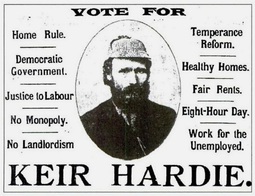

It ill behoves an Englishman, and an Australian citizen, to advise Scots how to vote on their future. How exciting it is however that this debate is happening, both for the future of England (and Wales and Northern Ireland) as well as that of Scotland. Which ever way the vote goes, Britain as a whole will never be quite the same - thank God - as the Scots reflect on what it means to look to a post-Imperial future, and, hopefully, encourage the rest of the British to do likewise. For it is good that the British PM David Cameron tells us that he has a heart, at least for some things which have been good about the United Kingdom's structure. Even better though if he were to have a real heart for those things which are at the core of this debate: the longing of people everywhere to be taken seriously for who they truly are; to claim freedom and full responsibility for their lives, their land, and all that lives within it; and to seek a people's vision based on values of genuine democracy, justice and care for all, including free and fair partnership with the rest of the world. Generations of heartlessness by the English elites towards the poor and marginalised throughout Britain (not least to the Celtic so-called 'fringe'), have led us to this pass. A 'United Kingdom' which is still essentially a Union of ancient Crowns can never be enough. With the Scots, the English (the Welsh and maybe many Irish too) also deserve a forward-looking 'Community of Peoples'. My own Scottish friends remain divided on how that may best be immediately furthered: is full independence a help or a hindrance? I sympathise with them in their dilemma. Yet whatever the outcome, they agree that it at least begins to engage Britain's contemporary, post-imperial, identity. So may the spirit of my greatest Scottish hero, James Keir Hardie, thus prevail...  Certainly, if you are looking for a model for a people's politician for Britain as a whole, then it is hard to look far beyond Keir Hardie. Born and bred in the poverty of late 19th century Lanarkshire and Glasgow, Hardie first broke the subjugating British political mould by standing as an independent Labour candidate for the British Parliament in Mid-Lanarkshire in 1888. He was first elected however for an English constituency (West Ham South) in 1892 and then for a Welsh constituency (Merthyr Tydfil and Aberdare) in 1900. Always, as a fervent Christian, Keir Hardie's concern was never parochial, but first and foremost for the recognition, freedom and empowerment of the poor and marginalised, of whatever national or other background. This is what drove him on in his struggles for miners, trades union organisation and labour representation, in his partnership with the women's movement as the leading parliamentary and christian feminist of his day, and into deeply committed internationalism and peace campaigning, up to, and (at the cost of an early death) into, the First World War itself. No wonder Scottish Labour today is still fighting over his soul and where he would stand on independence. He was certainly in favour of home rule, part of his original electoral platform. Is this the same however as the current Scottish 'Yes' independent version of self-determination? Hardie's vision, like that of his master Jesus, was so much bigger than nationalism, even that of a very democratic socialist character. He sought a community - even a communion - of all peoples, united in love, peace and justice, strong in their unique identities, but intimately connected to the greater kingdom of God. So how would he view today's 'Yes' campaign and political model for the future? Is this part of, or a distraction, from his wider vision? It is hard to see Keir Hardie being happy with the feeble posturing of David Miliband, his successor today as British Labour leader, or with many of the Labour 'Tories in red ties' working for a 'No' vote. He would however be rejoicing to see the spate of concessions being forced from the 'No' camp, offering greater powers to Scotland whatever the vote's outcome, and offering possible precedents even for England too. For this is a challenge but also an opportunity for England - my England, Keir Hardie's England, Billy Bragg's England - 'not the land of the iron fist but of the helping hand', as Billy put it (albeit with an unusual lack of gender inclusion) in his song "Between the Wars': For theirs is a land with a wall around it And mine is a faith in my fellow man Theirs is a land of hope and glory Mine is the green field and the factory floor Theirs are the skies all dark with bombers And mine is the peace we know Between the wars Call up the craftsmen Bring me the draftsmen Build me a path from cradle to grave And I'll give my consent To any government That does not deny a man a living wage That is the crunch, I feel, for the Scots. Which kind of a land do we who are British believe in? Scottish, English, or Welsh, or Northern Irish, where do we place our political energy and give our consent? How best can our shared British vision of fair lands, and our radical legacy, be expressed today? For an English person, there are genuine concerns about the prospect of Scottish independence. especially for someone like me who hails from England's north-east. After all, politically, socially and in many ways culturally, the north-east has much more in common with Scotland than it has with London. I strongly resonate with the Scottish aspiration to be more like the Nordic countries in their commitment to robust social democracy, international human rights and independent peacemaking values. The loss of intelligent, grounded, compassionate Scottish voices in the Westminster Parliament is also not a happy prospect Yet the Scots have no monopoly of British radicalism. Perhaps, if it comes to it, as Billy Bragg argues, Scottish independence might indeed finally start to inspire the English Debate. Perhaps, whatever happens, we might start to re-value and re-embody the so-very English vision of the Levellers and Chartists, and the imagination, intelligence and compassion of Blake, Cobbett, Orwell and so many more Perhaps we might at least start to ask why the English people, cannot also have our own fuller rights and responsibilities. If it is good enough for the Scots, and to a lesser extent the Welsh and even the Northern Irish, to at least have some devolution, how come London and the English elites still run English lives? Is it time for the English to be set free to work out what it is to be English today, not just buried as an identity beneath the broader concept of Britain? Whatever the Scottish referendum outcome, we will always all still be British, but maybe we will have started to work out more clearly what are the specific gifts of our distinct but interlinking identities, for the benefit of ourselves, each other and the wider world. For that wider world most certainly stills needs Britain, especially in its full and rich diversity. It still delights in Scottish, Welsh, and English, capacity for creativity, tolerance and adventure, and (at our best) our humour, self-deprecation and connectivity with others. It does not need an imperial anachronism. Perhaps Billy Bragg is partly right: Take down the Union Jack, it clashes with the sunset And put it in the attic with the emperors old clothes When did it fall apart? Sometime in the 80s When the Great and the Good gave way to the greedy and the mean Britain isn’t cool you know, its really not that great It's not a proper country, it doesn’t even have a patron saint It's just an economic union that’s passed its sell-by date Perhaps Billy Bragg is also partly wrong. Even allowing for artistic licence, Britain is certainly so much more than just an economic union or a single land entity. That is at the heart of the Scottish debate. Yet Britain, as a fully 'United Kingdom' or otherwise, cannot stay pickled in aspic. My final thoughts at this time on the 'Scottish question' are historical and ecclesiastical. How is it that British Anglicans have been able to get along just fine for years and years in independent Churches - the Episcopal Church of Scotland, Church of England and Church of Wales - yet still maintain, and develop throughout the world, powerful, though not always uncontested, lively bonds of deep communion? Is there something to learn here? I recall too how it was the Scots who finally sparked the 17th century English Revolution, refusing, rightly, to accept the imposition of a new Prayer Book upon them by the tyrannical English (though supposedly also Scottish) King Charles 1. Charles, 'the Man of Blood', cared more for his imperial power than the needs and consent of his peoples, and had almost continually avoided the Westminster Parliament's limited oversight of his reign. Only the need for money to fight the Scots' spirit of independence forced him into consulting even the English elite. The rest, as they say, is history, as that 'Scottish question' led to English conflict and new English ideas of freedom, community and consent: about how to be a people, how to govern oneself and how to include and to relate to others in a vision of a new world for all. It was painful, as all transitions are. Thanks be to God that David Cameron and his camp are not Charles 1, Oliver Cromwell, or their ilk! We can do better in our own age. Yet perhaps, in that sense, we should be viewing this current debate as not the end of a sunset but the beginning of a sunrise? Whatever the outcome, Keir Hardie might be smiling.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJo Inkpin is an Anglican priest serving as Minister of Pitt St Uniting Church in Sydney, a trans woman, theologian & justice activist. These are some of my reflections on life, spirit, and the search for peace, justice & sustainable creation. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed