embodied and partially created 'other' Englands from those which often prevail.  One of my most fascinating distant ancestors (on my mother's side) was William Bartholomew, who was Vicar of Chipping Campden between 1636 and 1660. As such he lived through many of the epic events of 17th century England: remarkably holding his living from the age of the 'Personal Rule' of Charles 1, even in the upheavals of civil war, the Commonwealth and Protectorate, through to the return of the monarchy. So was he like the fabled 'Vicar of Bray', a by-word for holding on to his ecclesiastical office irrespective of principle? Or was there something more at play in his career? The immediate historical records themselves can be confusing. On the one hand, some have portrayed him as an 'ardent Puritan', perhaps on evidence which suggests he was a major player in the suppression of Dover's Games on the Cotswold downs after 1643. Yet he also appears to have been harassed by the Committee of Plundered Ministers and forced to spend 200 pounds of his own money to avoid trouble. Indeed the memorial in Chipping Campden Church records him as a 'fearless advocate (even in the worst of times) of the Royalist cause.' The latter seems the most likely, as, on Charles II's return from exile, he had the honour of preaching the Restoration sermon in Gloucester Cathedral (see front page pic above right), as well as speedily restoring to his parish the Church of England's Prayer Book which had been proscribed. What then went on in his ministry which enabled his stabilitas through such dramatic changes? The answer needs more research (!), which my beloved late aunt Molly began with my parents a few years ago and which I would love to follow through with at some point soon. My historical hunch however is that, like Jesus' words in the story of Mary and Martha, William Bartholomew effectively continued with 'the one thing necessary': waiting on God in Christ even in the toughest circumstances, continuing to read and expound the Scriptures, and exercising a deeply appreciated 'cure of souls' (earning 'the love and praise and admiration of all', according to his church memorial). As such, his life tells us both something about the complexity of English religion in that tumultuous period (much broader, more localised and even less ideological than simplistic history might assume?) and also that the essence of Christian priesthood (lay or ordained) is not defined by obvious externals (such as the presence or otherwise of episcopacy or authorised liturgy, helpful though they may often be). That may point us to the deepest mystery of all.  From my early childhood, I have always been engaged in exploring what liberty means. I grew up fascinated by history for that reason and it is not for nothing that the pictures over my office desk resonate with some of the mightiest of English struggles for liberty: a copy of the Magna Carta, photographs and records of female suffragists, and, most poignantly of all, a facsimile of the Leveller Anthony Sedley's scrawled protest on the font of Burford Church (see picture to the right). Such epic battles, mixed in as they often were with religious identity and aspiration, both challenge and inspire. They are in parts a record of gruesome hurts but also witness to the Christ-like 'courage to be', to re-imagine, and to 'turn the world upside down' Imagine then my frequent puzzlement and dismay, when some people, in comfortable places, speak about religious liberty as merely the right to hold and publicise curious opinions and practices or to protect privilege. Of course I would not wish to deny others the first of those things. Yet liberty is so much more...  Forget the UPF anti-Muslim banner stunt at the MCG. Australians are generally much more civilised than most in dealing with religious and cultural diversity. This afternoon in Toowoomba was a case in point. Our Toowoomba Garden City Mosque is in serious need of re-building, following the fire almost a year ago. What to do? Why not, said our local Muslim community, ask the neighbours round for a cup of tea to talk it through? - and not with the slick presentation and glossy leaflet plans some groups might effect. So it was that, as chair of the Toowoomba Goodwill Committee, I also joined a goodly gathering of people from the immediate vicinity of the mosque for a meet and greet and disperse any heat. After all, I am an ethnically English Australian, and what is more English than a cup of tea (especially when you can be the vicar popping round)? This kind of holy humdrum action is typical of community life in Toowoomba and further afield. Sadly, such widespread generous connections rarely get the attention the hotheads do. It is certainly very much representative of Muslim-wider community relationships in our city here. In one sense, it is simply just another step in the journey. Yet every stage matters, not least when there may be concerns about new local construction and the footprint it may provide. In this case, the plan is to remove the old de-mountable and extend the mosque (previously an old church building), widen the roof space but retaining the existing height limits, add three metres to the front to provide space for genuinely appropriate toliets and washing facilities, and put in a mezzanine level to enable women's space. It was a delight to see and be part of the warm and genial conversations (even over parking), and to hear of the generosity of other locals, like one of our (other than Muslim) city lawyers who has provided legal advice towards the rebuilding for free. All of us enjoyed our time together and look forward to the next steps which will bring fresh community as well as physical environment pride to us all.  As an English Australian Christian, ANZAC Day has been, and remains, somewhat enigmatic. I appreciate, and am sometimes deeply moved, by aspects of it. Yet it often feels a little alien, particularly in its more recent forms: adding, as they do, extra nationalistic and even militaristic overtones to a developed myth which is itself somewhat sub-Christian, and at times even anti-Christian (when, that is, it over-exalts the very elements of blood-sacrifice and trajectories of human violence which Christ's work transfigures and ends). Generally therefore, I tend simply to let ANZAC commemorations pass by, except when I am forced to confront them: such as at the SCG one day at an AFL match, where the invasion of the pitch by a military parade and ritual was a powerful reminder of the sometimes problematic relationship between sport and violence (indeed I wondered what it would take, and what reaction there would be, to a peace march and peace ritual in the same space in a similar manner). As a proud and happy Australian citizen, I believe strongly in the right of my fellow Australians to hold and practice ideas and behaviours different from my own. I also rejoice in the virtues and outstanding stories of courage, resistance and mutual support in the ANZAC myth and I pray that these may indeed flourish in positive ways in our lives and world today. However I still often feel somewhat distanced. Are there, I wonder, ways forward to a more inclusive commemoration?...  It ill behoves an Englishman, and an Australian citizen, to advise Scots how to vote on their future. How exciting it is however that this debate is happening, both for the future of England (and Wales and Northern Ireland) as well as that of Scotland. Which ever way the vote goes, Britain as a whole will never be quite the same - thank God - as the Scots reflect on what it means to look to a post-Imperial future, and, hopefully, encourage the rest of the British to do likewise. For it is good that the British PM David Cameron tells us that he has a heart, at least for some things which have been good about the United Kingdom's structure. Even better though if he were to have a real heart for those things which are at the core of this debate: the longing of people everywhere to be taken seriously for who they truly are; to claim freedom and full responsibility for their lives, their land, and all that lives within it; and to seek a people's vision based on values of genuine democracy, justice and care for all, including free and fair partnership with the rest of the world. Generations of heartlessness by the English elites towards the poor and marginalised throughout Britain (not least to the Celtic so-called 'fringe'), have led us to this pass. A 'United Kingdom' which is still essentially a Union of ancient Crowns can never be enough. With the Scots, the English (the Welsh and maybe many Irish too) also deserve a forward-looking 'Community of Peoples'. My own Scottish friends remain divided on how that may best be immediately furthered: is full independence a help or a hindrance? I sympathise with them in their dilemma. Yet whatever the outcome, they agree that it at least begins to engage Britain's contemporary, post-imperial, identity. So may the spirit of my greatest Scottish hero, James Keir Hardie, thus prevail... |

AuthorJo Inkpin is an Anglican priest serving as Minister of Pitt St Uniting Church in Sydney, a trans woman, theologian & justice activist. These are some of my reflections on life, spirit, and the search for peace, justice & sustainable creation. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed