As I sat in a doctor’s waiting room recently, I saw the words be. here. now. prominently displayed. How appropriate I thought. For a doctor’s waiting room is typically made up of people who would rather not be there at that moment. Indeed, in such a liminal space, we are usually full of thoughts, hurts and fears which do not make it easy for us to be present. We may be occupied with concerns about the past, such as the mishaps or illness which has brought us to that moment. We may be absorbed with worries and anticipations about the future. We may be full both of regrets and forebodings. However, whilst very human, none of this really take us very far. In the face of the, sometimes profound, dislocation of time, space and meaning caused by dis-ease, we need to be able to acknowledge and express these things. Yet ultimately they are not the deepest truth of our lives at the moment and they do not provide pathways to healing. When time, space, and meaning seem to be collapsing around and within us, knowing that we are still ultimately OK, right where we are, is vital. Terrible pain and suffering can of course certainly make it almost impossibly hard even to breathe, never mind acknowledge this reality. However what some of us call 'the divine embrace' is still always there for us, right here and now. Can we trust, and, even in death, let that eternal presence heal and re-create us?...

0 Comments

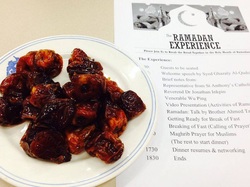

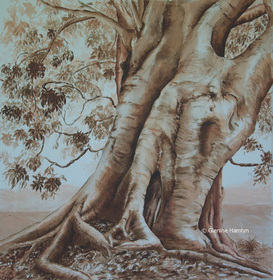

Wednesday evening was a delightful example of the nature of interfaith peace and harmony life in Toowoomba. Not only were members of our Muslim community wonderfully warm and welcoming but all kinds of people were present from across our diverse wider community. And it all took place on Christian premises, at St Anthony's Catholic Church in Harristown. Jesus, I think, was smiling: all God's children together, sharing 'table fellowship', sharing faith and food, life and laughter together. Sharing the evening Iftar (breaking of the fast) with others has become a very valuable and enjoyable part of Australian life. Each year, many Australians of other faith and none happily experience the generous invitation of their Muslim neighbours to join in this important part of the Muslim year and to grow in deeper understanding and love together. Thanks, in Toowoomba, go out especially to the coordinators of the Islamic Interfaith and Multicultural Committee. For, as a spiritual gift, hospitality is one of the most vital contributions anyone can make to peace and harmony. It is certainly one aspect of Ramadan which enriches others, though not the only one. Ramadan, like daily prayer in Islam, is also a gift to recall the rest of us to attentiveness, mindfulness and the presence of God. It is a binding force for community, here and across the world. It helps release our society from the compulsions to consume and blunt our senses with material things alone. Indeed, only when we know how to fast (in various ways) do we really feast properly. 'Let us cherish fasting', Athanasius, the great early Christian bishop and theologian said, 'for fasting is the great safeguard along with prayer and almsgiving. They deliver human beings from death.... (for) to fast is to banquet with angels.' Delivered from the destructive powers of self, we can then be more generous and hospitable towards others. Hospitality is certainly a central theme of Anglican inter-faith and cross-cultural endeavour. As the helpful international Anglican document Generous Love puts it: As God both pours out his life into the world and remains undiminished in the heart of the Trinity, so our mission is both a being sent and an abiding. These two poles of embassy and hospitality, a movement ‘going out’ and a presence ‘welcoming in’, are indivisible and mutually complementary, and our mission practice includes both. This kind of hospitality is therefore an expression of the very nature of the God whom we approach in different ways. Such true hospitality is not about losing, but expressing, our integrity and convictions. Rather, we in turn can then receive the gifts of others, which can speak powerfully of the welcoming generosity at the heart of God. For , as Generous Love reflects: through sharing hospitality we are pointed again to a central theme of the Gospel which we can easily forget; we are re-evangelised through a gracious encounter with other people. Transformed by God, we become paradoxically both deeply centred and radically open, for our centre is self-giving love. Faith is not then based on human work, such as particular belief or practice, but on grace. In all the great spiritual traditions, fasting and feasting are gateways and expressions of this.  Do you see the wood or the trees? Only a few seem capable of seeing both. My friend, and former ecumenical colleague, Glenine Hamlyn is one of these special people. She possess both a compassionate grasp of the world's crises (not for nothing has she worked in development issues) and also an acute sensitivity to the immediate and the specific. This is revealed in her art, something to which she is currently able to give more time and focus. The picture to the left (now hanging on a wall in my home) is a wonderful example. In the midst of busy Brisbane, this one Moreton Bay fig captured her attention and in it amazing detail is revealed. So many people pass by daily without really seeing it, just as we pass by so much without really seeing. An artist can thus draw us back to proper attention, not so that we lose the wood, but so that it comes alive with the intricate complexity which is true wholeness. Mary Oliver's beautiful poem 'The Summer Day' encapsulates so much of the real challenge of a spiritual life. As she writes elsewhere, in 'Wild Geese': 'You do not have to be good./ You do not have to walk on your knees/ for a hundred miles through the desert, repenting./ You only have to let the soft animal of your body love what it loves.' How hard it often is for us to believe, and, still more, trust and live this. We have so often allowed ideas of exile, death, sin and punishment to predominate in our psyches, rather than welcome, life, grace and forgiveness, which are so much more central and eternal. All too often even so-called rebels, rakes and critics have protested, and lived, a false dichotomy between the material and spiritual, the now and beyond, the human and divine. Mary Oliver instead calls us to attention, to the mystery of the everyday and everywhen, and to living of life in all its fullness.

The final words of the poem 'The Summer Day' have also been ringing round my consciousness for the last two and a half months: 'Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?' Perhaps this blog and website is but one small step for me in responding to that challenge, an expression of my own call to attention, and to expression of the mystery and meaning I glimpse and seek to live. Maybe my good soul-friend Graham is right, self-effacement can be a frustrating buried treasure. Graham introduced me to Mary Oliver's work and a wild and precious life certainly demands more. That phrase also came alive for me this weekend as I pondered two men whose funerals I had been asked to lead. One died only a year older than I am now. Like Bob Dylan's admission about Lenny Bruce, 'maybe he had some problems, maybe some things that he couldn’t work out', but he was more spiritually awake than many. Bruce Laurie was somewhat wild in several senses, but he was also precious and he lived life to the full. The other man was a Toowoomba country man of the old school but of a high intellectual calibre. His late wife Olwen was a weekly communicant in our Anglican parish but Reid was more complex, not just more shrewd but more sparing, in his spiritual commitments: perhaps his very unpretentiousness kept him from expressing publicly, or aloud, the deepest longings and experiences of his heart. He was full of life and virtues however, which shine on in his grieving children. He paid attention and seized life's opportunities and challenges, passionately but graciously. Now he rides his wild horses beyond the western sunset and into a new summer's day. He, like Bruce, would have loved to have argued and agreed with Mary Oliver's poet-forerunner Horace, drowning a beer together on the verandah (or in Bruce's case perhaps something stronger in a nightclub): Carpe Diem. May they rest in peace and rise in glory, and may we attend and let the soft animal of our bodies love what they love. |

AuthorJo Inkpin is an Anglican priest serving as Minister of Pitt St Uniting Church in Sydney, a trans woman, theologian & justice activist. These are some of my reflections on life, spirit, and the search for peace, justice & sustainable creation. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed