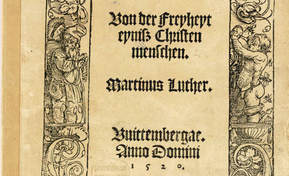

In the heat of current political issues, is it possible to find a healing ethic of religious freedom? Might a fresh look at Christian tradition help us with this? The ideological use of notions of 'religious freedom' is certainly hardly new. Judaeo-Christian history is riddled with it and their consequences. Jesus himself was famously condemned, according to John 's Gospel (11.50). since it was argued that it was better for one person to die than for the nation to be destroyed (allegedly). Other faith expressions and Christian 'heretics' have met comparable fates. Meanwhile, in many places, Jews and Christians have experienced, and continue to experience, harassment, persecution, and even outright destruction. Yet the Jewish and Christian traditions are also founded on expansive ideas of liberty, grounded in the very being of God in God-self, and on liberative myths and symbols such as Exodus from slavery, return from Exile, deliverance from sin and evil, and the in-breaking and embodiment of God's reign of justice, peace and love. These have empowered, and continue, to empower people to achieve freedom across the world. Not for nothing then did Martin Luther call his seminal work 'On Christian Freedom'. Its use highlights three typical trajectories western society has explored in relation to 'religious freedom'. Its central message however points us deeper... The paradox of freedom and service

Luther is certainly not a figure whom conservatives can easily adopt in the search for legislative protections. His ideas of religious freedom were indeed attractive to so many because they were so powerfully subversive of inherited religious privileges. Yet they are also not simply transferable to progressive or radical forms. Rather there is a profound paradox at the heart of God's freedom. For Luther’s central claim was the double statement: that ‘a Christian is the most free lord of all, and subject to none: (and that) a Christian is the most dutiful servant of all, subject to all.’ (1 - see footnotes below) This is both a paraphrase of St Paul’s words in 1 Corinthians 9.19 and a working out of Luther’s animating principle of justification by faith through grace, embodied in the priesthood of all believers. Through God’s righteousness, empowered by the Word of God and living in Christ, human beings are set free. ‘This’, Luther wrote, ‘gives the liberty of the Christian; no dangers can really harm them, no sorrows utterly overwhelm them, for they are always accompanied by the Christ to whom they are united by faith.’ (2) The radical trajectory This dynamic conception of freedom, and the use Luther made of it to attack the religious establishment of his day, understandably warmed the hearts of radicals in his own day and afterwards. From the firebrand theological and political revolutionary Thomas Muentzer and other radical Reformers, through to the development of socialism and the East German communist state, 'religious freedom' has thus sometimes been put to radical ideological use. Indeed Karl Marx himself commented that: Germany’s revolutionary past is theoretical, it is the Reformation… the revolution then began in the brain of the monk. . . if Protestantism was not the true solution it was at least the true setting of the problem.‘ (3) Luther himself, under pressure for the sheer survival of himself and his message, quickly distanced himself from both political and more thorough-going ecclesiastical revolutions. Against the Rioting Hordes of Peasants was his main rejoinder, produced in May 1525, and harshened by some publishers into Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants. As the title suggests, this condemned the peasant rebellions: for violating their oaths of loyalty to the state, committing crimes contrary to their faith, and for blasphemy in using Christ’s name to support their acts. For with this came Luther’s strong attachment to princely authority as appointed by God. The conservative trajectory A second ideological trajectory for the use of 'religious freedom' can thus also be developed out of Luther's thinking. This is a conservative approach which was led, from the first, by Roman Catholic leaders and scholars. Key elements of this include the precedent and encouragement which - when unexpurgated or separated from other theological themes - Luther’s ideas of freedom give, not only to undermining papal authority, but to the dissolution of all authorities, save that, arguably, of the individual conscience. In Luther’s early work moreover, the emphasis he gave to the primacy of justification by faith through grace left his thought vulnerable to attack as an antinominian weakening of productive human works and law. Undoubtedly, as in other areas of controversy, Luther did not help himself with his highly polemical and combative style: ‘There is an undying struggle between the lawyers and theologians’, he argued. ‘The law is a fine, beautiful guide, so long as she keeps to the nuptial couch. If she ascends another bed, and tries to control theology, she becomes no better than a prostitute. Law must doff her cap in the presence of theology.’ (4) For Luther it seems, law is therefore to be treated with suspicion, albeit for principally theological rather than political reasons, although the very real threats and power of Roman Catholic canon law and its secular political backers also bulked large for him. The consequence however, picked up by more conservative critics ever since, is a tendency to false distinctions between law and grace and law and gospel, by driving to an extreme some Augustinian and Pauline theological themes.(5) The result can be especially problematic when combined with aspects of Luther’s 'two kingdoms' approach to the relationship of Church and State. How are the claims of religious freedom and order to be developed in tension with the realities of political freedom and order? The liberal trajectory In contradistinction to both radical and conservative interpretations of Luther’s doctrine of freedom, a third approach is a liberal one. This takes liberty as a supreme value and goal of human life and society. In fact, its true foundations are not to be found in the ‘magisterial’ Reformations. Instead they are in the Enlightenment and in those religious precursors, such as the 16th and 17th century Anabaptists, spiritualists and other dissenters, whom Luther and his immediate followers rigorously opposed. Such an approach also extends religious toleration, or even full affirmation, to others of faith, such as Muslims and Jews whom Luther himself at best despised and sometimes excoriated. Notwithstanding this, such a line of interpretation also takes Luther as a pioneer for his commitment to conscience. (6) For nineteenth century Liberal Protestantism adopted this theme of liberty of conscience as a central tenet. As the founder of the Tubingen School of Theology, F.C.Baur put it: ‘what is referred to as liberty of faith and conscience and the unalienable right that the Reformation bestowed on (hu)mankind, is only a popular expression for an intellectual autonomy. It is identical to the principle of subjectivity, an absolute self-consciousness of human thinking liberated from an authoritarian faith. Protestantism is the principle of subjective freedom, of liberty of faith and conscience – of autonomy, in contrast to the heteronomy of the Catholic concept of church.’ (7) Such an understanding still pervades much liberal Protestant and progressive religious thought today. Like the other lines of interpretation, it is not without value, yet it is also a distortion of Luther himself and insufficient as a contribution to sticky questions of freedom and religion and their inter-relationship today. So, how might Luther still help us? The 'conscience of freedom' To help tease out how Luther’s paradoxical doctrine of freedom may still inform Christians and wider society today, it is necessary to return to Luther’s principal concern: God and theology (God-talk). For, in doing so, we can distinguish between Luther’s bondage to his own context and prejudices, and his enduring value. For, in freeing Luther from our needs and preconceptions, we set free fresh perspectives on our lives and work, whether we be theologians, lawyers, or anything else. In his article Martin Luther: on Jurisprudence – Freedom, Conscience, Law, published three decades ago, Heinrich Stoller helped point us in this more fruitful direction. Tracing the historical development of the use of Luther’s terminology, he affirmed the need for us to avoid posing ‘two polar alternatives – pious obedience to the state or religious anarchism’.(8) Both are indeed part of the possible developmental trajectories of Luther’s thought, but they are distortions which seek to escape Luther’s paradox. Opposition to, or advocacy of, freedom of conscience for ourselves, or for others, is not the heart of Luther’s thought. Rather it is what Stoller identified as the concept of ‘the conscience of freedom’.(9) Moreover, this idea was not an essentially subjective, individualist, interpretation. It rested on the objective measure of Scripture and active participation in the life of both Church and world. Whilst we may be moved by his own stand for conscience, it is not, in other words, to Luther's personal and political practice that we should look for guidance but to his theological and ethical methods. For Luther’s primary concern is the mercy and sovereignty of God which is the basis for our freedom. As Scholler put it, conscience for Luther was not the application of the law or knowledge, as it had been for Thomas Aquinas and medieval jurists: ‘Rather it was the mystical sphere in which a gigantic struggle for the redemption of the soul took place.’(10) So for Luther, ‘freedom of conscience was not as important as the conscience of freedom, a freedom from the condemning law and the wrath of God which raged in the conscience’,(11) freedom given through justification by faith through grace. In other words, the Christian Gospel is not to be reduced to battles over law, politics and culture. Christians, Luther affirms, are indeed to engage with them. For we live in the two kingdoms, of God and of the world, simultaneously. Yet we are not to be bound by the world and its thinking. There is a perspective we are given, and a freedom to love and serve, which transcends them. Holding the two halves of the paradox of freedom together As we approach heated issues of freedom and religion today, I often wonder both whether Christians frequently lose this focus and society as a whole fails to recognise its value. For too often we are trapped together into arguments over freedom of conscience without appreciating the conscience of freedom. Instead, the two halves of Luther’s paradox of freedom are crucial and interdependent: ‘a Christian is the most free lord of all, and subject to none: (and) a Christian is the most dutiful servant of all, subject to all.’ The inner freedom given by grace is the foundation to our ‘lordship’. Yet it follows that freedom must include appropriate law, for this is part of how service can be exercised and Christian freedom made subject to all. For, in Luther’s formulation, liberty, of a Christian at least, is not a means to self-affirmation or a protective device, but a dynamic, active, reality, which seeks the good of others: what he called ‘the freest of works’.(12) Today, we might take this up and perhaps recast Luther’s remarks about law: instead, for example, of asking law to doff its cap, theology and Christian ethics might be better employed assisting others, including lawyers, to serve with that same spirit of combined freedom and responsibility. Religious freedom as an act of grace: freeing us from self-concern Shorn of his polemic, and his own political and cultural assumptions, Luther’s paradoxical doctrine of freedom still cuts through much of which passes for religious thinking about liberty today. For as George Forrell put it: ‘to modern men and women… God does not justify; he needs justification… The sequence attributed to Luther that Christian ethics starts with faith which is active in love, has been completely reversed. Today we tend to use God as a traditional fiction to support the many causes in which we have much more confidence than in God. We do believe in our liberty but not as a gift of God, dependent every moment on God's grace, but as a right that makes us into autonomous beings for whom faith in God is an option. This is part of our religious liberty as are atheism, witchcraft, and belief in unidentified flying objects.’(13) In contrast, Luther affirmed freedom fundamentally not as human work but a gift of grace. In Forrell’s words: ‘it is an empowering gift because it enables the recipient to be freed from self‑concern, the obsession with his or her own interest, for the real needs of others. Christian ethics in the more restricted sense is only possible on the basis of this liberation. There are all kinds of good works that people can do… works of the law which may contribute to the earthly welfare of human beings. But the life that makes a woman or a man into a Christ to others is only possible for those who have been made one with him and thus can say with Paul: "It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me" (Gal 2:20).’(14) Luther's 'Golden Rule of Rights' - and the responsibility not to be bigots To conclude, the outflowing of a fuller understanding of the conscience of freedom in our current context would therefore be a less defensive and more humble approach to the claims and threat of others. Such a relationship between civic liberty and rights can also be illuminated by Luther’s treatise in 1523 Temporal Authority: To What Extent It Should Be Obeyed. The Christian, Luther affirmed, is ‘under obligation to serve and assist’ the government for the benefit of others. For ‘love constrains’ Christians to use their liberty to engage in civic life, not for their own advantage but for the good of others.(15) Luther’s own ‘Golden Rule of Rights’ (15) thus follows: ‘For nature teaches—as does love—that I should do as I would be done by [Luke 6:31]. Therefore, I cannot strip another of his possessions, no matter how clear a right I have, so long as I am unwilling myself to be stripped of my goods. Rather, just as I would that another, in such circumstances, relinquish his right in my favour, even so should I relinquish my rights.’ (16) How, one wonders, does that sit with, for example, Christian attitudes in the debates such as marriage equality? That of course ties into much larger discussions, and wider issues, about how religious freedom and law live positively together. Yet, perhaps George Brandis was right, in relation to exploration of Section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act, to affirm that everyone ‘has a right to be a bigot’. That might be a part of our, sometimes misplaced, and fallen, nature, in our lordship of creation. Yet, in the light of Luther’s paradox and conscience of freedom, we also, as loving servants, have the responsibility not to be bigots. (this is an edited version of my longer paper 'Loving and Limiting Liberty: the continuing challenges of Luther’s paradoxical doctrine of freedom', given at the Luther Colloquium at University of Southern Queensland, 31 October 2017) [1] Martin Luther, “The Freedom of a Christian,” in Luther’s Works, ed. H. J. Grimm, Philadelphia: Muhlenberg Press, 1957, pp.343–44. [2] Ibid, p.55 [3] Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Law, in Marx and Engels Collected Works. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 175-87.1844 p.182 [4] The Life of Luther, Written by Himself, ed. Jules M.Michelet, translated by William Hazlitt, London, 1846 p.301 - available online here [5] see further for example, Massimo La Torre, Constitutionalism and Legal Reasoning: A New Paradigm for the Concept of Law Springer, Dordrecht 2007, ch 3 p.91 [6] See also for example, among other contemporary figures valuing Luther’s stand for conscience Michael Kirby ‘Thomas More, Martin Luther and Judiciary Today’, address to the St Thomas More Society, Auckland, New Zealand [7] F.C.Baur, Die Epochen der Kirchlichen Geschittsschreibung 257 (1852), quoted in Heinrich Scholler, Martin Luther on Jurisprudence—Freedom, Conscience, Law, 15 Val. U. L. Re. 265 (1981). Available here [8] Ibid p.281 [9] Ibid [10] Ibid p.270 [11] Ibid p.271 [12] Luther’s Works, ed. H. J. Grimm (Philadelphia: Muhlenberg Press, 1957), 31:360 [13] ‘Luther and Liberty’, op.cit [14] ibid. [15) Luther’s Works, ed. H. J. Grimm (Philadelphia: Muhlenberg Press, 1957), 45:98, quoted in ‘Liberty and Rights in Light of the Reformation and Enlightenment Traditions’ by S.Ashmore & D. van Voorhuis, in Issues in Christian Education, online here [16] Ibid [17] Luther’s Works, ed. H. J. Grimm, 45:127-128

1 Comment

|

AuthorJo Inkpin is an Anglican priest serving as Minister of Pitt St Uniting Church in Sydney, a trans woman, theologian & justice activist. These are some of my reflections on life, spirit, and the search for peace, justice & sustainable creation. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed