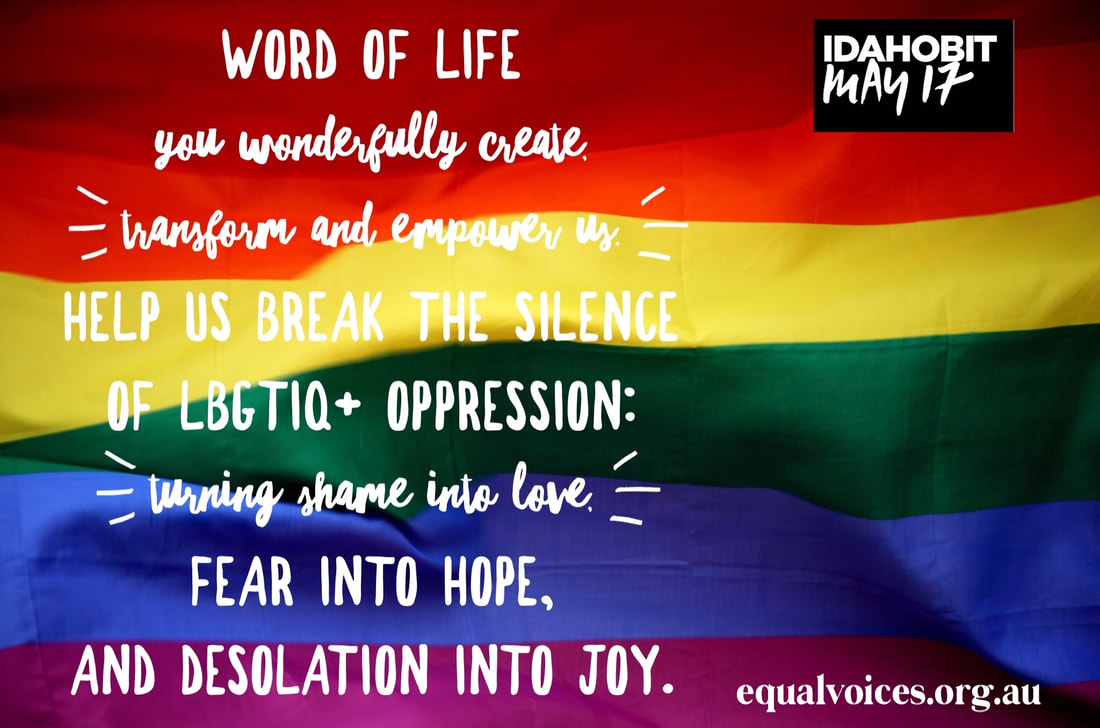

I first formally joined the (UK) Lesbian and Gay Christian Movement in 1990, the year that the World Health Organisation removed homosexuality from the Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, and IDAHOBIT - the International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia, Interphobia & Transphobia - began. May 17 (IDAHOBIT) marks the anniversary of that significant WHO change, and since then considerable advances have been made by LGBTIQ people across the world and in many key sectors of life. The original gay and lesbian focus has also been widened and deepened to acknowledge the rich diversity of human sexuality and gender: IDAHOBIT thus started as IDAHO, without bisexual, intersex and transgender engagement, just as the Lesbian and Gay Christian Movement, to which I still belong, has broadened as One Body One Faith. The need for IDAHOBIT is still nonetheless massively apparent, particularly in many countries of the world. Under the cover of the COVID-19 crisis, some, such as Hungary and Poland, are also moving backwards in respect and affirmation. In countries such as Australia, understanding and support of bisexual, intersex and transgender people still lags behind progress for gay and lesbian people. As the International Day reaches 30 years old however, it is also a time for appropriate celebration of remarkable positive developments in so many places and areas of life. When, and how, however will Churches, and other religious groups grow up to their own mature humanity, 'to the measure of the full stature of Christ' (as Ephesians 4.13 puts it)?... religion - the last refuge of the scoundrel?

As a priest, transgender person, and long time advocate for life-giving change, it has been depressing to experience the slowness of positive response by Churches to the movements of growth in relation to sexuality and gender. As official bodies, they have typically not only been resistant to the light of LGBTIQ experience and scientific knowledge - seemingly, as Jesus put it, lacking 'eyes to see and ears to hear' the ever clearer demands of love, justice and humanity. They have even become leaders in reaction. Sadly this has included continued refusal to honour their own sexually and gender diverse members, whose gifts are so vital for their own survival and growth. Indeed, in this respect it seems at times that, to adapt Dr Johnson's phrase, religion has become 'the last refuge of the scoundrel'. Thus, even within parts of comparatively 'mainstream' religious bodies in society, things are able to be said, and done, about LGBTIQ people which would not now be countenanced in so many other quarters. The current moves to enshrine the 'right' to religious discrimination are symptomatic both of attitudes and approaches stuck in a previous century, and of regarding sexually and gender diverse people as if we were a virus to be avoided, contained, and, if possible, eliminated. stuck in the 20th century? Church leaders and others frequently tell us that more scholarship needs to be done and/or we need more time to discuss the matters involved. Yet reviewing recently my own not inextensive library of Christian LGBTIQ books and other publications, I was struck by how long LGBTIQ people of faith, and key allies, have been shedding light and campaigning for change. Not only have the so-called 'clobber texts' been examined ad nauseam, but, much more importantly, for decades religious scholars have highlighted vital gifts and perspectives which sexually and gender diverse people bring to faith and life. Yet, like rabbits in headlights, otherwise well-meaning Churches remain typically frozen to the spot in the face of the death-bearing vehicle of fundamentalist reaction. Actions, and even limited engagements with the real issues, continue to be postponed. For many Anglicans across the world for example, it seems as if we are perpetually stuck in the 1990s, perhaps in 1998 to be more precise, as if the Lambeth Conference of that year was the limits of possibility. reactionary advance The Churches' situation has sometimes worsened from 1990. To continue the Anglican example, I thus vividly remember a bishop from the USA coming to speak in my, then English, parish before the 1998 Lambeth Conference. He spoke confidently of the likelihood of a global Anglican process of reception for LGBTIQ people, similar to that achieved, not without much time and tears, in the reception of women's ministry and leadership in the Church. Such North American and progressive hubris was however devastatingly exposed at the 1998 Lambeth Conference, as a Resolution (1.10) was passed, vigorously affirming that the Communion: in view of the teaching of Scripture, upholds faithfulness in marriage between a man and a woman in lifelong union, and believes that abstinence is right for those who are not called to marriage. To be fair to the Lambeth Conference bishops, the Resolution also: calls on all our people to minister pastorally and sensitively to all irrespective of sexual orientation and to condemn irrational fear of homosexuals. That latter part however has had far less attention than the first. US and other progressive bishops were, as they saw it, 'ambushed' in 1998 by an alliance of conservative Western Anglicans with growing numbers, seeking to flex their muscles, from the Global South. Such forces have consolidated since in the powerful Global Anglican Future Conference (GAFCON). The effects have been increasingly destructive to reasoned discussion, Church unity, partnerships and mission with others beyond the Church, and, critically, participation of LGBTIQ people. Thankfully, some Churches have moved forward, including parts of the Anglican Communion. Yet even some positive developments have been hedged about with reservations. Thus, for example, the 2018 decision of the Uniting Church in Australia to allow the celebration of marriage equality is greatly to be welcomed. Yet it came with a reinforcement of 'the rights of ministers and congregations who remain committed to the traditional understanding of marriage as exclusively between a man and a woman' (see further Uniting Church Past President Andrew Dutton's nuanced explanation of this in relation to UCA 'diversity' here). Hence the Uniting Church's strong stand against other enduring sins such as sexism and racism is not fully replicated when it comes to issues of sexuality and gender identity. Of historic ecclesial bodies in Australia, only the Society of Friends (Quakers) have joined the Metropolitan Community Church (MCC), and some smaller independent churches, in full LGBTIQ affirmation as Churches for the 21st century. silence, concealment and abuse The negative consequences of refusing to engage the gifts and faith experience of LGBTIQ people have been, and remain, staggering. This is nothing new, so Churches cannot plead ignorance. Back in 1990, for example, in the year IDAHOBIT began, renowned spiritual writer and Anglican priest Kenneth Leech wrote the following words which are sadly still true today. Commenting on the already well-established need for pastoral reorientation, recognised by the WHO and IDAHOBIT that year, he said (in Care and Conflict: Leaves from a pastoral notebook (DLT) p.17): In many ways, however, the church is still caught in the position which prevailed in society as a whole before the reforming legislation and the emergence of the gay liberation movement. Hence the terrible atmosphere of dishonesty and doublespeak which makes serious discussion of this issue virtually impossible in many church circles. Rowan Williams, later Archbishop of Canterbury, made a similar point, two years before IDAHOBIT began, in his fine Jubilee Group contribution Speaking God's Name. In words I know are so true, for so long to the cost of my own gender identity, he rightly identified, within Churches: We have helped to build a climate in which concealment is rewarded - while at the same time conniving in the hysteria of the gutter press, and effectively giving into their hands as victims all those who do not manage successful concealment. This year's IDAHOBIT call for Breaking the Silence is therefore particularly signifcant for Churches. The Australian Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Abuse painfully exposed the appalling record of Churches in failing in the past to put into place, and administer, protocols and awareness training to avoid abuses and affirm vulnerable members of its body. Without similar attention to LGBTIQ needs, Churches will however persist in further abuse and failures to affirm. For, as we have learned in the COVID-19 crisis, without attending to reason, considered policy, determined will, and communal participation, we cannot avoid unnecessary destruction, never mind nurture a healthier and more flourishing society together. homo/bi/inter/trans phobia as a virus in the Body of Christ One way of looking at the religious problems LGBTIQ Christians face is to see it as a manifestation of a pervasive virus within the Body of Christ. Certainly today, as down the centuries, LGBTIQ people are treated in many religious circles as pathological. Of course responses differ to this viral diagnosis, some of which are unconscious. Even where they are not fully affirming, not all religious spaces seek to exterminate, expel, or exorcise. Yet wariness and suspicion, if not worse, are endemic in most religious groups. Ecclesial social and theological distancing is encouraged, if not enforced. Ecclesial social isolation and quarantining of 'queer' people and ideas of faith is widespread. Sexually and gender diverse people and our 'infections' are still considered necessary to be closeted and denied fresh air and expression. In my own Australian Anglican Church, this was powerfully symbolised for me in the production last year of a national Doctrine Commission document on marriage. Not one fully affirming openly sexually and/or gender diverse person was engaged as a contributor, and our three decades and much more (!) of rich faith, relationship, and theological experience were almost completely ignored (see further my critique here). It was a clear example of how little has changed since 1990, and how the key principle of 'nothing about without us' is typically ignored by Churches for fear of infectious results. Elsewhere in the world, such exclusions are not always so obvious. The Church of England's Living in Love and Faith process for example does display a commitment to genuine seriousness in theological breadth and depth, and, importantly, to involving LGBTIQ Christians. Yet the experience of notable transgender and intersex contributors, leading to their dismayed withdrawal, has not been happy - see further, for example, the Revd Dr Christina Beardsley's incisive article Why I left the BIshops' sexuality project. As IDAHOBIT challenges us, if we are serious about affirming our common humanity, we need to delve much deeper and take much greater care to engage those whose lives and bodies are on the line, valuing them fully. does religion and the religious deficit matter to LGBTIQ people? Now, as some secularists volunteer, one answer to the religious deficit on healthy sexuality and gender diversity might be to leave religion aside altogether. Believe me, that is something to which many of us who have striven hard for change have sometimes been tempted! However my sense is that is not only to fall in line with the manifestly false fundamentalist assertion that God and religion are fixed. It may be difficult for Churches to respond quickly to the pace of change today but history amply shows that Christianity, like other great religious traditions, has always adapted to changing contexts. More importantly, for all LGBTIQ people, and serious allies, to quit religion is to hand its power over to others. This is because, in a deep sense, the religious battle is vital to everyone. For legal and other external progress has also been hard to attain but is always vulnerable to being rolled back if wider inner attitudes and values are not transformed. Unless the spiritual virus of homo/bi/inter/trans phobia is addressed, we will all suffer. Whilst it can still be uncomfortable at times to be a person of faith in some LGBTIQ spaces, it is therefore encouraging to see the active inclusion of sexually and gender diverse people of faith in more and more contemporary LGBTIQ settings and campaigns. Indeed, it is hard to see how the campaign against unhealthy proposed religious discrimination laws can be fully successful without the involvement of LGBTIQ people of faith who are both themselves at greatest risk and who can share vital alternative perspectives to those loudly asserted by religious bigotry. Perhaps some of us may need to change our particular form of religious allegiance but the invitation is to create something more life-giving.. ending 'russian roulette' The experience of LGBTIQ people in entering most Church spaces has helpfully been characterised as 'playing russian roulette'. For even where churches appear, or assert themselves, to be 'welcoming', or even 'inclusive', we can never be entirely sure that a bullet may not be fired at us, from the pulpit, or elsewhere, in 'loving Christian fellowship'. That is why Equal Voices (the Australian national network of LGBTIQ Christians and allies) is so clear that 'welcoming' and 'including' are insufficient. Individual congregations or other religious entities need to be at least seeking to be (fully) 'affirming' in order for us to recommend churches as safe places. In this we require strong evidence of resolutions and active measures of education and practical change. Sometimes this seems hard to some sympathetic Church leaders. Some Anglican bishops have said to me for example that they believe more of their churches are LGBTIQ positive than Equal Voices will allow. The realities tend to be otherwise. An empathetic priest or section of a church community is not enough. LGBTIQ people have come painfully to learn that we must trust the experience of our own community. As with theological, pastoral and other initiatives towards us by the wider Church, we, in God. are the real experts on our own lives and bodies, our safety and our flourishing. Where then do we go in breaking the silence, transforming the phobic virus, and ending russian roulette within religious circles? Three aspects - better connecting, communicating and creating - seem increasingly necessary to me... connecting Firstly, there is an outstanding need for better connections both between LGBTIQ Christians themselves, and also between LGBTIQ Christians and serious allies, Church leaders and structures, and the much wider LGBTIQ community. The principle of divide and rule, or be divided and suffer, is central. The foundation of Equal Voices in Australia was a vital step in this. For, just in Australia, there are some wonderful denominational groups in existence, such as the affirming Catholic network Acceptance and Uniting Network. Yet, without also working closely together, LGBTIQ Christians are always likely to be frustrated by internal denominational forces and being overly 'family selfish' focused. Such networks also need to be well resourced and sustainable. This is far from the case in Australia, where Equal Voices and other groups work on a shoestring and where more LGBTIQ people and allies need to offer financial and other active support. The usually greatly under-recognised strains on LGBTIQ people working in the religious sector can be extraordinary and burn out is a common feature among those who are most active. Better connecting with others is also vital. Partnerships with key, genuinely serious LGBTIQ supportive, church leaders and public figures has been, for example, a key feature of successful and outstanding work by the Ozanne Foundation in the UK. In Australia, closer and more effective collaborations with other civil society bodies and LGBTIQ leading agencies, such as Equality Australia, need to be nurtured. LGBTIQ Christian groups such as the Brave Network in Victoria, and the survivors of SOGICE (Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Change Efforts) are positive models of such development. In each case, whilst eshewing the frequently proferred pathways of false unity and cheap grace, they display a fresh clarity and openness to working with others constructively. communicating Secondly, breaking the silence, dispelling the homo/bi/nter/trans phobic 'religious' virus, and transforming ecclesial russian roulette will be greatly furthered by improved and more imaginative communications. This begins by withdrawing further from the stale and deeply debilitating battles over 'clobber texts' and the framing of issues by hostile or resistant Christians. As I seek to say to leaders and opinion shapers in my own Christian tradition, we need to take a leaf out of the way in which healthy schools treat children expressing the need for gender transition. Best practice here involves person-centred care and expression, drawing in carers and professionals as appropriate, and working out ways forward. It does not involve going straight to the most trans-suspicious members of the school community and asking them for their involvement, and even direction, in process and outcomes. Yes, such people may need to be duly informed at a later stage, but not until substantial safe conversations and ways forward have been established. LGBTIQ Christians also need assistance from others in opening up space for our stories and faith insights to be expressed. Media has often been unhelpful in this respect in the past, particularly when it has reported on controversial issues, such as religious discrimination, by reference mainly to the same highly conservative Church leaders, not drawing on a wider spectrum of opinion from across the country, not least LGBTIQ Christians themselves. creating Thirdly, and most challengingly, greater creativity is essential if Churches are to rise to the opportunties for new life offered by IDAHOBIT to enter the 21st century and foster fullness of life for all. 'Business as usual' will simply not work. Reactionaries, such as GAFCON in the Anglican Communion, know this only too well. They therefore constantly push the envelope of established order and break ranks and the boundaries of protocol and received expectations. This is also part of the effective, though highly bounded, creativity of conservative Evangelical religion. In contrast, far too much LGBTIQ Christian and allies' expression is too polite, too little, or too late. Allies need to be more like accomplices, not mere cheer-squad members who quickly evaporate for other interests or when things become tough. LGBTIQ Christians also need to find ways to deepen our courage and creativity. For a major block to religious progress is our own inability to come out, speak out and act out. As someone who took so many years to live fully into my own gender identity in a religious space, I know how hard that is. For priests and pastors, and others with personal stakes in established institutional religion, we risk our livelihoods, families, relationships and futures, Yet until more of us stand up and say 'no more' we have little chance of change. Only then will leaders in religious spaces begin to realise that healthy 'risk management' of our issues demands engagement and affirmation, not continual evasion and denial. IDAHOBIT and Church beyond 30 Across all areas of life, the current COVID-19 crisis offers us opportunities to move forward, if we would take them. We can choose simply to try to 'snap back' to 'business as usual', or we can seek a much better, much healthier, society and set of embodied religious values, than we had before. As we mark the 30th anniversary of IDAHOBIT this year, my sense is that many Churches will prefer to resume their inherited patterns, saturated with homo/bi/trans phobic assumptions and practices. Perhaps the alternatives just seem too hard. As a result, they will remain troubled, and incapacitated by their inability to grow up into mature humanity and engage with the divine gifts of diverse sexual and gender identities offered to them. As the years pass they will then increasingly become ever more stubborn and shrill. Already their children and grandchildren have been giving them a wide berth. Even 'good children', like myself, who have sought ways to stay with them, are now finding the struggle hard to maintain. That pathway of refusing to face relationship and reason can only lead to futures of desperate denial, depression and destruction. Or the Churches can choose to turn around (repent) and face the wonder of our rich human variety, opening up their hearts, minds, and structures to those they suppress and deny. LGBTIQ people of faith will not be disappearing but we will not be waiting around for ever. We, if not our Churches, will not waste all our years. We are not a virus but an antidote and a source of new life. We exist in the 21st century and we have living to do.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJo Inkpin is an Anglican priest serving as Minister of Pitt St Uniting Church in Sydney, a trans woman, theologian & justice activist. These are some of my reflections on life, spirit, and the search for peace, justice & sustainable creation. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed